You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

2020 College Free Speech Rankings

A large survey about free speech and expression on college campuses found that students, especially those in the political minority at an institution, are censoring or editing what they say and are uncomfortable and reluctant to challenge peers and professors on controversial topics.

Sixty percent of students have at one point felt they couldn’t express an opinion on campus because they feared how other students, professors or college administrators would respond, according to a survey report published Tuesday by the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, or FIRE, a campus civil liberties watchdog group, and RealClearEducation, an online news service. The survey of 19,969 undergraduate students from 55 colleges and universities was administered from April to May by College Pulse, a research company.

Sean Stevens, senior research fellow in polling and analytics for FIRE, said the survey is the largest the organization has conducted and possibly the largest survey ever conducted about freedom of speech on campus. Similar recent surveys have had sample sizes of about 3,000 to 5,000 students.

The report digs into whether students feel they can openly engage in specific scenarios, such as when a controversial speaker comes to campus or how comfortable they are speaking about race, abortion or other “controversial” topics in the classroom, Stevens said.

Lara Schwartz, director of American University’s Project on Civil Discourse and an expert on campus free speech, said the survey provides a picture of students’ perceptions and indicates that students largely see their college as generally supportive of free speech.

When students were asked if college administrators “make it clear to students that free speech is protected” on campus, 70 percent answered yes, the report said. Fifty-seven percent of students also said that if there were a “controversy over offensive speech” on campus, their administrators would be more likely to defend the speaker’s First Amendment rights, compared to 41 percent who said that administrators were more likely to punish the speaker in this situation, according to the report.

Schwartz cited these findings as a sign that students generally feel their specific campuses are creating a positive environment for free speech. They may be self-censoring because they feel they will be judged by others on the campus or are considering possible social consequences for what they say, rather than the colleges themselves "making some speech harder," she said.

“Students accurately believe that their schools will protect free expression. That’s a good thing,” Schwartz said.

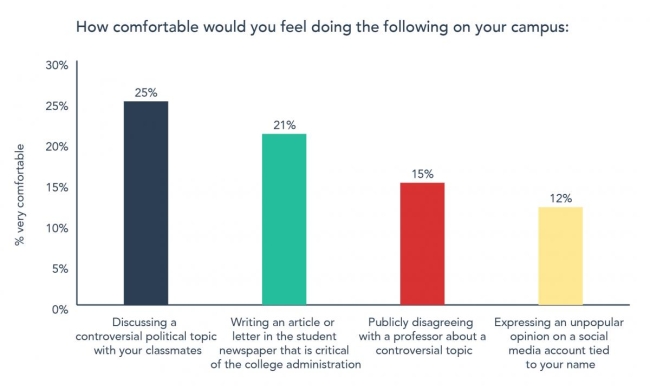

Over all, students were more likely to feel comfortable discussing controversial political topics with peers and less comfortable “publicly disagreeing” with a professor about such topics, the report said. One-quarter of students said they felt “very” comfortable discussing the topics with classmates, and 42 percent felt “somewhat” comfortable. One-quarter of students said that they felt "somewhat" uncomfortable with these discussions and 9 percent were "very" uncomfortable.

When asked how they would feel openly disagreeing with their professor, only 15 percent of students said they would be “very” comfortable and 30 percent said “somewhat” comfortable, the report said. Thirty-three percent said they would feel "somewhat" uncomfortable and 22 percent said they were "very" uncomfortable with the idea of disagreeing openly with a professor about a controversial topic.

Robert Shibley, executive director of FIRE, noted that report's goal is to provide prospective students and their parents with a tool to measure the political and cultural climate of individual college campuses and help them gauge whether an institution is friendly to free speech and open debate. FIRE ranked the 55 colleges where responses were collected, including all eight Ivy League institutions, using a zero-to-100 scale that is based on students' survey responses and the colleges' policies for protecting and restricting free speech.

The University of Chicago ranked first over all, and Shibley praised the university’s “reputation for defending free speech.” The low rankings of large public state institutions, such as the University of Texas at Austin, ranked 54, and Louisiana State University, ranked 53, were “a surprise,” he said.

"Obviously where campuses stand on free speech is not going to be as significant to students compared to how much money they have to spend," or U.S. News & World Report rankings of the institutions, Shibley said, "but it should play a part if students are deciding between different schools, or if students have opinions that are likely to be silenced on a given campus and if they want to engage in activism."

FIRE also developed an average “liberal” and “conservative” score for the colleges based on survey responses from students who are more left- or right-leaning, the report said. Students could use the information to select a college that is more in line with their own ideology or belief, but Shibley said the hope is they evaluate their choices based on how tolerant a specific college would be of all viewpoints.

While the rankings take into account how students with specific ideologies feel about whether their campuses are open to various views, Stevens said an open-ended question at the end of the survey found that many students had personal reasons why they might be self-censoring. Some students are worried that speaking up about controversial topics or sharing an unpopular opinion in class will affect their grade and do not want to offend their professors or classmates, he said. Some also expressed fear of administrative retaliation or mentioned reluctance to criticize their college or university because they are employed by the institution, he said.

Schwartz noted that during her own research for the University of California National Center for Free Speech and Civic Engagement, students also listed dependence on campus jobs and scholarships as a reason to censor or edit their own speech.

Stevens said there were “mirror image comments” from students on opposite sides of the political aisle, who felt uncomfortable speaking up about particular issues because they knew they were in a political minority. Students that identified as Democrats on campuses where they were outnumbered by Republicans felt similarly to students who self-identified as Republicans in an environment with mostly Democratic students, he said.

“One of the most common things that comes up is politics and perceptions,” Stevens said. “Whether they’re liberal or conservative, if they’re in a minority, they’re less likely to speak up. That’s a pretty prominent theme across the board with the political disagreements.”

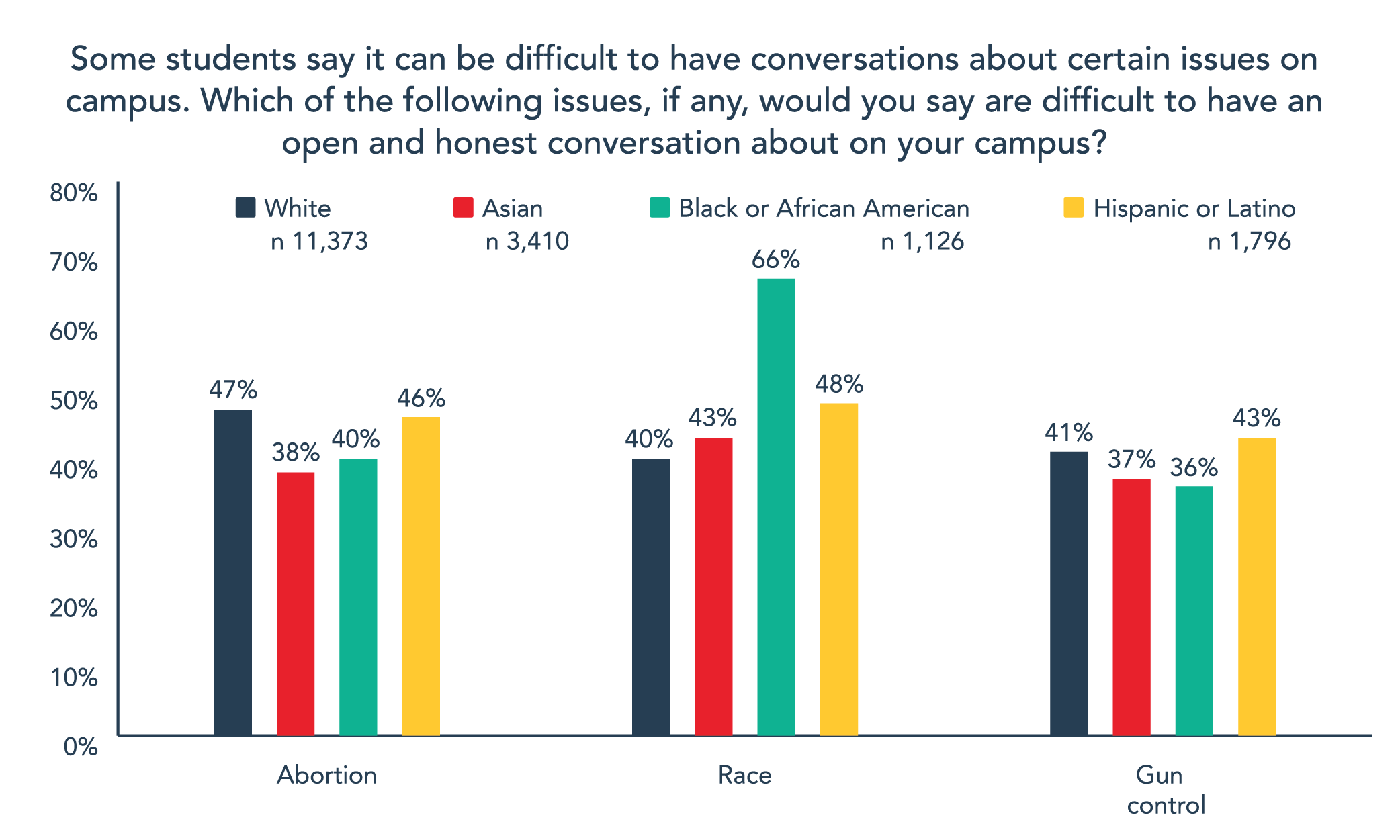

Stevens said he wasn’t surprised to see abortion and race as the top two topics that students found “difficult to have an open and honest conversation about” on their campus. About 44 percent of students surveyed selected these topics; gun control and transgender issues followed close behind, according to the report. Stevens said Black students were more likely to face difficulties having “open and honest” discussions about race than all other ethnic groups.

Sixty-six percent of Black students identified race as a challenging topic versus 43 percent of students over all, the report said. In written responses, students explained that they might be the only Black person in the classroom and it can be uncomfortable to bring up issues of race, or that they are also expected to speak for all Black people during discussions on race, Stevens said.

Schwartz said such problems could come into play when Black students who may have attended predominantly Black high schools enroll at predominantly white institutions. This “culture shock” can also be the same for white students who may experience significantly more diversity on campus than they did in their high schools, and also make it uncomfortable for them to speak about race, she said. Schwartz said these scenarios can also significantly influence how students feel speaking about political issues.

“A lot of the focus that we might give on this self-editing question is much more complex than what’s happening on a college campus,” Schwartz said. Many students “are coming from homogenous communities and are coming into much more heterogeneous communities in college … People are very unused to being in a community where they’re a minority viewpoint.”

Schwartz said that the report's findings could be used to illustrate to faculty members and administrators why more work needs to be done educating students to be more tolerant of a range of ideas and on how to effectively have “tough conversations.”

There should also be more opportunities for students to learn how to make mistakes and apologize when having controversial discussions, otherwise students see certain speech as being "allowed" or "not allowed," she said.

Shibley said that professors have a responsibility to "set the standard of free inquiry" in the classroom.

"It ought to be place where people have their beliefs challenged, make different arguments where that’s appropriate and understand the strengths and weaknesses on both sides," Shibley said. "That’s what makes a meaningful class."