You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Departments have been having quiet conversations since the start of the pandemic about how graduate admissions will be affected: Will there be money to support new graduate students in COVID-19-reduced budgets? Even if there is money, is it ethical to admit new Ph.D. students amid widespread faculty hiring freezes?

With the arrival of the 2021 graduate admissions cycle, these conversations are now becoming public. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s history department, for example, recently said that it is accepting no new graduate students for fall 2021.

The English department at the University of Chicago made a similar decision, with a twist: the program will admit only those graduate students who plan to work in Black studies.

“For the 2020-2021 graduate admissions cycle, the University of Chicago English Department is accepting only applicants interested in working in and with Black Studies,” the program said in a statement on its website. “We understand Black Studies to be a capacious intellectual project that spans a variety of methodological approaches, fields, geographical areas, languages and time periods.”

The statement says that Black lives matter, as do George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and “thousands of others named and unnamed who have been subject to police violence.” It also says that English as a discipline “has a long history of providing aesthetic rationalizations for colonization, exploitation, extraction and anti-Blackness,” and it is “responsible for developing hierarchies of cultural production that have contributed directly to social and systemic determinations of whose lives matter and why.”

Disciplinary progress has been made on this front, Chicago’s English faculty wrote. Yet there is “still much to do as a discipline and as a department to build a more inclusive and equitable field for describing, studying and teaching the relationship between aesthetics, representation, inequality and power.”

The university said in a separate statement that “like many graduate programs around the country,” English at Chicago “can accept a limited number of Ph.D. graduate students in the 2020-21 application season due to the COVID-19 pandemic and limited employment opportunities for English Ph.D.s.”

Chicago currently has 77 Ph.D. students studying a wide variety of subfields, and the department is admitting five additional Ph.D. students for 2021.

The department’s faculty “saw a need for additional scholarship in Black studies, and decided to focus doctoral admissions this year on prospective Ph.D. students with an interest in working in and with Black Studies,” Chicago said.

The work of “undoing persistent, recalcitrant anti-Blackness in our discipline and in our institutions must be the collective responsibility of all faculty, here and elsewhere,” according to the English department's statement. “In support of this aim, we have been expanding our range of research and teaching through recent hiring, mentorship and admissions initiatives that have enriched our department with a number of Black scholars and scholars of color who are innovating in the study of the global contours of anti-Blackness and in the equally global project of Black freedom.”

In closing, the English professors acknowledged “the university's and our field's complicated history with the South Side” of Chicago, where the campus is located. While the university serves as a “vehicle of intellectual and economic opportunity for some” in the surrounding community, it remains a “site of exclusion and violence for others.”

Kudos and Backlash

The department’s decision has been lauded by those who view it as putting action behind academe’s recent pro-Black Lives Matter rhetoric. The decision also has been criticized by those who see it as exclusionary, nondiverse or out of alignment with Chicago’s relatively purist position statement on campus speech, known as the Chicago Principles.

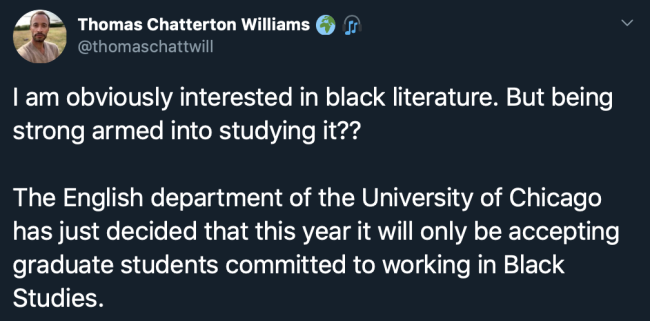

Author Thomas Chatterton Williams, who has written about race and identity, said on Twitter, “I am obviously interested in black literature. But being strong armed into studying it??” Political activist Ayaan Hirsi Ali tweeted, "This is all too idiotic. Most of us don't know whether to laugh or cry. By the logic of their creed, wouldn't English be the oppressor's language?"

Others have defended the program in conversations on social media, saying that prioritizing Black studies for reasons of pedagogy and scholarship at this time does not mean hiring only Black scholars or only teaching Black studies. Indeed, many scholars of Black studies are not Black, and Chicago's English faculty remains overwhelmingly white, with a variety of specialties. Some supporters have pointed out that the academy is historically exclusionary to Black scholars and that students, and especially underrepresented students, benefit from learning from a diverse set of mentors. And some have said that anyone who doesn't like Chicago's policy is free to apply anywhere else.

Maud Ellmann, chair and Randy L. and Melvin R. Berlin Professor of the Development of the Novel in English at Chicago, said the department decided to “target admissions only in specific areas because we were instructed that we could admit only five Ph.D. students in the current cycle, although we expected about 750 applications,” as the program’s application rate tends to rise in times of “crisis.”

Instead of looking at a less-than-1-percent admission rate, the department decided to focus on Black studies, which has become one of its “new strengths owing to some brilliant recent hires,” Ellmann said.

“While some of these new faculty members have already gained international recognition for their scholarship,” she added, “others are just starting their careers, and we wanted graduate students interested in Black studies to know that they would receive the highest standard of mentorship in our program.” Beyond that, “We also wanted to produce a cohesive cohort of students working together towards compatible goals.”

As for some of the criticism, Ellmann said, “Far from precluding other subject areas, the department plans to target other areas in future years. This is a practice already well-established in the sciences, and under current circumstances it makes sense for us to focus on specific fields instead of trying to cover the whole range of English studies with a minimal intake of students.”

Ellmann said the department has “no intention of strong-arming students into one subject area or another, though like all departments we encourage students to make the best of our strengths.”

Students take many courses in different subject areas as part of the Ph.D. program, “and some change their initial dissertation plans as a result,” she added. “We encourage students to experiment and find their own direction under careful supervision from our faculty, all of whom take part in the admissions process.”

Chicago is not alone investing in diversity even in a time of financial insecurity across academe. Syracuse University, for one, recently said that it will proceed with a planned diverse faculty hiring initiative amid a more general, COVID-19-related hiring freeze.

LoVonda Reed, associate provost at Syracuse, said in a statement that due to the “uncertainties ushered in by the COVID-19 pandemic, we paused faculty hiring in the spring and summer.” The university is now reviewing hiring priorities with “the expectation that we will restart faculty hiring,” but the diversity opportunity hiring initiative has already been restarted, she added.

As with other departments at Chicago, that university said its English faculty members “will decide which areas of scholarship they wish to focus on for Ph.D. admissions in future years.”

Suzanne Ortega, president of the Council of Graduate Schools, said some schools have made the decision to limit or suspend recruitment in specific doctoral programs for next fall “for reasons that generally relate to the pandemic.”

Spring 2020’s unplanned shutdown affected degree timelines for graduate students already enrolled, she said, “and their programs are prioritizing support to ensure current students are able to complete their degrees.” That means offering “an additional semester or two of funding” in many cases, Ortega continued, so program directors have “opted to shift their budget for 2021 recruitment to continued support for the doctoral students already in the program.”

That’s what’s happening in history at Chapel Hill. The department said in a statement this week that it will not accept applications for the 2021 admissions cycle.

“In order to ensure that the department has resources to adequately support its educational mission during the COVID-19 pandemic and after years of state budget cuts, we will hold off on bringing new entrants to the program until 2022,” Chapel Hill’s history department said. “The decision to eliminate a cohort of future graduate students was not an easy one, but we have decided that the most responsible course of action is to prioritize those who are already in our program.”

Chicago, as a relatively well-off private institution, isn’t facing the same financial pressures as Chapel Hill. It also has a new funding model for graduate students that involves admitting new students, with full funding, only as current ones finish their degrees. But COVID-19 has left no institution financially unscathed, and it’s pushed an already bleak faculty job market into blight. Doctoral program admissions caps historically have been a third rail for programs, but the coronavirus has made them touchable, at least for the moment.