You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

ISTOCK.COM/Lorado

As colleges bring students back to campuses for the fall semester, questions are increasingly being raised about what it would take to send them home or revert to online instruction in the event of an outbreak of COVID-19.

New York governor Andrew M. Cuomo drew a red line for New York State colleges on Thursday, announcing, "If colleges have 100 cases or if the number of cases equal 5 percent of their population or more, they must go to remote learning for two weeks, at which time we will reassess the situation."

In other states without such guidance, faculty and students are increasingly calling on colleges to release information on the criteria they’re using to decide whether and when a shift from in-person to remote operations is necessary.

Relatively few colleges have published specific numerical benchmarks they’re using to determine when a surge in COVID-19 cases might trigger a closure, although an increasing number are posting general information about the criteria they are considering. Common criteria include metrics related to COVID case numbers and positive test rates, local hospital admission rates, and occupancy rates of rooms set aside for quarantine and isolation.

One college that has published specific metrics is the University of Wyoming. In draft metrics last updated Aug. 11, the university lists a number of specific benchmarks that would trigger an automatic pause of in-person operations while administrators assess the situation. The benchmarks include a one-day increase of 20 or more new cases relative to a rolling seven-day average, a daily positive test rate exceeding 5 percent, or a fatality in the UW population.

Berea College, a small private college in Kentucky with a focus on serving low-income students, has also published criteria that would cause it to consider closing the campus, including reaching 80 percent of quarantine and isolation capacity or having 10 employees sick at any one time.

"I was glad to have those metrics out there," says Berea's president, Lyle Roelofs. "Faculty and students are paying close attention, they’re asking me quite regularly how are we doing compared to the metrics. It's good to have something solid out there for people to depend on rather than just saying, ‘We administrators have good judgment and we’ll know when to think about this.’ I think that wouldn’t play as well with our community.”

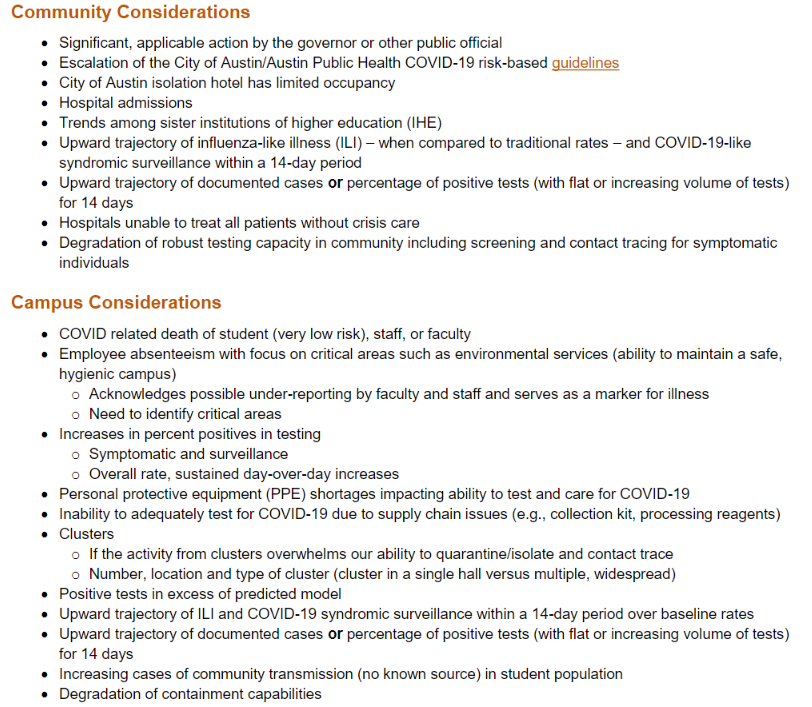

Some other colleges are publishing lists of the various criteria they would take into account in any closing decision without identifying specific numbers that would trigger closure. The University of Texas at Austin has published a detailed list (at left) of community and campus-level considerations that are being used as “decision triggers” for closing or partially closing. Other colleges that have published such lists include Eastern Michigan University, Liberty University and the University of Kansas.

Some other colleges are publishing lists of the various criteria they would take into account in any closing decision without identifying specific numbers that would trigger closure. The University of Texas at Austin has published a detailed list (at left) of community and campus-level considerations that are being used as “decision triggers” for closing or partially closing. Other colleges that have published such lists include Eastern Michigan University, Liberty University and the University of Kansas.

Kansas’s chancellor, Douglas A. Girod, emphasized that the criteria would be evaluated holistically by the university’s Pandemic Medical Advisory Team.

“In other words,” Girod wrote, “there is no single indicator, single circumstance, ‘magic number’ or ‘trigger’ that will alone lead us to change the state of campus operations.”

The University of Wisconsin at Madison similarly says it will not rely on a single metric.

"There is no single criterion that will push us to make a decision about reversing or scaling down our plans," Madison's chancellor, Rebecca Blank, wrote in a message Wednesday. "We are monitoring several quantitative and qualitative factors -- these include the percentage of people testing positive and capacity in our on-campus isolation and quarantine spaces, as well as broader community measures such as the county’s percentage of people testing positive and the capacity of our health care system. We will also continue to receive advice from infectious disease experts here on campus as they help us monitor what is happening. We have developed a number of contingency plans that allow us to adjust our operations to a fast-moving situation."

Some students and faculty are asking for specific numbers. Cornell University’s provost, Michael Kotlikoff, recently responded to such calls on the campus in Ithaca, N.Y. He told members of Cornell’s University Assembly last week that 250 new cases in a week would be “a trigger to say consider shut down.” (Kotlikoff made the comments before Governor Cuomo's announcement on Thursday setting a lower threshold of 100 cases. The university said in a statement the same day that it will “work in close consultation with Tompkins County Health Department and in strict accordance with all New York state guidelines.”)

The argument for publishing metrics comes down to issues of transparency and accountability.

Andrew M. Schocket, a professor of history and American culture studies at Bowling Green State University, argues that the publication of metrics “would require college and university leaders to confront the potential mortal toll of learning and explicitly weigh the risks that they are asking their students, faculty and staff, along with community members, to bear.”

“While they may rue the lack of flexibility such an approach would entail, that is the point: setting these conditions ahead of time will mitigate how, once the semester is underway, their decision making will inevitably be clouded,” Schocket wrote in an opinion piece for Inside Higher Ed.

Chris Marsicano, assistant professor of the practice in educational studies at Davidson College in North Carolina, notes, however, the downsides of reducing administrators' room to maneuver by putting specific numbers out there. For example, a college might say it would shut down if 10 percent of students contract COVID only to find that fewer students than expected enroll, giving the college extra capacity for isolation and quarantine.

"The charitable reason for why institutions are not publishing this information is things change and change rapidly and so you need to have flexibility," Marsicano says. "But it can be unnerving for students and faculty and staff and families to hear, 'Hey, guys, just trust us, we’ve got this,' without seeing the written plan."

Michael A. Olivas, an emeritus professor of law at the University of Houston and former interim president at Houston's Downtown campus, and an expert on higher education law, doesn't believe publishing criteria for closure affects a college's liability significantly one way or another. He also says using such benchmarks may not give a university any particular protection from liability.

Most colleges that have published such criteria, he points out, have included vague or hedging language that leaves room for discretion. As for those colleges that are publishing specific numerical benchmarks, "Any school that’s saying we’re going to close down at 10 percent is starting to make plans at eight," he says.

Berea's president agrees that publishing specific numerical thresholds gives college administrators less flexibility, but he suggests that might be a good thing.

"We will definitely owe an explanation to our community if we reach one of those metrics and don't close," Roelofs says. "Then the burden goes on us to explain ourselves, which is fair. If we’re not able to do that, then we're trying to create more flexibility than we should have in my opinion anyway."

Trinity University, in Texas, has also published some specific trigger numbers that will lead it to consider closing the campus. The university will consider closing, for example, if it has 50 concurrent positive cases among students or 20 concurrent positives among employees. Tess Coody-Anders, Trinity's vice president for strategic communications and marketing, says the university is in the process of revising its published criteria and potentially adding new indicators now that students are on campus and administrators have learned more about the university's testing and contact tracing capacities.

Coody-Anders says the university's approach has "been to be as fully transparent as we could be so no one is surprised if we have to make adjustments."

"We believe we have developed strong capabilities to test, trace and treat," she says. "But this virus is relentless and highly contagious, and we can’t guarantee health and safety. All we can do is do our best to mitigate and blunt its impact."