You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Pexels.com

Colleges and universities pour resources into student retention efforts, sometimes without much gain. These efforts will be further challenged by the social, educational and economic effects of COVID-19.

A new paper in Science Advances doesn’t pretend to solve the student retention puzzle. But it offers a relatively simple, proven suggestion: get students to read and write about belonging in college in their first-year writing courses.

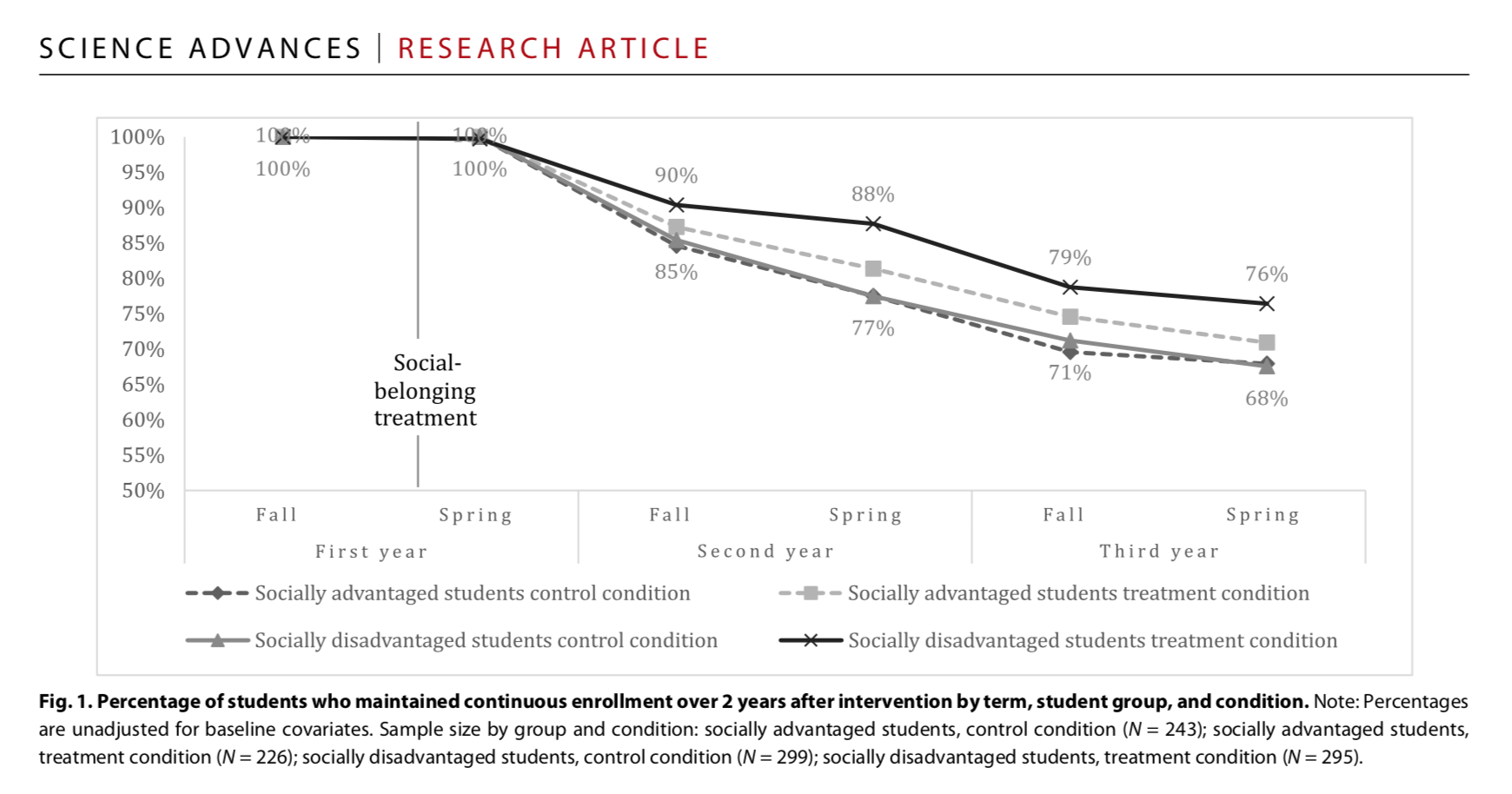

The intervention, which is much more about belonging than writing skills, made for clear results at one broad-access, Hispanic-serving institution in the Midwest. Over all, both socially advantaged and disadvantaged students benefited from the exercise, relative to control groups. Among minority and first-generation students, in particular, though, participation in the exercise correlated with significantly increased continuous enrollment over the next two academic years. Participants also reported greater feelings of academic and social fit.

Resonant Message

“Results suggest that the intervention’s belonging message resonated with students’ experiences,” even at a majority-minority institution, the study says.

Lead author Mary C. Murphy, Herman B. Wells Endowed Professor in Indiana University’s department of psychological and brain sciences, said recently that because the writing exercises studied are "inherently social -- telling the belonging stories of upper-year students and the academic and social strategies that students used to develop a sense of belonging in college -- they serve in some ways as role models for the first-year student participants.”

More specifically, she said, longitudinal analyses suggest that the exercises worked because students took on the strategies described by their upper classmates: they “made friends, joined clubs, attended faculty office hours, got involved in research, and overall formed social and academic connections.”

Such “feelings of academic and social fit in college contributed to students’ college persistence over the three years that we were able to measure,” Murphy said.

Due to COVID-19, Murphy and her co-authors have made available an online version of the intervention, in partnership with the College Transition Collaborative and Project for Education Research that Scales (PERTs).

![Source: PERTS.net I don't tell my friends, but I’m nervous for college. I’m nervous I’ll feel out of place with kids who go out to eat…or that I’ll be in for a big shock when I get what would have been a great assignment at home back with a poor grade. But college is essentially a lot of people, and all of them are different…professors are people, people who care about students and learning. I will feel a little out of my depth at first, but so does every other person there. That’s why [my college] has resources to help ease the transition, like advisers…So I’m nervous about the first part, getting through to the security, but I know that’s coming, so everything WILL be okay! Student essay from past implementation of Social-Belonging for](/sites/default/server_files/media/Screen%20Shot%202020-07-19%20at%209.18.58%20AM.png)

The paper cautions that it was highly customized to the unnamed institution studied, however. The research team worked with upper-year students and administrators to redesign first-year writing materials that would address the specific barriers and obstacles to belonging that students face in that broad-access context, and would model coping strategies that were available and effective there.

A Simple Intervention

The exercise took place in the spring term of students’ first year, during an hourlong class meeting of all required first-year writing courses. Some 1,063 students were randomly assigned either the belonging intervention or a control exercise focusing on study skills instead of belonging.

The intervention was described as a universitywide effort to learn about students’ transition to college to better serve future students. Participating students read nine stories from a diverse group of upper-year students that highlighted common academic and social challenges to belonging. The stories represented the challenges as “normal and temporary,” according to the study. Students then wrote about their own experiences with similar issues and themes. Finally, participating students wrote a letter to a future student at the university who doubted belonging there during the transition to college.

“These ‘saying-is-believing’ exercises place students in the role of benefactors not beneficiaries and encourage them to connect the core message to their lives and to internalize it, amplifying its impact,” the study says.

Within the next nine days, a randomly selected subsample of students was invited to complete an online survey about their daily experiences of social and academic adversity on campus and their daily sense of social and academic fit. They were asked questions about whether they felt like they belong on campus and whether other students accepted them, for example.

A year later, researchers invited all students in the original experiment to complete a follow-up survey about their sense of social and academic fit in college. About 300 students responded.

Researchers then retrieved academic records for all students for the two years following the intervention, through the end of the students’ third year in college.

The authors’ primary interest was in results for underrepresented minority groups -- Black, Latinx and Native American students -- and for first-generation college students of any background, or about 600 students out of the sample. The other approximately 460 students were defined as socially advantaged.

Results

College persistence was the primary outcome. Researchers found that 76 percent of socially disadvantaged students in the control group maintained continuous enrollment one year after the intervention, through their second year. Among the treatment or intervention group, that rate was 86 percent -- a significant increase. Socially advantaged students also benefited from the exercise, but not to the same degree of significance (77 percent compared to 81 percent, respectively).

Two years on, 64 percent of disengaged students in the control group had maintained continuous enrollment. In the intervention group, 73 percent of students were continuously enrolled. Again, socially advantaged students benefited, too, but not to the same degree (64 percent versus 69 percent, respectively).

Compared with campuswide figures, disadvantaged students who received the treatment were more likely to maintain continuous enrollment over the next year (86 percent versus 78 percent). The paper counts this as an “institutional” benefit.

Grade point average was the secondary outcome. The intervention boosted disadvantaged students’ GPA in the semester following by 0.19 points, on average. Two years on, the GPA gain was a “marginal” 0.11 points, according to the study. Students who struggled the most academically in their first semester of college benefited the most from the intervention on this metric.

Psychologically, based on the immediate follow-up survey about belonging, disadvantaged students in the control group displayed a significant, negative relationship between daily adversity and daily feelings of social and academic fit in college. The treatment appeared to eliminate that association, however, “as if daily adversities no longer implied to disadvantaged students a lack of social and academic fit each day on campus.”

One year after intervention, socially disadvantaged students also reported greater feelings of social and academic fit on campus in the treatment as compared with the control condition.

Now More Than Ever

Murphy and her co-authors wrote that belonging intervention materials should be context-specific, and use a design thinking and a problem-centered approach. Murphy and her group conducted extensive qualitative research in the form of student surveys, focus groups, conversations with university administrators and a review of university reports to “surface barriers to belonging experienced by students at this broad-access institution and the supports available to them.”

Several themes emerged, including that students valued the campus community and wanted to belong, but that commuting and little free time limited their ability to commit to campus activities, thus undermining their sense of belonging.

“We therefore adapted materials to acknowledge these barriers to belonging, to represent them as normal challenges, and to model ways students could overcome them to develop a sense of belonging in college,” the paper says.

Murphy said that she and her colleagues hope that colleges and universities will use their free resources “so that the exercise can benefit more students, especially racial-ethnic minority and first-generation college students who benefit most from the exercises and whose communities have been most impacted by COVID-19.”

In this moment of “widening inequalities,” she said, “exercises that help students develop a sense of belonging and fit in college -- especially if their first semester or year will be conducted online -- could be particularly important for students’ persistence and institutions’ abilities to retain students over time.”

Now more than ever, “institutions of higher education should be thinking about how to cultivate and support students’ sense of belonging in college,” Murphy said.