You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Pexels.com

There is now a body of literature questioning the link between small class size and student success. A new study of interactions between different class sizes and more than a dozen other variables within Temple University's general education program further supports the “small ain’t all” argument. It encourages educational researchers to look deeper at the effect of class size on student success, and to the effect of peers as well as teaching methods, especially in an era of constrained resources.

The study also has some hidden implications for COVID-19-era instruction, since professors teaching remotely or in hybrid models arguably have more flexibility with respect to class size.

“In terms of student race and gender, the findings for underrepresented groups contrast with previous research, which has found that smaller class sizes correlate with improved academic outcomes,” states the new study, published in Educational Researcher. That's probably because “the effect of class size is far more nuanced than historically discussed.”

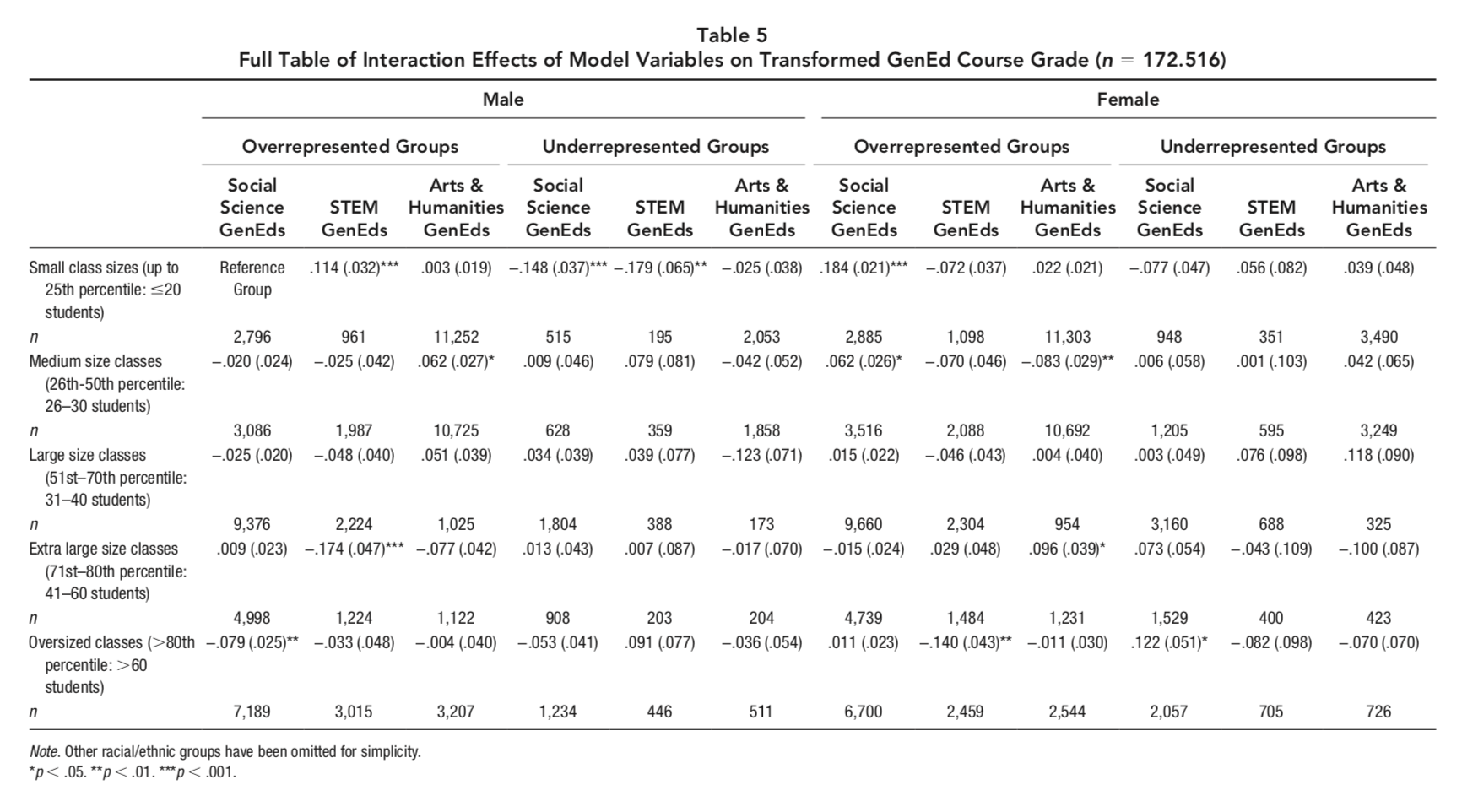

When considering small class size outcomes, compared to other class sizes, African American, Hispanic and American Indian men actually performed worse in social science courses relative to their peers, whereas white and Asian and Pacific Islander women performed best.

Medium-size classes had a more varied pattern, according to the study, yet underrepresented men and women experienced no change in outcome across disciplines.

One possible explanation? Social group theory. The influence of peers, not just professors, is a factor, according to the paper.

“Instructors generally favor smaller class sizes because it allows them to work closely and develop a relationship with their students,” the study says. “However, this reasoning does not consider learning that may happen either between students or even outside of the classroom.”

As for science, technology, engineering and math general education courses, underrepresented minorities and women of all backgrounds appear to be unfazed “by increased class sizes,” except for white and Asian and Pacific Islander women in especially large, "oversize" classes, the study says.

Only white and Asian and Pacific Islander men in small STEM classes appear to experience a potential increase in student achievement.

While STEM professors have historically attributed white and Asian male “dominance in these fields to better academic preparation compared to their underrepresented counterparts,” the paper says, the lack of a support system for other groups may help explain why student achievement for African American, Hispanic and American Indian students is “mostly static, regardless of class size.”

Perhaps most importantly, no student group in any of the fields studied appeared to be affected, good or bad, by large class sizes.

“One possible reason for this is course curricular design and instructional delivery,” the authors suggest. That is, as class size increases, instructors tend to “modify the breadth and depth of course objectives, course assignments, and course-related learning outside the classroom.”

A class size between 31 and 40 may well be the “maximum limit before an instructor is forced to incorporate more time-saving, but less academically meaningful assignments to the detriment of student learning and, ultimately, student achievement,” the authors wrote, noting this “tipping point” premise is supported by research on K-12 instruction.

The tipping point theory may also explain why most students in extra large and oversize classes “appear to experience either no increase in student achievement or an outright decline.”

Study Design

The study involved a whopping 8,000 courses within Temple core undergraduate program, across 14 academic terms. The sample included 172,516 grades from 32,766 students. Researchers used what they call a cross-classified multilevel model and loaded it with 14 variables -- six regarding students and eight for instructors and courses.

Student success is defined by course grades, and there is standing disagreement among teaching and learning scholars as to how much grades mean, if anything. The study doesn't take on that issue but rather seeks to measure how students fare by that measure, as compared to their peers, controlling for many other variables.

Lead author Ethan Ake-Little, now executive director of the American Federation of Teachers for Pennsylvania, ran the study when he was a graduate student working as a researcher in the provost’s office at Temple and dealing with real, policy-oriented questions about class size and student success.

At a big public institution such as Temple, it’s not possible to offer all students intimate class settings across disciplines. So Ake-Little and his co-authors wanted to better understand the effects of different class sizes on different demographics in different disciplines, to potentially maximize those effects where possible.

Essentially, they wanted to know how student race, gender and class size affect student performance in the social sciences, natural sciences and arts and humanities general education courses.

And to the ongoing discussions about class size, they wanted to add a more “robust quantitative analysis that incorporates a broader range of student and class-level variables,” including those that control for instruction and student experience.

Ake-Little and his colleagues converted letter grades to their 4.0 equivalents, and demographic data about students were merged with their admissions information on high school grade point average and SAT math and verbal scores.

The data set was then combined with information on instructor rank, years of teaching experience and number of times the instructor had taught the course in question -- along with course-level aggregated data gleaned from student evaluations of teaching on students’ level of interest, expected grade in the course, hours per week spent working on the course and overall student perception of their own preparation.

The 10 general education areas studied also were categorized into three domains, to fit the premise of the study: social sciences, STEM and arts and humanities.

Course size was also adjusted for purposes of analysis. Small class sizes were fewer than 25 students, medium class sizes were 26 to 30 students and large classes were 31 to 40 students. Extralarge classes were 41 to 60 students, and oversize classes had more than 61 students.

Generalizability and Implications for Faculty Development

How applicable are these findings? The authors are confident that Temple, a research institution with high enrollment and combined math and verbal SATs scores at the 55th percentile, "makes it possible to apply our findings and recommendations to a myriad of public institutions." The large sample size and variety of variables and interactions studied makes the results similarly generalizable, the authors say.

Ake-Little and his colleagues say their findings have implications for program evaluation and faculty development.

“Given the highly variable effects of class size by student race, gender, and academic discipline, it would be challenging to employ a ‘one-size-fits-all’ policy throughout the entire program,” they said. “Although we can argue that smaller class sizes improve pedagogical and curricular quality, research has shown a more valuable (and perhaps realistic) policy intervention might be to provide instructors with the professional development needed to meet individualized student need.”

For instance, they said, “because many first-generation minority students often have [trouble] developing study and time management skills and experience more difficulty navigating institutional bureaucracy, encouraging support groups and expanding access to critical academic resources may help bolster academic performance and retention for these students.”

It is possible, then, they continue, “that underrepresented students may need more significant individualized support and attention from their instructors akin to what their overrepresented peers have experienced to date.”

Ake-Little said that his next project will involve pairing these data with corresponding instructor feedback forms, to study the effects of teaching style on student success, with an eye toward class size.

On Remote Instruction and Future Research

The study considered only nonhonors, nononline, single-instructor courses, so it is very much a reflection of pre-COVID-19-era teaching. Even so, Ake-Little said the findings are relevant to remote and mixed-methods teaching in that they offer more flexibility with regard to class size than traditional face-to-face classes.

“In theory, you can take 100 students in an online class and essentially make it into smaller classes,” Ake-Little said. “This is especially true as the idea of asynchronous learning takes off.”

There’s more flexibility with class scheduling now, too, he said, in that professors can break down class blocks into “segments” that meet more regularly for shorter periods of time.

“Dealing with what’s physically in front of you is not a requirement anymore,” excluding more process-oriented courses, such as music, he said. “The question is, how do I schedule the content delivery?”

Christopher Doss, a researcher at the RAND Corporation, co-wrote a 2017 study, previewed in 2015, that found small class size changes have little impact in an asynchronous, online class setting -- something that may be especially relevant now.

Doss said the big takeaway from Ake-Little’s study is that “class size is not a monolithic construct that has just one effect.” Many factors can cause the effect of class size to vary, he said, including how instructors react to larger classes, how students react to larger classes, the subject area and exactly how big those classes are -- not just “big” or “small.”

Past studies, including Doss’s own, have tried to understand that, he said, but the new research is “explicitly trying to model how those differences might occur, which is helpful.”

Echoing a point the paper makes, Doss said the models are correlational, not causal, “so we can’t make any strong claims that these factors actually changed the effect of the class size.” But it “does represent a good starting point to think about these things more deeply.”

Taken together, Doss said his and Ake-Little’s studies “suggest that the effect of larger class sizes in online classrooms may be different than in-person because the underlying mechanisms of how class size affects students are important considerations and, by necessity, classes online have to look and function differently.”

Doss’s study suggests that class size effect is smaller in online classes, "but that is just one study looking at one flavor of online classes in one context. More research is obviously needed," he said.

Cissy Ballen, now an assistant professor of biology at Auburn University, led a 2018 study that found smaller classes help reduce performance gaps in science fields -- to a degree. While women underperformed on high-stakes exams compared with their male counterparts as class size increased, women received higher scores than men on other kinds of assessments.

Underrepresented minority students, meanwhile, underperformed compared with other students regardless of class size, suggesting that other factors in the educational environment are at play.

Ballen said the new paper matters because so many institutions are “grappling with the question of class size to accommodate more students, and there are not many studies rigorously addressing this issue,” at least in higher education, where class size is not regulated.

Noting that Ake-Little and his colleagues were careful not to endorse large classes, Ballen said the message was rather to “encourage instructors teaching large classes to seek professional development in order to meet students' needs.”

The results point to the need for similar analyses of even bigger courses, such as 700-student lectures, Ballen also said.

“As these arena-style classrooms become the norm at public colleges and universities, I think these sorts of studies will be critical to inform policy discussions.”

As for COVID-19-era teaching, in which arena-style classes are on pause, Ballen said, "Large classes, like online teaching, relate to making education more accessible to a larger number of students." Future work can apply these methods to student performance in virtual classrooms of variable sizes, she added.

Ake-Little said that focus groups with students preceded his work on class size. And some of the comments by the group members support these quantitative findings, he said, in that students have a variety of reasons for choosing larger class sizes -- including the presence of friends who may serve as a support or study group.

Sometimes students choose bigger classes because they’re more likely to have a bigger online presence, meaning that missing some class sessions for a job or other personal obligation won’t be catastrophic to one’s grade. These kinds of student needs have always existed, particularly among underrepresented minorities, he said, but have really come to the fore during COVID-19.

In any case, Ake-Little said his approach was not to make any sweeping recommendations based on his study.

“This is about who’s getting a boost and who’s not,” all things being equal, he said.