You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

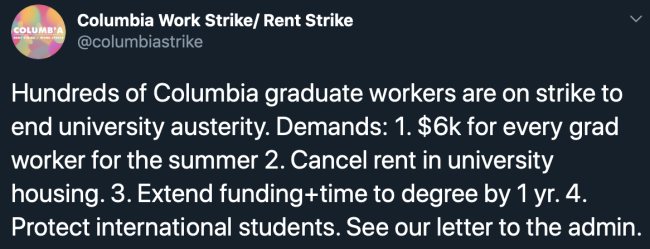

Teaching assistants at Columbia University say they won’t teach, grade or, in some cases, pay rent until the institution offers them more financial relief in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

“We take this action as a last resort,” reads a letter to the university from a group called Columbia Graduate Workers on Strike. “We wish that the Columbia University administration had adequately responded to the many petitions circulating over the last few weeks that asked for commonsense measures to protect graduate workers and tenants facing extreme financial and housing precarity in a pandemic.”

The graduate students are demanding a minimum of $6,000 each in summer funding and rent cancellations in university apartment housing. Similar to graduate students on other campuses, the group also wants extensions in overall funding and graduation or time-to-degree policies: one year for Ph.D. students and one semester for master’s students. They're seeking additional protections, such as guaranteed student status and deferred enrollment, for international graduate assistants negatively impacted by new U.S. immigration policies or travel restrictions.

“Our overarching demand is that the university end its policy of austerity towards its constituent schools,” reads the letter. Columbia is a “wealthy institution that has wrongly partitioned its budget. Even by the logic that the university simply cannot use its endowment directly to these ends, Columbia should take advantage of its endowment to use as collateral to borrow at nearly 0 percent interest rates in order to address the needs of its workers in this crisis.”

Columbia has a graduate workers’ union, which is affiliated with the United Auto Workers. The union called a strike in 2018 after Columbia refused to negotiate a first contract, arguing that graduate students are not laborers entitled to collective bargaining, as part of an ongoing national debate over the rights of student workers on private campuses. Later that year, Columbia said it was open to collective bargaining, and the groups developed a framework for negotiations.

Those talks stalled enough for the union to hold another strike authorization vote last month. An overwhelming majority of members voted yes, but no strike was called. A majority of the bargaining committee voted 5 to 3 against striking under current conditions, meaning that this work stoppage is not an official union action.

"We will continue to fight for a strong contract and fair solutions to problems rising from the COVID-19 crisis," the union said in a statement. "We expect Columbia to respect the student workers’ rights to engage in collective action."

A university spokesperson said via email that Columbia "has been actively negotiating with the union for over a year," reached tentative agreements "on a number of subjects" and made "meaningful concessions and offers on a wide variety of others, including a proposed structure for regular pay increases. Now, although the union has refrained from striking, some graduate students are refusing to teach and perform other work duties."

The strikers' demands "concern hardships related to the pandemic and are outside the scope of official bargaining discussions," the spokesperson added. "Columbia is supporting its graduate students in a variety of ways during this crisis, including a $3,000 enhanced stipend for qualifying Ph.D. candidates."

Columbia recently said that it would provide summer relief of up to $3,000 per student for graduate students on nine-month contracts. The union took some of the credit for that commitment. But it still has a series of demands, some of which overlap with the strikers’. Union goals include guaranteed summer and fall appointments, one-year funding package extensions, additional funding due to newly limited opportunities for outside work, and reimbursement for costs related to working at home.

Columbia Graduate Workers on Strike says that hundreds of graduate students are participating in the work stoppage, even if it’s not union-sanctioned. As of Monday afternoon, strikers were in 17 departments and two overlapping programs, the group said, with majority strikers in nine departments -- five unanimous. Of course, there is no picket line for this strike, which is happening online or, perhaps more appropriately, offline.

Some 150 students will be on a rent strike as of May 1, the group also said, pointing out that Columbia has offered rent relief to tenants in its commercial properties, but not to students in university housing.

Columbia says it tried to accommodate students’ housing concerns related to the public health crisis by offering them early outs from their leases and giving them $500 to move out.

Sam Stella, a second-year Ph.D. candidate in religion, said that solution presumes that all graduate students are single and otherwise unattached with family homes awaiting them. Many graduate students’ realities are far different, however. Stella’s own university-owned apartment is home to him, his wife, May Ling, and their 2-year-old son, Louie.

Stella and Ling are currently staying in his parents’ house in Michigan, partly because their spring break coincided with the COVID-19 surge in cases and they haven’t been able to safely return to New York. Doing a quick move out of New York didn’t align with their needs either: they didn’t think it was safe and they don’t really have anywhere else to go long-term. They also like where they live.

Prior to COVID-19, their apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan was financially feasible due to Ling’s full-time job. She works for a nonprofit company on issues related to tourism and has been furloughed. No word on when, or if, she’ll be hired back.

The couple pays $9,000 in the fall and again in the spring, and about $5,000 over the summer, for their one-bedroom. Stella makes about $10,000 each semester and $3,000 in the summer, plus about $500 every two weeks for living expenses. His more regular paychecks are always eaten up by day-to-day living expenses.

Stella says he won't pay rent for the summer. As of right now, he thinks he’s secured a research assistantship for that period, but he’s not sure how much it will pay. In any case, having additional summer income makes him ineligible for the full $3,000 relief that Columbia has promised.

Meanwhile, the consequences of being involved in the strike are grave. He may not be able to register for classes in the fall, and he and his family could be evicted.

“This strike is all about the immediate, emergency kind of situation people are in because of the pandemic,” he said. “I’m most concerned about rent cancellation in university apartment housing -- that’s one of demands. I’ll also note that when I learned Columbia was canceling rent for some of its commercial properties, I couldn’t believe that it wouldn’t do that for us.”

Columbia has a $10 billion endowment -- paltry among its immediate peers but still enviable among most institutions. The university could borrow against the money, as the strikers suggest, but that’s a risky proposition when economic uncertainly reigns supreme. Columbia also is facing many pressures related to the pandemic, including being one of the city’s biggest land owners at a time when many tenants can’t make rent, while also being involved in relief efforts, such as converting sports facilities into a field hospital.

The university also faces a class action lawsuit filed by a student seeking a tuition and fee refund. Strikers say that removing TAs from the equation won’t help the university prove it’s delivering on its educational promise.

Graduate assistants on a number of campuses, including the University of California, Santa Cruz, site of an ongoing wildcat strike over a requested cost-of-living adjustment, have publicly expressed solidarity with the Columbia TAs. And even some Columbia TAs who say they haven't been financially impacted by the pandemic thus far say they're joining the strike to support their colleagues.

Musa Al-Gharbi, a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at Columbia, said he's not personally affected by many of the most immediate strike concerns, but he is supporting the strike anyway, in "solidarity with others who are not as well positioned, and who are being harmed."