You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Congress included $14 billion for higher education in its last stimulus bill.

Istockphoto.com/uschools

When Congress set aside about $14 billion specifically for higher education in the stimulus bill it passed two weeks ago, lawmakers had the well-intentioned goal of most of the money going to colleges and universities that serve larger shares of lower-income students.

But lawmakers also didn’t want to penalize large institutions that don't enroll as many lower-income students.

The way Congress decided to deal with the issue, however, has complicated how billions of dollars of aid will get to colleges, lobbyists representing colleges and universities worry, and it could delay the money as campus leaders are anxiously dealing with a financial hit from the coronavirus epidemic.

“We are deeply worried the institutions' money won't go out, in the best-case scenario, for a month, and in the worst-case scenario for several months,” Terry Hartle, the American Council on Education’s senior vice president for government and public affairs, said during a webinar last week for members of the Education Writers Association.

A Republican Senate committee aide, however, said colleges should stop "whining."

In an interview on Monday, the aide said, “If they were to call me two months from now, that’s one thing. But it’s 10 days [since the measure passed]. It’s whining. For God’s sake, it's 10 days old. Let’s cool it a little.”

Trying to strike a balance between different types of institutions, the stimulus bill set aside 75 percent of the money to be distributed to institutions based on the number of enrolled students who are eligible to receive Pell Grants, the federal student aid program aimed toward those with financial need.

But to help large colleges, Congress allocated the other 25 percent of the money based on enrollment numbers of full-time-equivalent students, Pell recipients or not.

The bill is heavily weighted toward institutions with large numbers of lower-income students, the aide said. "But coronavirus isn’t solely a poverty thing. It has disrupted rich and poor, the low income and the wealthy," the aide said.

The approach, however, has led to some technical questions about how the Education Department will figure out when and how much stimulus funding institutions will get, at a time when many are in urgent need of the money.

Hartle said creating a funding formula that factors in Pell and non-Pell students could delay the distribution of stimulus dollars by months.

The uncertainty arrives as the coronavirus epidemic has forced the closure of campuses, with fears of more to come, as virtually all colleges face steep revenue declines through the summer and possibly in the fall if enrollment drops. College leaders are looking for certainty on how much help is coming from the stimulus bill.

Instead of giving out the money only based on one factor, like enrollments of Pell Grant recipients, the inclusion of full-time-equivalent enrollments in the formula means the Education Department has to combine different databases. And higher education lobbyists said it's unclear if some of the needed information even exists.

And the department isn’t able to say how long the process will take.

“Most of the money will go out through a formula that doesn’t exist. The Department of Education will have to create it, and that will slow them down,” Hartle said during the webinar.

“Because of our colleges’ emphasis on serving low-income students, we initially backed the concept of distributing funds simply on the basis of relative Pell Grant enrollment, but Congress went in another direction,” said David Baime, the American Association of Community Colleges’ senior vice president for government relations and policy analysis. “The Education Department is working as fast as they can, but we haven’t been told” when the money will be available.

The Senate GOP aide, though, said the department hasn’t given congressional staff members any indications that merging the two databases is a problem. But slowed somewhat by working remotely, department officials will need to do round after round of tests to make sure billions of tax dollars are handed out accurately.

In addition, the department still has to issue guidance on questions like how the money -- half of which must be used for emergency grants to students -- can be used, the aide said. The money likely won’t be sent out until late this month or in May, the aide said, acknowledging that the department hasn’t been able to give a date.

Associations representing higher ed institutions wrote U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos last Thursday to ask for the money to be distributed quickly. “I fear this funding will be for naught for many institutions unless the department can act very quickly to make these funds available,” American Council on Education president Ted Mitchell wrote on behalf of the associations.

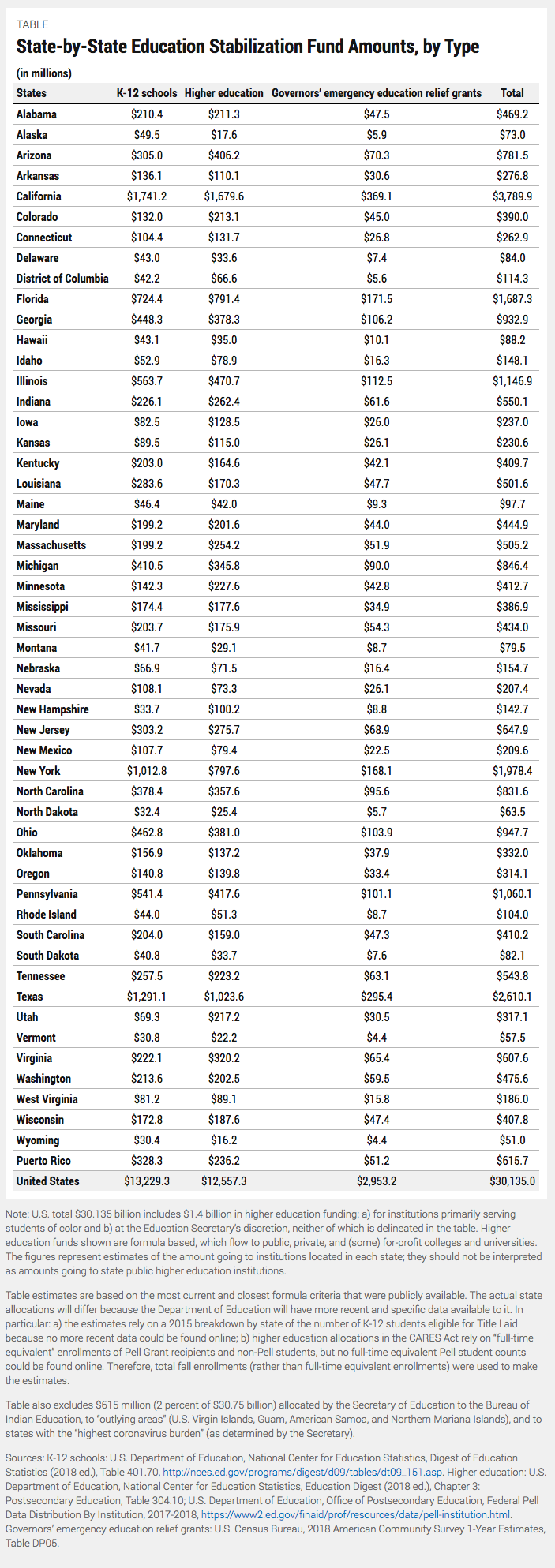

The National Governors Association also wrote DeVos on Saturday, asking the department to distribute education funds in the stimulus package within two weeks. (See below graphic from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities for estimated education stabilization funds for each state.)

A department spokeswoman said last Thursday that “we understand the necessity to move quickly to get CARES Act relief funds to students and educators. An internal group of experts is working to create the most efficient process for this, and we look forward to sharing more details with the field in the coming days.”

Filling Budget Holes

Whining or not, the uncertainty also is increasing the anxiety of institutions at a difficult time when they’re taking major financial blows.

The University of Wisconsin system, for example, plans to spend $78 million on refunds to students for room and board. And Florida State University estimates it will refund $11.5 million in room and board.

In addition, Hartle said, institutions are facing the loss of revenue from summer adult education and other programs. For example, one president of an institution in a major metropolitan area told him it is losing $4 million a month in parking revenue.

Several college presidents on Monday said they’re concerned about getting emergency grants in the stimulus to students.

Anne M. Kress, president of Northern Virginia Community College, said that even before the pandemic, half of NOVA students surveyed said they were having trouble paying for food and housing.

"Because of the economic impact of the pandemic, many of these same students who were on the financial margins before have now lost their jobs. They are struggling to learn remotely with outdated laptops or even on their phones. A large number are also student parents, working doubly hard to keep their families afloat and their own children learning. Sadly, some have the virus themselves or are caring for family members who do," she said.

“Students at Northern Virginia Community College need those funds today. They cannot wait a few months,” she said in an email.

McDaniel College, which is located in Westminster, Md., doesn’t yet have definite plans for what to do with emergency grants.

But the president of the college, Roger Casey, said in a statement that part of the money could be used to help students get technology and online access. “With our recent needed haste to move American education online quickly, the socioeconomic digital divide coupled with the country's vast urban and rural digital deserts present the greatest challenges for students to continue with their studies,” he said.

Problems are compounded for the many two-year college students facing challenges with basic needs, Joe Schaffer, president of Laramie County Community College in Cheyenne, Wyo., said in an email.

"In short, the primary reason for the urgency is to get some type of emergency financial relief in the hands of our students," he said in an email. "We are on a fast train to massive numbers of withdrawals or just disappearance of students whose lives have been impacted by the pandemic. Housing and food security are at the top of their worries and needs, primarily because so many community college students are also working (in many cases, multiple jobs and full-time)."