You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

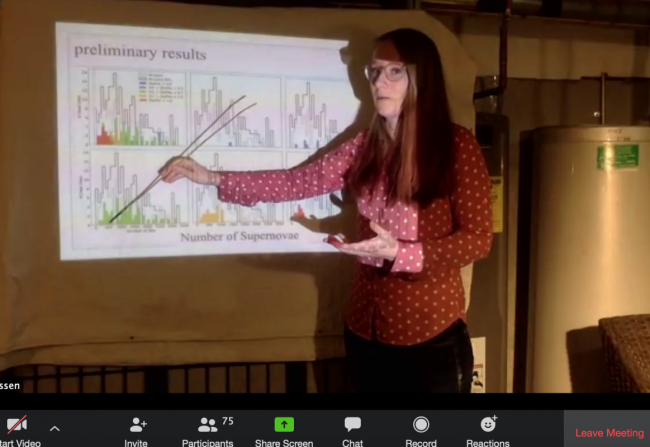

Kaitlin Rasmussen defends her thesis from a Boston basement to her University of Notre Dame-based committee.

Zoom

“Can you move the computer closer?” asks a disembodied voice. “Because we see a lot of roof.”

“Ah, I think it looks much better,” another invisible person says a few minutes later, following adjustments to the setup for Kaitlin Rasmussen’s virtual doctoral thesis defense.

Rasmussen, looking into her computer screen, half smiles and says, “I’m so excited for this to be over.” She cheers up when sees and hears that many of her friends -- including one from Australia, where it’s 1 a.m. -- are tuned in to her defense via Zoom.

Looking at the rising conference participant count on the bottom of her screen, however, Rasmussen grows nervous again. There are dozens of people here -- some 75 at one point. That’s many more than would have attended her defense in person if it were taking place as planned in her department at the University of Notre Dame.

Instead, due to the coronavirus pandemic, Rasmussen is presenting from a basement near the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she was studying temporarily -- and where she’s stuck, in her MIT supervisor’s home, for now. A white sheet is her projector screen, and a bamboo stick from the MIT supervisor’s garden is her pointer. A hot water heater frames the shot on the right.

Yet another voice booms into the Zoom call now, breaking the tension. “Are biotechnologists allowed? I promise not to ask about the p-values.”

Making the Best of It

Rasmussen is an astronomer, not a biotechnologist. But everyone is invited to her defense. She put out a call on Twitter the day prior to make the best of a disappointing situation.

“The defense is the accumulation of all of your work for the last five or six years, so it’s kind of weird,” she said. “I’ve always had plans for this. Some people have dream weddings in mind, but I’ve always had this. I imagined I’d buy some really fancy, expensive clothes and have a really good vibe, and give this awesome presentation in front of my friends and family.”

In reality, her outfit is jeans and the one dressy shirt she brought with her to Boston, way before COVID-19. And the “vibe” is muted: coronavirus casual. Still, almost everyone who matters has Zoomed in: Rasmussen’s thesis committee, minus one member, who is ill (no word on what’s wrong), family members and friends -- plus some supportive randos (this reporter included).

Initial awkwardness aside, Rasmussen’s 30-minute talk on her research on first-generation, metal-poor stars goes smoothly and quickly. There is a short question-and-answer period with all viewers before her thesis committee kicks everyone else off the call, as convention dictates.

A short while later, after answering committee members’ questions, Rasmussen emerges from the call a doctor of astrophysics. She celebrates by ordering herself a cheese pizza. Dessert is the apple crisp her MIT supervisor made for the occasion.

Ashton Merck, a historian at Duke University, also earned her doctorate this week following a Zoom defense. She celebrated with her partner in their off-campus home by finishing off the bottle of prosecco in their fridge. As soon as she’s able, she wants to invite her dissertation committee members to her home and cook everyone an air-chilled chicken dinner. But as her research was on food safety, she said she’ll be offering a vegetarian option, as well -- just in case she sent anyone down that path.

This was not the way Merck imagined her defense would go, either. But she said it would make for an interesting story eventually -- just like the new lines in her curriculum vitae that say "canceled due to COVID-19" or "delivered remotely due to COVID-19."

“It feels like that will become a marker of where people were in their career when this happened,” she said.

There were some clear disadvantages to the scenario: Merck said it was harder to gauge her committee's reaction to things, for example. And even with a Zoom "happy hour" among friends afterward, she said, “It just didn't quite feel real. Still doesn’t.”

That said, Merck, like Rasmussen, gained observers by going virtual. History defenses are typically private affairs, Merck explained, whereas 15 viewers saw her Zoom presentation. (Her committee members went into a Zoom breakout room alone to deliberate.)

Many more have since seen the informal paper Merck wrote for and on her experience. The document, which she shared with her committee members in advance, includes notes on where to position your screen, what to wear (shoes do matter, at least for the candidate!) and hints for the committee and chair (this is how you access Zoom; leave your microphone on mute).

Tri Keah Henry defended her work in criminal justice and criminology virtually this week, as well, via Zoom with colleagues at Sam Houston State University.

“My technical advice would be to become really familiar with the platform that you’re using,” she said, noting that she’d never used Zoom before practicing for the talk.

In the end, Henry said defending virtually was actually a "little less stressful than an in-person defense, simply because I had more control over the presentation." She was also less distracted by her surroundings and her audience and therefore more focused on what she was saying.

The New Normal?

Virtual defenses have quickly become the norm, thanks to the social distancing and stay-at-home orders related to the coronavirus. But they are not new. Graduate students who cannot be on campus, or whose committee members can't be there, have been Zooming and otherwise virtually defending research for years. Merck notes, for example, that her own how-to guide was inspired by thoughts from Alyssa Frederick, who conducted her Ph.D. defense remotely in November, due to a new job.

Ethan White, an associate professor of interdisciplinary ecology at the University of Florida, said his research group has had a remote component for most Ph.D. defenses for years so that family, friends and former lab mates may participate. Of entirely virtual defenses, White said he worried that a major life accomplishment could feel “anticlimactic.” Still, there are ways for committee members and other viewers to combat this, as he suggested in a recent series of tweets on the subject: leave your video feed on, consider exaggerating your engagement with thumbs-ups and nods, and make a big deal of the student passing -- even if you’re stressed about other things.

The question, White said, is, "How do we try to match the energy and feeling of accomplishment that comes from presenting to a live audience?"

He argued that there are also benefits to remote defenses, including gaining experience presenting research in this way.

"This is becoming more common," he said, "and it's definitely a skill to learn how to present effectively and enthusiastically without an audience in the room."

As for whether virtual defenses might catch on, post-pandemic, White said he hoped so -- at least as an option. Remote presentations provide more flexibility for students who are away from campus and those who have started other positions.

“The more flexibility we provide students and faculty to work and interact remotely, the better," he said. (White recently co-wrote a paper on supporting remote postdoctoral work.)

Vinicius Placco, research assistant professor of astrophysics at Notre Dame and one of Rasmussen’s supervisors there, said he thought “everything went really well with regards to technology” during her defense. But he noted helpful tweaks that could be made going forward, such as having students screen-share their slides instead of projecting them, for better clarity, or using Zoom’s webinar function to prevent viewers from accidentally interrupting a presentation.

Placco said he didn’t know if a virtual defense can ever really replace an “in-person” experience. But he called remote defenses “a very welcome option, especially in difficult times like this, but also when committee members are traveling or if you have external members from other universities.”

Placco’s own defense happened in Brazil, he said, with a U.S.-based committee member joining by Skype. He agreed that another major benefit of remote defenses is that they're inclusive.

“I could tell that Kaitlin felt really supported by family and friends, which made everything even more special and hopefully a bit less stressful to her.”

Edward Balleisen, professor of history and public policy at Duke and Merck’s adviser, said having to go with a virtual defense “was of course a disappointment. We have rituals at milestones for a reason, and they don’t conjure up the same atmosphere nor elicit the same emotional punch when mediated by cyberspace.”

Even so, the intellectual exchanges at Merck’s defense were “excellent,” he said. “I can’t say the quality of the discussion among Ashton and the five members of her committee was significantly affected.”

Could virtual defenses catch on? Balleisen said Duke, like other institutions, had a rule that only one faculty member of a dissertation committee could attend a defense remotely. Members also signed physical dissertation exam cards.

Now, he said, “I would not be surprised at all to see both of these rules fall by the wayside.”

The current crisis will likely “accelerate changes that have been in the works for some time,” Balleisen continued. As more faculty members become accustomed to digital “modes of engagement, I expect there will be fresh thinking about whether and how to deploy them,” in contexts from scholarly presentations to meetings to job searches.

Henry, the criminologist, said, “Defending in person is a very special part of the process, and if I had to choose, I would’ve defended in person. I do, however, think it’s a good option for those who can’t do a face-to-face defense for whatever reason.”