You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

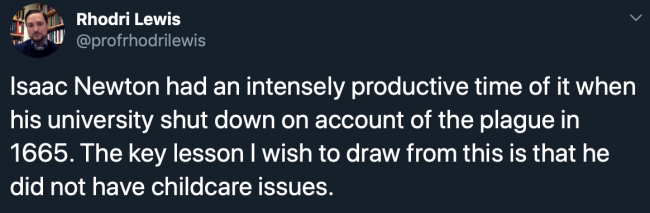

When institutions started sending students and professors home due to COVID-19, more than a few academics opined on social media that this would be a boon for research productivity: the idea, presumably, was that isolation breeds creativity. A significant share of these posts mentioned Isaac Newton, who discovered calculus while “social distancing” during the Great Plague of London, starting in 1665.

Newton -- then still a student at the University of Cambridge and not yet a sir -- also watched apples fall from “that tree” on the grounds of his family estate during the plague, as a recent Washington Post essay explains. The period has since been called Newton’s annus mirabilis, or “year of wonders,” even if nearby London itself was draped in death.

The retorts came almost as quickly as these views were voiced. No, this spring will not be a time for groundbreaking insights and increased productivity, and institutions should not expect either, academics argued. Many also pointed out that Newton was not a professor during his isolation, let alone one thrusting all his courses online for the first time. Nor was he a parent, simultaneously acting as daycare provider or teacher to children displaced by widespread pre- and K-12 school closures.

The good news for faculty members is that colleges and universities appear to be listening to these reality checks about working from home. Many institutions are offering tenure-clock stoppages, for example, to mitigate junior faculty members’ concerns about losing months of writing and research time to coronavirus-related disruptions. Others are looking at different ways of supporting professors on and off the tenure track who are struggling with the logistical and emotional tolls of COVID-19.

With Children, Alone, Whatever -- It’s Hard

“I have done exactly zero writing,” said Kim Yi Dionne, associate professor of political science at the University of California, Riverside. That doesn’t mean Dionne hasn’t been working in the last few weeks, however. She's been transitioning her courses to remote formats and helping more senior colleagues do the same. How do you lecture via Zoom, they’ve asked her. How do you schedule office hours on Google Calendar?

As a scholar of public health, Dionne had the mental jump on many of her peers: she foresaw campus shutdowns weeks ahead of time and began to prepare. She was lecturing online and telling students not to attend class in person if they felt uncomfortable doing so, or ill, before it became official policy. Dionne also gave her graduate teaching assistants clear guidance on how to adapt their winter quarter grading, for their benefit as much as undergraduates’. Don’t sweat the details, she told her TAs. Focus on whether each student demonstrated learning, tried but didn’t quite get it and so on.

Dionne is also thinking about research projects -- including those inspired by the present public health crisis.

But mostly, she said, “I've been trying to triage and think what responsibilities do I need to bow out of in order to make the next couple of months work.”

Dionne is convinced her own children, ages 7 and 12, will be out of school until the end the academic year. In the meantime, she is managing their homeschooling -- no easy feat with two children who are several grades apart.

Dionne’s partner is also working from home and contributes; he does most of the after-school stuff and cooks dinner during the week.

The pandemic also coincided with Dionne earning tenure, so there's less pressure on her to publish -- for now.

Still, Dionne and others have noted that COVID-19 disruptions will disproportionately affect the careers of female academics given that women, on average, take on more household and child-rearing duties than men. And women already face bias in personnel decisions, especially in certain fields.

Of course, it’s not 1665 anymore, and male academics also are seeing their productivity thrown off by childcare duties. Rhodri Lewis, a professor of English at Princeton University, said via email that his home has “all the materials I need and a beautifully well put-together study.” But as his children's daycare closed, “and as all the babysitting options are quite properly sitting tight in their own homes, it’s 24-7 (well, let’s say 15-7, given that they do sleep) childcare!”

John Borghi, a manager of research and instruction at Stanford University's Lane Medical Library, tweeted last week that he set up an old computer because his 3-year-old child wanted to work from home, too. Soon, the child asked, “Why don’t I just press all the buttons with my tummy?"

Children aren’t the only challenge to working from home. The coronavirus has shut down laboratories, archives, libraries and fieldwork, not to mention classroom instruction. But there’s a more personal piece to the puzzle. Support from colleagues is now harder to find, at least face-to-face. And anxieties about the public health crisis itself are high.

Letisha Engracia Cardoso Brown, an assistant professor of sociology at Virginia Tech, said she knows that as a first-year professor who doesn't have children, "people might expect my productivity to increase" at home. But right now she isn't thinking about much beyond meeting the needs of her students and her family. Brown is worried about her parents’ health and job security, and about her four younger sisters. The family has no real safety net in case someone gets sick or loses work due to stay-at-home orders and the faltering economy (her father is a chef).

Brown said she’d like to help, but she’s neck-deep in student loans -- some $200,000 worth.

“I went to school so I could have more, be more,” she said, “but I wasn't expecting a crisis year one.”

Beyond the financial questions, Brown said she doesn’t know if “I’ll suddenly inherit my younger siblings tomorrow because my dad gets sick.”

So while “I can wake up and write, trust me -- writing is not the first thing on my mind.”

Productivity Expectations

Frederick M. Lawrence, distinguished lecturer in law at Georgetown University, CEO of the Phi Beta Kappa Society and former president of Brandeis University, said institutions must weigh all of these factors as they communicate with and assess faculty members going forward.

He described the rapid and radical changes in higher education in the past few weeks as “crazy and unrecognizable beyond words.”

Lawrence said “the hallmark here is going to be flexibility. We’re all learning an awful lot about technologies and techniques that have been available but have been thus far overwhelmingly underexplored or not used broadly and widely. There are start-up costs to living in this new world.” Even faculty members who have been teaching the same classes for years “are going to have a different experience teaching it in a remote format.”

While professors theoretically save time on things such as commuting while they’re working from home, he said, “if they’re doing the teaching right, they’re going to be spending more time on teaching. We cannot expect them to be as productive as they otherwise would have been.”

Chris Poulsen, associate dean for natural sciences at the University of Michigan, said that “for most people, this will not free up a lot of time, at least initially, because they’re spending a lot of time getting their courses online.” Then “there are the disruptions in where they’re working from, which may involve caregiving and taking care of kids.”

Other considerations: “For science labs, this can be disastrous to research, because you’re essentially being shut down. And people that do fieldwork or people in the humanities and social sciences who require travel to archives, internationally or even across state boundaries, are all going to have limitations on their work.”

Poulsen said that within the College of Literature, Science and the Arts, “we’re aware of the enormous disruption that this is.”

Normal expectations, he added, “are going to be loosened, depending how long this continues, possibly by quite a lot.”

What Institutions Can Do

So far, loosening expectations at many institutions means giving assistant professors another year or, less commonly, six months, on their tenure clocks. Scores of institutions have already announced new policies to this effect, making them automatic or allowing professors to opt in or out, according to a crowdsourced list that grows daily.

Santa Clara University, for example, said in a tenure-clock announcement, “We understand that your work as a teacher-scholar may be impeded by the sudden and dramatic changes required from faculty this winter and spring to teach online, as well as disruptions in research and conference travel, additional need to care for family given school closures, and more.” Given these “extenuating circumstances,” the university said, “faculty may request a tenure clock extension from the provost, citing these disruptions as a reason.”

Christopher Long, dean of the College of Arts and Letters at Michigan State University, wrote an email to professors last week on "adjusting expectations," saying that anything beyond keeping healthy and social distancing and succeeding in remote instruction "can wait and should wait."

"This includes, but is not limited to committee meetings, events, sabbaticals, etc.," Long wrote. "I assure you that no one will be penalized for prioritizing this vital work. I promise to take the challenges of the present moment into consideration during annual staff and faculty reviews and in the tenure, reappointment, and promotion process. When evaluating your colleagues, I will ask you to do the same. We have entered uncharted territory, and it would be unjust to expect business as usual."

Santa Clara and a number of other colleges and universities are allowing faculty members to opt out of collecting students’ evaluations of their teaching for the winter and spring terms. This is in line with new COVID-19-related guidelines from the American Association of University Professors and the American Federation of Teachers, which say, in part, that teaching evaluations during the disruption should not be used to punish affected professors.

In Poulsen’s college, teaching evaluations will continue, as some professors will “teach brilliantly” online and want record of that, he said. But, consistent with AAUP guidance, these evaluations will not negatively impact any professor.

Poulsen said that institutions might also consider compensating faculty members -- where possible -- for private childcare. Some departments at Michigan have also found funding to help faculty members pay to upgrade their home internet speeds.

Dionne, at Riverside, said teaching remotely involves secretarial-type work, such as scheduling online office hours, and that institutions might assign staff members to help. She was adamant, however, that any increased administrative work related to remote instruction should not fall on graduate students' shoulders.

Lawrence warned that institutions need to think about professors’ mental health and sense of professional community during this period of remote work, as well. Speaker series may be arranged online, for example, he said, and mentorship of junior faculty members must be strengthened, not abandoned for lack of face-to-face meetings.

In some cases, academics have arranged their own virtual communities. Historians at the Movies, or #HATM, is a group of historians who watch a given movie “together” at the same time and simultaneously discuss it on Twitter. Previously, the group met once per week. Now it’s meeting three times a week.

“While we all share concern over the virus and our global community, we also understand that the best way to get through this is by doing it together,” said Jason Herbert, a Ph.D. candidate in history at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, who is now teaching at a private high school in Florida. “With no sports on TV and little opportunity to share physical company with friends and family, we are at least trying to replicate some sense of community online via a shared love of history and film.”

Herbert, creator of #HATM, said he’s received “a bunch of messages telling me how much people are enjoying the extra #HATM nights, and that means so much to me.” (Next up is Netflix’s Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C. J. Walker.)

An adjunct humanities instructor in Los Angeles who teaches six courses at three institutions said the same of the community she’s built online, tweeting as @thephdstory and under the #AcademicTwitter hashtag. It’s always been valuable, she said, but is especially so now that she’s at home 12 hours per day with her 3-year-old daughter. (Perhaps ironically, the instructor had been organizing an in-person #AcademicTwitter retreat for this summer that may be canceled due to COVID-19.)

Thinking About Adjuncts

The instructor, who did not want to be named because of the controversial topics she sometimes addresses on Twitter, said adjuncts are used to uncertainty. But there is more of that now.

“I’m always having to juggle school policies and academic calendars, but that flexibility is heightened,” she said. “It’s harder for me to keep track of deadlines and policies and ways to communicate.”

Two of the professor's courses already were online. The trickiest adjustment for the remaining four courses will be teaching one course synchronously as required by one of her three employers.

Another worry is whether she can rely on colleges offering her jobs next semester. Enrollment might fall due to COVID-19, meaning canceled course sections, she said, but it may also increase if people who have lost jobs in the interim choose to enroll.

The AAUP-AFT guidance on COVID-19 says that no instructor should lose out on promised pay due to the coronavirus. It notes that adjuncts are particularly vulnerable to the disruption, and says that all faculty members and graduate students should be compensated at a reasonable hourly rate for working to move courses online. Paula Krebs, executive director of the Modern Language Association, is advocating through her own position for programs to find ways to pay adjuncts for this kind of extra work. Funds might be available due to canceled travel plans, for example, she said.

“The least you can do for an adjunct you’ve forced to change teaching methods midsemester is 1) pay for their time making the change and 2) guarantee that they will be able to use what they just learned by teaching for you again next semester,” she said.

The American Historical Association is also pressing institutions to compensate part-time faculty members fully for already scheduled summer and fall courses. It signed on to a statement from the American Sociological Association and other groups Monday urging the same.

The sociologists' statement praises institutions for "quickly taking steps to recognize the parameters of our current context and encourages all institutions of higher education to consider appropriate temporary adjustments to their review and reappointment processes for tenure line and contingent faculty."

Whatever institutions do to support disrupted faculty members, Lawrence said they need to communicate with them about these policies early and often.

“This is disconcerting time for everybody,” he said.