You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Jeff Reinking via Getty Images

In a swift reversal of a free speech policy it staunchly defended just a week ago, the University of Louisville has ordered a student who distributed anti-gay literature at a LGBTQ Studies course to have no more contact with the professor of the course or the students enrolled.

University administrators initially responded to the incident, which left LGBTQ students and the professor feeling targeted, by citing state law and university policy that prohibits public institutions from limiting students' free speech rights. As result, university administrators said they could not prevent students from entering buildings or classrooms on campus to express themselves as long as they did not disrupt a class in session. The university was also following the guidance of its attorneys, who said the pamphlets the student distributed did not classify as hate speech, said John Karman, director of media relations.

University administrators initially responded to the incident, which left LGBTQ students and the professor feeling targeted, by citing state law and university policy that prohibits public institutions from limiting students' free speech rights. As result, university administrators said they could not prevent students from entering buildings or classrooms on campus to express themselves as long as they did not disrupt a class in session. The university was also following the guidance of its attorneys, who said the pamphlets the student distributed did not classify as hate speech, said John Karman, director of media relations.

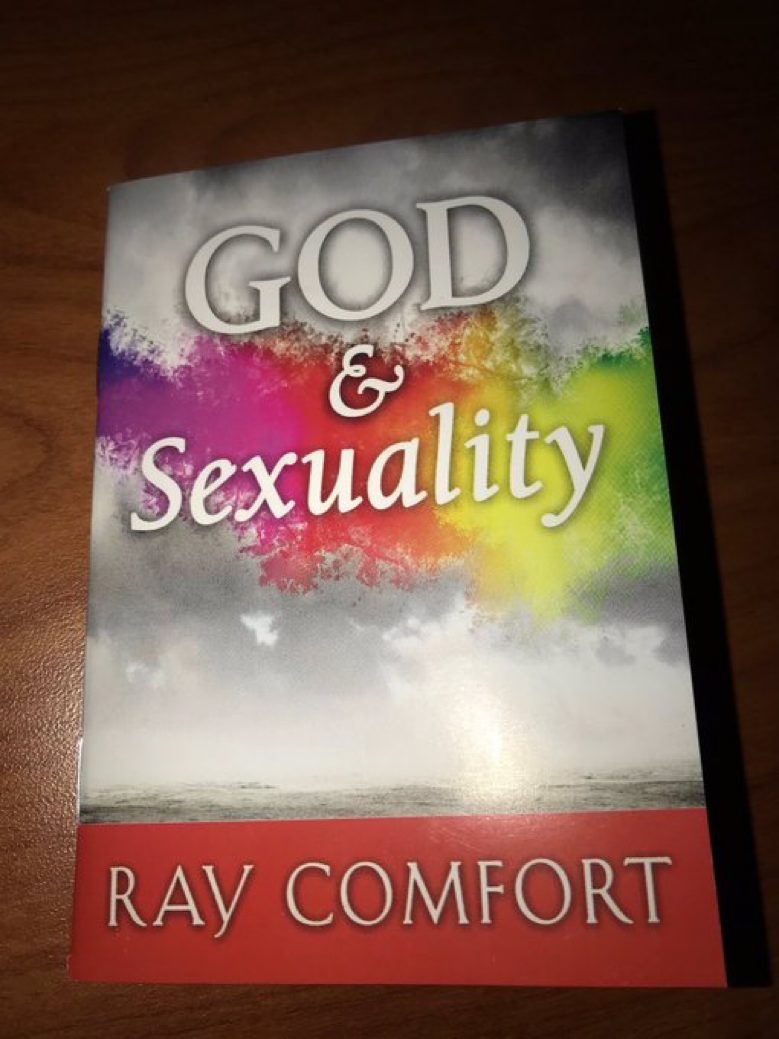

The unnamed student, who was not enrolled in the class, distributed the material on Jan. 28 before the class had begun and then waited outside the class once it was in session, according to news reports. The incident was reported to administrators, who met with the student and said he was free to return and distribute more pamphlets to the class.

It's unclear what has changed since the representatives of the office of the dean of students met with the student and made the original determination. Karman declined to provide more detail. What is clear is that its reversal has left many people on and off the campus puzzled.

While members and supporters of the LGBTQ community on campus were pleased, Martin Cothran, spokesperson for the Kentucky Family Foundation, a conservative organization that supports the student's right to distribute written material, criticized university administrators for “buckling to the pressure of a particular privileged ideological group on campus.” His organization does not support gay marriage rights.

Ricky Jones, chair of the Pan-African studies department, who wrote a searing opinion piece criticizing the university’s decision last week, said he was happy with the university's reversal.

“I can’t speak to what made them change their mind,” he said. “We argued from the beginning against the fundamental stance that this was a free speech issue … We never said that the student couldn’t pass out the materials; we made the argument that him returning to that class was unnerving and odd.”

University president Neeli Bendapudi and other administrators met with the students in the class and their professor on Feb. 6 and told them there was very little the university could do “without inciting legal pushback,” said Charlotte Haydon, a trans woman who is a student in the class. Bendapudi seemed “earnest in her feelings of regret that things weren’t handled as well as she would’ve liked,” Haydon said.

Administrators then met with Kaila Story, who teaches the LGBTQ Studies course, on Feb. 12 and offered to issue a no-contact order instructing the student pamphleteer to stay away from the class and the students, said Jones, who got involved in the incident because Story has a joint appointment in his department.

“When he targeted a class in that way and shared an intention to return, we saw that at the beginning as something different,” said Jones, referencing the “hundreds” of campus shootings that have taken place across the U.S. “We saw that as a risk.”

Jones believes the incident crossed the line of free expression and into the territory of threatening behavior, because the student had a clear intent to return to the class. The student shared this intent with student affairs officials, who, according to Jones, allegedly told the student he could return to the class and distribute more pamphlets as long as he gave the professor 48 hours' notice. Karman, the university spokesman, said he could not confirm this agreement was ever made.

Free speech on Kentucky’s college campuses is governed by a 2019 law that emphasizes the right of students and faculty members to express whatever viewpoint they choose without the restrictions of “free speech zones.” The university's Code of Student Rights and Responsibilities does say students and organizations “must not in any way interfere with the proper functioning of the university” and that the university “reserves the right to make reasonable restrictions as to time, place, and manner of the student demonstrations.”

The university will continue to keep a police officer stationed outside the class for the remainder of the semester, Karman said.

Ariana Valasquez, president of the Louisville chapter of the Young Democrats, a student organization, said in a statement that the university is responsible for upholding free speech but also for protecting students from harm.

“The protection and safety of the students, as well as the institution of a healthy learning environment, is important to a functioning university that promotes academic discourse in a safe space,” the statement said. “When the academic boundaries of trust and safety are threatened, the university can not provide a safe space for academic discourse.”

A student showing up to a class with a differing opinion does not constitute a safety risk, said Cothran, of the Kentucky Family Foundation,

“Our concern here is that the university might be considering alternative ideas as safety threats,” he said. “That itself is a threat to the free exchange of ideas.”

The no-contact order officially stands between the student who distributed pamphlets and the class itself, Karman said.

Louisville’s Code of Student Conduct lists “restriction of contact with specific students, faculty and staff” as a sanction for an array of conduct violations, such as disruption of normal university processes and harassment. The legality of the no-contact rule depends “significantly on who the student is prohibited from contacting and the basis on which the order is imposed,” said Adam Steinbaugh, director of the individual rights defense program for FIRE, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education.

“If it's to prevent disruption of a particular class, that may be enforceable,” Steinbaugh wrote in an email. “But if it’s not narrowly tailored to directly advance the university's interests in a nondisruptive learning environment, it may present First Amendment problems.”