You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Wikimedia Commons

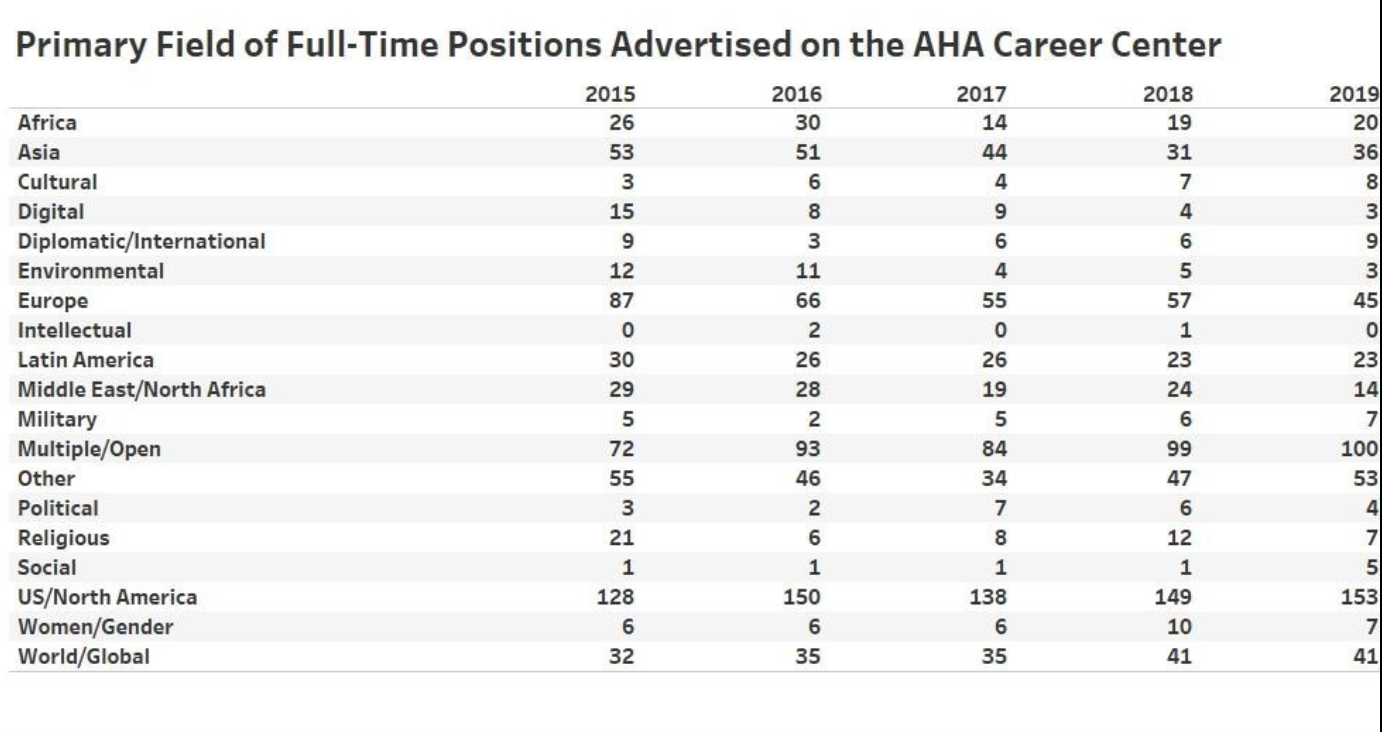

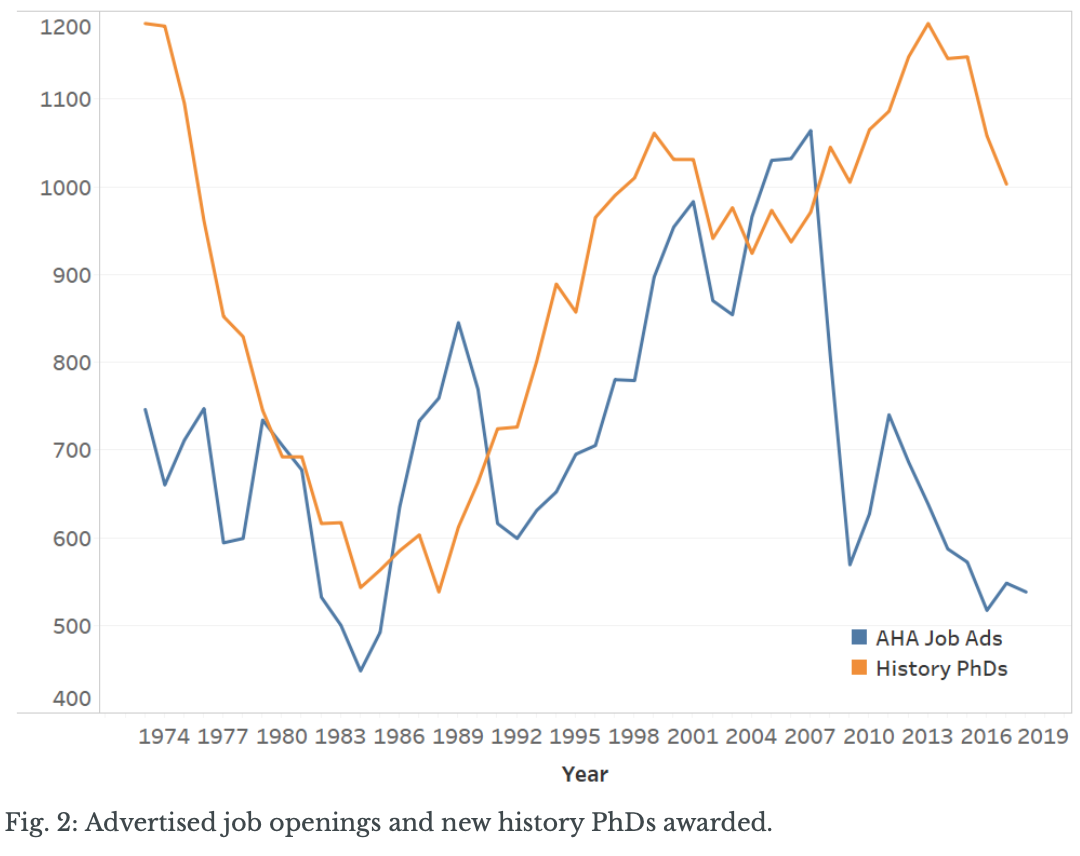

The number of advertised full-time faculty jobs in history declined slightly last year, after increasing slightly the year before. Yet the relative stability in job numbers in 2018-19 signals that the history job market is normalizing after years of steep declines prior to 2017-18.

At the same time, fewer Ph.D.s in history are being awarded.

The new data appeared in the American Historical Association’s annual jobs report, released Wednesday. The report is based on jobs posted to the AHA Career Center and the separate H-Net Job Guide. About 25 percent of historians work outside academe, so the report does not reflect the entire jobs outlook, but it is considered representative of overall disciplinary trends.

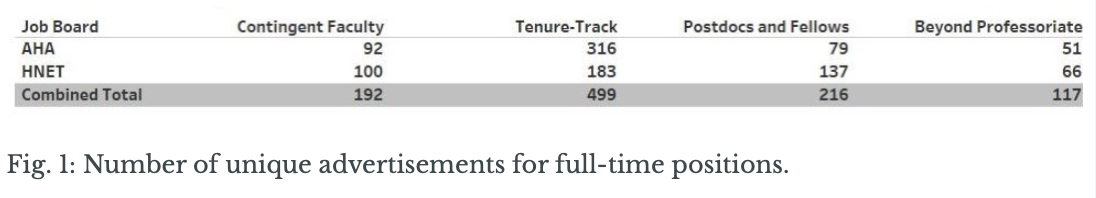

“We may have reached a point of stability in the academic job market,” reads the report, written by Dylan Ruediger, an AHA staffer. During the 2018-19 hiring cycle, the AHA Career Center hosted ads for 538 full-time positions, making for a 1.8 percent decline year over year.

Ads for jobs beyond the professoriate, in particular, dropped from 59 to 51, accounting for much of the overall decrease.

Tenure-track jobs declined from 320 to 318, as postdoctoral fellowships rose from 78 to 79, and non-tenure-track positions increased from 91 to 92.

On H-Net, the number of history job ads dropped by about 9 percent.

Together, Ruediger wrote, “the two leading job boards indicate a modest 2.9 percent decline in tenure-track positions and a 5 percent decline in contingent faculty positions compared to 2017-18.”

Together, Ruediger wrote, “the two leading job boards indicate a modest 2.9 percent decline in tenure-track positions and a 5 percent decline in contingent faculty positions compared to 2017-18.”

Like the humanities generally, “history has seen decreased enrollments and a decline in the number of majors since the recession of 2008-09,” the report also says. “This long-term trend might have finally bottomed out, thanks to the creativity and determination of faculty who are reinvigorating history courses, and departments willing to put student interests and outcomes at the center of their curricula.”

Meanwhile, “departments have responded to years of difficult academic hiring cycles by shrinking the size of their doctoral programs.”

Ruediger’s analysis says that history Ph.D.s who graduated in the past decade faced fewer opportunities and more competition “than any cohort of PhDs since the 1970s when departments significantly cut admissions to their doctoral programs.”

As some historians are calling for similar steps to be taken now, he said, some departments have “quietly been shrinking for some time, a trend that continued last year.”

In 2018, for example, 1,003 students earned history Ph.D.s, compared to 1,058 in 2017. It’s “no blip,” Ruediger explained, as the annual number of new history Ph.D.s has declined 15 percent over all since 2014, reflecting “programmatic decisions made five to seven years earlier.”

The “shrinking size of Ph.D. programs is a lagging indicator of a discipline with a diminished footprint inside American colleges and universities,” the report says. “It also reveals that departments are not complacently carrying on with business as usual but making hard decisions about how many students to admit and how best to prepare those they have.”

Ruediger notes that the “ongoing sluggishness of academic hiring exists within the context of demographic changes transforming higher education as a whole.” Overall enrollment in colleges and universities has declined for eight consecutive years, down two million students since 2011. History majors and enrollments have declined even faster than that, “as general education requirements have shifted and data showing positive career outcomes for history majors have been ignored.”

While academic hiring doesn’t directly follow these trends, Ruediger wrote, faculty members “consistently report feeling that their ability to make the case for replacing or adding tenure lines hinges on the number of students enrolling in history courses or, in some cases, the number of majors.”

The AHA’s report warns that overall college and university enrollment is projected to decline further in the years ahead.

Over all, in 2018-19, the two job boards advertised a total of 691 faculty positions open to historians, 499 of them tenure-track positions. Most of those were assistant professorships. From a survey of advertisers on the AHA’s Career Center, the association determined that each of the 53 newly hired assistant professors on which they compiled data had graduated recently, about two-thirds within two years of hire. Still, 13 percent of tenure-track openings for assistant professors went to applicants six or more years beyond their Ph.D.s.

Contingent positions -- instructors, lecturers, clinical professors and visiting appointments -- made up 28 percent of full-time faculty positions advertised last year, unchanged from 2017-18. Adjunct jobs are underrepresented in the report.

As they did last year, when the AHA began tracking jobs by institution type, research universities dominated academic hiring: 56 percent of all tenure-track positions in 2018-19 were at research universities, according to the report, as were 51 percent of full-time, non-tenure-track positions and two-thirds of all senior hires.

These numbers stand unchanged from last year and are at odds with the overall composition of history faculty, “most of whom are employed at teaching institutions,” the report says. “The concentration of tenure-track positions at research universities, should it continue, clearly pertains to Ph.D. candidates entering the academic job market.”

Over all, Ruediger wrote, “We are now entering our second decade of anemic academic hiring, during which thousands of early-career historians have experienced disappointment, anger, and despair at the limited number of entry points into stable faculty employment.” This should “prompt us to recognize the accomplishments of historians building careers and contributing to our community from outside the professoriate: we will need their help to demonstrate the value of historical thinking beyond the academy.”

Even so, he said, “majors and undergraduate enrollments remain the foundation of the discipline within higher education, and improving the faculty market means strengthening that foundation.”

In good news, there are signs that years of declines in enrollments and majors may be leveling off and even beginning to “rebound,” Ruediger said. “But challenges to the discipline remain considerable: arguing for the value of that discipline is work we must do together.”

The Modern Language Association released its annual jobs report in November. It reflected similar trends to the AHA’s. For the sixth year in a row, that MLA report says, the number of positions advertised in the MLA Job Information List (JIL) decreased. But the decline for 2017-18 was “significantly smaller than it was in 2016-17, when both editions, English and languages other than English, suffered a drop of 11.5 percent.” In 2017-18, meanwhile, “the number of English positions dropped from 837 to 828 (a 1.1 percent decline), and the number of positions in languages dropped from 808 to 770 (a 4.7 percent decline).”

Robert Townsend, director of the Washington office of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, is currently completing the 2017-18 departmental survey of faculties in the humanities fields. Details are forthcoming, but Townsend said Wednesday that data indicate there has been little change in the “number of faculty or the mix of tenure and non-tenure-track faculty in these departments” since the first such survey, in 2012.