You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

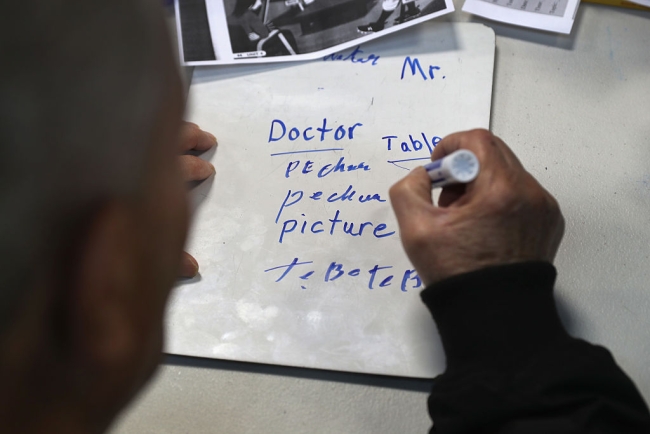

Getty Images/John Moore

When a new law in California started requiring colleges to accelerate coursework for learning English as a second language, Cuyamaca College in El Cajon was already there.

Assembly Bill 705, which took effect in 2018, requires colleges to maximize the likelihood that students will complete transfer-level English and math courses within a year of enrolling. It includes both developmental education and ESL sequences, although it identifies ESL programs as distinct from remedial courses and requires institutions to encourage ESL students to complete transfer-level English within three years instead of one.

"Most of my colleagues across the state seem to be in a panic because of AB 705," said Guillermo Colls, faculty chair for ESL at Cuyamaca. "Here at Cuyamaca, we're not scrambling because we did that before AB 705 came around."

Cuyamaca shortened its ESL sequence from seven levels to five. Students can finish in as few as three levels if they are successful in classes. The college started the work in 2016, Colls said, after faculty members attended the annual California Acceleration Project conference and realized that many of the techniques used in developmental English could be applied to ESL.

The results have been positive. Students are finishing the ESL sequences faster, according to data from the college. While no students who entered ESL at the lowest level of the sequence completed transfer-level English within three semesters in 2015, 16 percent of students did so in 2017.

"These language-learning students have been capable of a lot more than we thought for a long, long time," Colls said. "It’s not something to be afraid of or to resist."

Kathryn Wada, a professor of ESL at Cypress College in California, was a member of the statewide AB 705 implementation committee. She, with help from colleagues, pushed for an amendment to the original legislation that distinguished ESL as separate from remedial coursework.

Her college now offers certificates in ESL to encourage students to keep moving forward, as she said research shows ESL students often make it close to the transfer finish line but not quite over it.

Practical Concerns

The time is ripe for more attention to ESL, as California alone enrolls more than 50,000 new ESL students in its community college system. But while most faculty members and researchers agree that the profession needs reforms, there's a tension between the desire for acceleration and the practical amount of time it takes to learn a new language. As policy makers, advocates and institutions push to reform developmental education, ESL programs are often lumped into the conversation.

At the City University of New York, ESL faculty are "unsure of what the future holds," according to Heather Finn, associate professor and deputy chair of ESL at the Borough of Manhattan Community College in the CUNY system.

As of fall 2022, CUNY will no longer offer noncredit remedial courses. While it's clear how developmental education will move forward, Finn said questions remain for ESL.

"Up until very, very recently, no one thought about ELL with the change," said Sharon Avni, a professor of literacy and linguistics at BMCC, referring to English language learners, another name for those in ESL programs. "What’s happening now is, in a way, almost a catch-up effort."

One of the issues is a lack of research, particularly about ESL students who attend community colleges. While Avni has taught a corequisite ESL course and had a positive experience, there's still not enough research for her to say it's the right way forward.

"We're in a bit of an experimental phase with all of this," she said. "It's hard to know what's bad and what's good."

Linda Harklau, a professor of language and literacy education at the University of Georgia, also wants more information on what works.

Corequisite courses, which combine ESL teaching with a credit-bearing course, are being pushed heavily, Harklau said, and there's not a lot of attention paid to instruction reform.

"Basically, the corequisite model is attractive to administrators because it saves them money, so it makes it really hard to argue for experimentation," she said.

But instructors in this field want to look at other options, like recognizing the "complete linguistic repertoire" of students, she said. This is difficult because non-ESL faculty don't see teaching English learners as their jobs and don't have any ESL training, so it's hard for students to get support further along in college.

There's also a "stretch model," which stretches corequisite courses into two semesters so students get more consistent support. Likewise, other proposals would let ESL courses count as humanities credits and allow students to use directed self-placement to determine whether they take ESL courses at all.

"What frustrates me is the sheer lack of research or even interest in documenting programs like these," Harklau said. "We need to be able to experiment with multiple models, and I think right now there’s a tendency to just focus on corequisites."

While many questions remain, California seems to be making progress with acceleration. Research has found that colleges that integrate ESL courses -- combining writing and reading into one course, for example -- are helping students complete transfer-level courses at a higher rate, according to Olga Rodriguez, a research fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California.

Rodriguez argues that there are right ways to accelerate ESL sequences. If students are aware of supports, like writing centers, then they can continue to learn the language in other courses.

Colls at Cuyamaca said acceleration can be harmful if a college just cuts levels without actually changing the curriculum. Cuyamaca integrated reading and writing, uses "real world books" rather than textbooks and implemented an accordion system that helps students move along at the appropriate pace. Instead of going from one to two, Colls said, they take "1A" and then, if they need more practice, "1B." If not, they go straight to "2A."

"This can be a real blessing to your students," he said. "It’s working here."