You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Istockphoto.com/Martin Janecek

Two days. Two reports citing the same data. Two different conclusions.

On Wednesday, the Texas Public Policy Foundation, a conservative think tank, published a report arguing that state disinvestment in higher education is a myth. Then this morning, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a progressive think tank, published its own report saying deep cuts to state funding for higher education have shifted the burden of the cost of college onto students.

Both reports pointed to data on national averages from the State Higher Education Executive Officers association’s annual State Higher Education Finance report. But how can two different reports cite the same data to reach different conclusions?

The answer lies in large part in the time frames examined. The Texas Public Policy Foundation report looks at data dating back to 1980 when drawing its conclusions. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities only goes back a decade. Other aspects, like how authors adjust data for inflation and how they analyze and interpret them, also likely play a part.

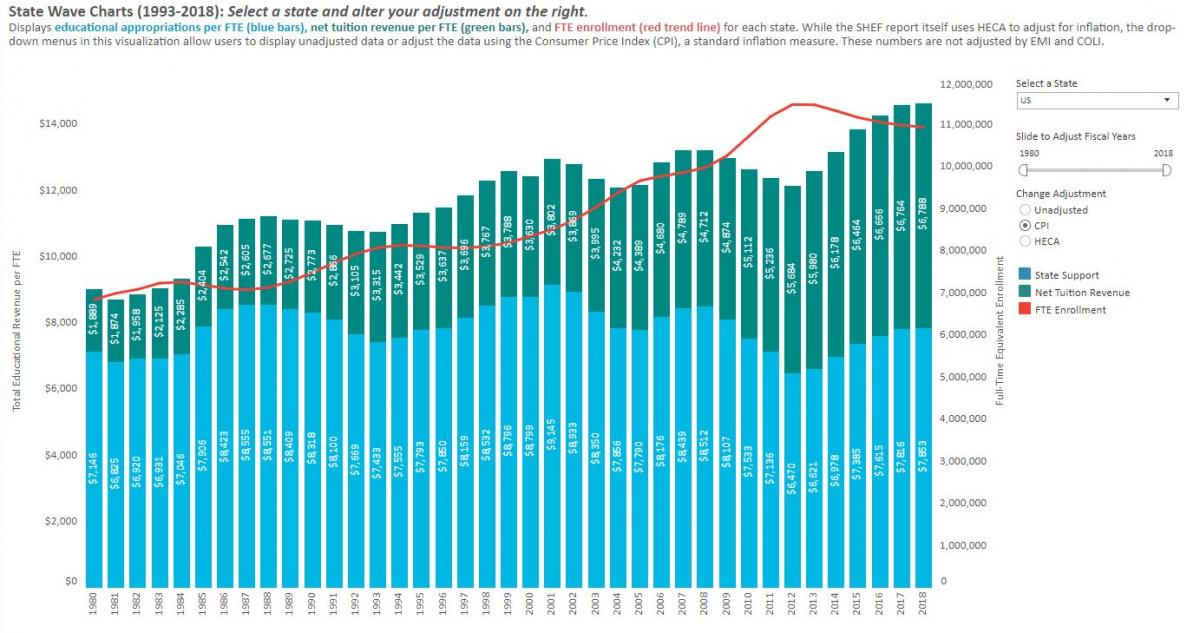

No matter how you adjust the data for inflation -- using the Consumer Price Index or the Higher Education Cost Adjustment -- the SHEEO data show a series of peaks and troughs in state support for higher education over time as recessions punctuate the economic cycle. State support per student was lower in 2018, the most recent year for which data are available, than it was in either 2001 or 2008. Depending on the inflation adjustment, it might have been higher in 2018 than it was in 1980, though.

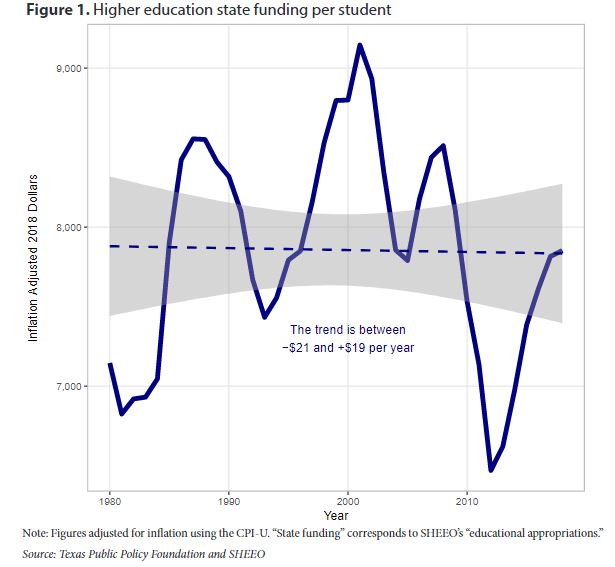

The Texas Public Policy Foundation report builds its argument on that last point. It uses the CPI-U, a consumer price index for urban consumers, and finds that state funding per student increased by $707 between 1980 and 2018. Don’t worry about year-to-year changes in state funding, argued the report's author, Andrew Gillen, a senior policy analyst at the foundation. Pay attention to trends over time. Long-term trends show state funding to be cyclical, falling during recessions and increasing during recoveries, he wrote.

Gillen performed a regression analysis on the historical data, finding that states tended to disinvest in higher education at a rate of $1.20 per student per year over the last four decades. But he found a large margin of error. Changes in state funding could actually average anywhere from decreases of $21 to increases of $19 per student per year, he wrote.

“If you are a state policy maker, then you’ve probably been hearing from higher education institutions in your state saying we’ve seen a lot of cuts in state funding over time and this is why we have to increase tuition,” said Gillen, who has argued against the idea of long-term state disinvestment in the past. “This report stands that on its head. It says, actually, there haven’t been cuts in state funding over time that are persistent.”

State funding is volatile but within a “narrow range,” Gillen’s report argues. He also struggled to find a relationship between state funding cuts and tuition increases, and concludes that colleges have more total funding today than at any time in the past.

On the last point, different sides seem to agree on SHEEO's data. No matter the time frame nor the adjustment, net tuition revenue per student was higher in 2018 than at any point since at least 1980, in large part because net tuition revenue per student has grown year after year.

But those who compile the data for SHEEO take issue with some of Gillen’s other conclusions. While Gillen might view state funding levels as changing within a narrow range, some describe it as fluctuating widely.

Short-term swings in state funding for higher education are significant, said Sophia Laderman, senior policy analyst at SHEEO. Such "crazy variation" can stress institutional budgets even if cuts are restored over time. It's hard for colleges to budget for the future when they know sudden cuts to state funding are a way politicians balance states' books in hard times.

And all of the evidence SHEEO examines suggests state funding declines are the biggest cause of tuition increases.

It is not a one-to-one relationship -- that is, tuition doesn’t increase $1 for every $1 state funding is cut. And tuition doesn't fall when state funding increases. But that doesn’t necessarily invalidate the idea that cuts in state funding contribute to tuition increases.

“I worked in Colorado during the Great Recession,” said Andy Carlson, vice president of finance policy and member services at SHEEO and former budget and financial aid director at the Colorado Department of Higher Education. “The state very intentionally allowed institutions to raise tuition significantly as an offset to state funding cuts. The relationship was laid out in policy.”

Those at SHEEO credited Gillen for transparency, however. They were able to reproduce his calculations, even if they didn’t think those calculations pointed to the conclusions the author reached.

Similar Data, Different Take

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, which cites SHEEO data as well as other data, didn’t show its work as clearly. The experts at SHEEO were unable to reproduce its calculations Wednesday.

The CBPP report, written by Michael Mitchell, Michael Leachman and Matt Saenz, argues that state funding for two- and four-year colleges in the academic year ending in 2018 was more than $6.6 billion below funding in 2008, after adjusting for inflation.

On average, states spent $1,220, or 13 percent, less per student in 2008 than they did in 2018, the CBPP report said. The think tank has produced similar reports in the past.

This year’s report acknowledges that between 2017 and 2018, per-student funding “essentially remained flat.”

That arguably glosses over the fact that SHEEO data show per-student funding rising on average across the country for the six years ending in 2018. Another increase is expected when new data come out for the next year.

“I think that piece of the story shouldn’t be ignored,” Laderman said. “States have really been making serious efforts for several years.”

The CBPP report focuses heavily on how cuts to state funding and rising tuition costs have affected today’s students, who it calls more racially and economically diverse than the students of the past. The report argues that policy makers should increase funding for public higher education, bolster need-based aid programs and create funding formulas that provide money for colleges with few resources.

“The key takeaway is that as state funding has declined and tuition has risen, students and/or their families have had to shoulder a larger share of the financial burden, and this burden is greatest for families of color and those with low incomes,” said Mitchell, senior director for equity and inclusion at CBPP, on a Wednesday conference call held in advance of the report’s official release. “This matters because the high cost of college has troubling implications for the well-being of individuals and our broader economy.”

The CBPP report also looks at how funding has changed in different states, something that could be important since national averages can obscure the way funding and tuition rise and fall in individual states and at individual colleges. Funding changes vary widely from state to state.

Gillen’s report, it should be noted, does not make an argument about whether states should provide more funding for higher ed.

“There is nothing in here that says state funding should be increased or decreased,” Gillen said. “It just says, historically, here is what happened to state funding. We can have all kinds of conversations about, ‘Do we want next year’s to be higher, lower, whatever.’”

Laderman at SHEEO stresses that the view from the state level is important. So, too, are a host of other considerations.

Public colleges and universities educate more students today than they did in 2008 or 1980, although full-time-equivalent enrollment has dropped and then flattened since peaking in 2012, according to SHEEO’s data. Today’s students are more diverse and in some cases older than students of the past. If they require different services, enroll in different programs or enroll in different types of institutions in greater numbers, the amount of money colleges and universities need could be affected.

None of that will show up in a discussion about whether state funding is up or down.

“All of these things are affecting students,” Laderman said. “We just want to reiterate that the context is really important.”