You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Women on social media face disproportionate levels of harassment compared to men. A new study says that female academics also have disproportionately fewer Twitter followers, likes and retweets than their male counterparts on the platform, regardless of their Twitter activity levels or professional rank.

Women were also more likely than men to reciprocate relationships with followers and follow back, and to follow other women.

Observers of gender dynamics, casual or expert, probably won’t be surprised by the findings. But they do have implications for scientific impact and careers and the general sharing of information. And because this study, in particular, involved health policy and health services researchers, there are implications for public health. So it’s important to understand what’s happening, and why -- as best we can, since the study was more quantitative analysis than a deep dive into the psychology of Twitter.

The short answer, said lead author Jane M. Zhu, assistant professor of medicine at Oregon Health and Sciences University and a senior adjunct fellow in health economics at the University of Pennsylvania, is that the “same power dynamics that exist in the real-world office settings seem to exist online.”

The slightly longer answer, she said, is that while women may be supporting other women and “amplifying each other’s professional voices online, men may still be considered the more authoritative voices, even within the same academic rank.”

Additionally, Zhu said, “Men may not find the content of women’s tweets as compelling as other men’s, or they may not feel obligated to reciprocate relationships and follow women who follow them.”

How many fewer followers do women get than men? Half.

For their study, the researchers identified the names and institutional affiliations of authors and speakers at the 2018 AcademyHealth annual research meeting. They excluded trainees and those without medical degrees or doctorates and then pulled Twitter data -- including the most recent 3,200 tweets -- for the remaining sample. About one-third of that group had a Twitter account, some 492 women and 427 men.

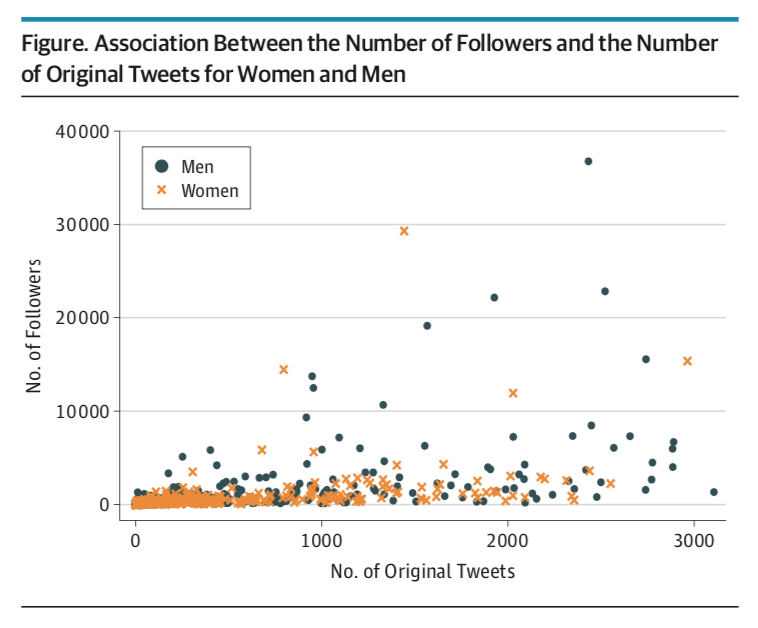

The men followed about 375 people, on average, while women followed 332. In addition to following fewer people, women had been on Twitter for less time, on average -- about 4.5 years, versus 5.1 years for men. They also had fewer original tweets, at about 71 per year, compared to 98 for men. But the study asserts that that doesn’t account for the dramatic difference in followers: 567 for women, on average, versus 1,162 for men.

Similarly, women’s tweets generated fewer average likes than men, at 316 per year versus 578, respectively. Same for retweets, at 207 per year on average for women and 400 for men. Per tweet, not just per year, the same was true. Most gender differences were between full professors.

Source: JAMA Internal Medicine

The study, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, notes that men and women are using Twitter at equal rates, and that social media offers women “opportunities for engagement, perhaps with fewer barriers than may be present in day-to-day academic interactions.” The gender disparity was also less pronounced at lower ranks, suggesting things may be changing.

Yet while some have hoped that social media would “help level the playing field in academic medicine by giving women an accessible and equitable platform on which to present themselves,” it says, the danger is that these forums “may do little to improve gender parity and may instead reinforce disparities.”

Not Just Academic Medicine

The study notes that its academic-medicine focus limits its generalizability. But academics across fields said that the findings make sense -- too much of it.

Kim Weeden, Jan Rock Zubrow Professor of the Social Sciences and director of the Center for the Study of Inequality at Cornell University, has a healthy Twitter following. But she said the study seems consistent with other, experimental research on how both men and women assess other men and women in terms of competence.

That is, “When evaluators lack background information to evaluate a person's competence or expertise, as is often the case on Twitter, they rate men as being more competent than women.”

There is a lot of research on this topic, both in and outside academic settings. Some of it pertains to student evaluations of teaching -- how students rate professors. Some it pertains to hiring practices. One study published earlier this year, for instance, found that identically qualified hypothetical candidates for a postdoctoral position with women’s names were rated as more likable than men by both physicists and biologists. Physicists rated male candidates as more competent and worth hiring than female candidates. The study also found significant racial bias: Asian and white candidates were seen as more competent and hireable than black and Latinx candidates. Black women and Latinx women and men candidates were rated significantly lower than all other candidates in physics.

Studies also have found that even when evaluators believe women are just as competent as the men they’re rating, they label women as less likeable and more hostile, Weeden said. In the context of Twitter, then, both cases would lead to fewer followers and likes for women than for men, “either because potential followers assume women are less competent or because they find competent women less likable than men,” on average. She underscored that this pattern occurs with both female and male evaluators -- or, here, potential followers.

Sarah McAnulty, assistant research professor of molecular and cell biology at the University of Connecticut, has amassed nearly 30,000 Twitter followers -- in part due to her role as executive director at Skype a Scientist. The outreach organization matches scientists with classrooms and groups of adults for video chats about various scientific topics. McAnulty is currently on a cross-country journey in her “SquidMobile” as part of that work.

Asked (via Twitter message) Monday if the study’s findings rang true with her experience, McAnulty said during a stop in the Arizona desert, “Yes, totally. People listen to men on science topics more readily, implicit bias is pervasive. There are a lot of phenomenal science communicators out there, though.” And women in biology “are certainly clawing our way toward the top.”

As for what to do about the apparent gender bias, Zhu said that it necessitates “some habit-changing strategies, not only on the part of women, but also on the part of men.” And the best place to start might be Twitter, she said, due to its accessibility -- the reason the researchers studied it in the first place. Those “with influence and power can help to advance a culture of greater gender equity, whether that be in the hospital, in research or online.”

Women Also Know Stuff is trying to change the gendered view of experience in political science by promoting female political scientists. Its history offshoot, Women Also Know History, is doing the same in that field.

Keisha N. Blain, an associate professor of history at the University of Pittsburgh and a founding member of the latter group, said that the “very decision” people make about who to follow -- or not follow -- on Twitter “tells us a lot about how patriarchy functions in academia and society at large.” And so being “intentional about following women on Twitter is certainly one important step” users can take to “address the imbalance.”

Initiatives such as Women also Know History have “made this a lot easier, so it's no longer possible to say, ‘I don't know many women to follow,’” Blain added.

Rachel M. Werner, the new study's senior author and a professor of medicine at Penn, said that beyond Twitter, there is a "larger issue to address that relates to promoting and amplifying the research of women, and giving women equal due for their contributions." While following more women "would be great," she said, "it would be even better to have a more level playing field where women don’t have to work harder to have their voices heard."

There is some good news for women on Twitter. Samara Klar, an associate professor of political science at the University of Arizona, co-authored an article, currently under review, that didn't analyze Twitter followers. But it did find a positive correlation between citations and tweets about articles in political science and communication -- and no evidence that articles written by men generated more tweets than those written by women.