You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

When Will Smith was in his first year at the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology four years ago, he often got lost in the old and poorly laid-out building that housed his civil engineering classes. But whenever he couldn’t find the right room, an upperclassman would usually stop and help him -- probably because of the look of consternation on his face, but also because of the tiny green cap on his head.

The School of Mines is perhaps the only institution left in the country that still maintains the tradition of handing out freshman beanies -- a small felt hat that signifies a student's newbie status -- as a way to broadcast that the new students might need some assistance getting acclimated to the campus.

Wearing the beanie was once a ubiquitous ritual in the early 1900s, shared by students at nearly every college in the country -- from the moderately sized, selective private institutions such as Dickinson College to the large public institutions such as Ohio State University.

That the School of Mines still passes out the beanies is remarkable because the practice largely died in the early 1960s. Students wore them for their entire initial year on campus, and they had the same effect as wearing a scarlet letter. Removing the caps in public could lead to punishment by upperclassmen, the lightest sanction being a paddling. John McCool, a historian who previously worked at the University of Kansas, documented instances of first-year rebels who took off their beanies being forcibly dunked into the nearby Potter Lake. Students at some institutions were expected to tip their beanies in respect when in the presence of seniors.

These hazing practices were unsurprising given that beanies were most popular from the early 1900s to the 1950s, the “golden era” of fraternities. During that period, college life was rife with symbols representing one's importance and standing on a campus, said John R. Thelin, a professor of higher education and public policy at the University of Kentucky and author of A History of American Higher Education (Johns Hopkins University Press).

As campuses grew and became more diverse and were no longer dominated by affluent white men, such open forms of abuse largely fell out of style, Thelin said.

The shift largely began after an influx of World War II veterans on college campuses. These beneficiaries of the G.I. Bill looked at the beanies with a degree of disdain, Thelin said. They were typically older students who had little interest in following traditions, he said.

McCool wrote about how veterans on the Kansas campus refused to wear the caps, which were largely promoted by a group known as the K-Club, a collection of top campus athletes. The veterans’ intransigence “finally spoiled the tradition,” McCool wrote.

Even though the tradition persists at the School of Mines, beanies are not an invitation for upperclassmen to harass first-year students -- they are now an identifier to help newbies feel welcome.

“Even if I was in a hurry, if a freshman looked lost, I would try to stop and help them,” said Smith, who graduated in May and now is working toward a master's degree in structural engineering at the School of Mines.

The beanie tradition also creates camaraderie among the new students as they start their studies.

“It means you’re not alone in it, you always have a study buddy,” Smith said. “I still talk to people I met getting my beanie and during homecoming.”

The beanies worn at the School of Mines are green and yellow. These are not the School of Mines’ colors, but those of its rival, Black Hills State University. The logic behind wearing the rival's colors is that School of Mines’ freshmen were smarter than Black Hills’ seniors, The Rapid City Journal reported.

The beanies are made by a local chapter of the P.E.O. Sisterhood, a philanthropic organization that provides scholarships to women. First-year students receive the beanies during orientation and wear them for about a month until homecoming. During this period, the students are referred to as “frosh.” At the homecoming football game, they will do a lap around the track and then throw their beanies into the air, marking the transition into a full-fledged freshman.

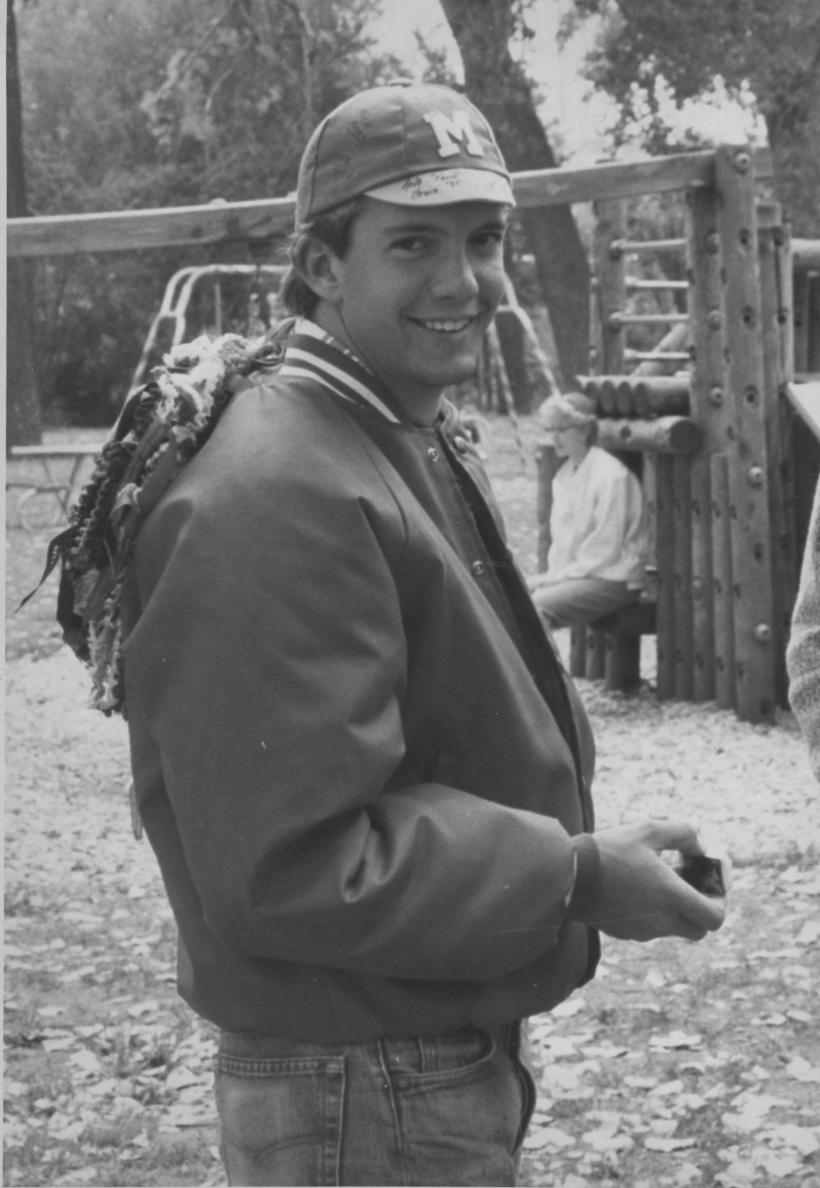

Seniors also wear a billed white hat off and on throughout the year. The seniors will often pin their freshman beanie to the back of their hats and also attach pens and markers that people use to sign the hats. At bars in Rapid City, seniors can earn special garters they can pin to the hat after drinking specific drinks.

Smith said the senior hat symbolizes surviving the School of Mines’ difficult degree programs. Most of the majors at the university are geared toward engineering and sciences and can be challenging, he said.

The concept of wearing beanies may prompt eye rolls by some people. Smith said his first-year roommate considered the beanies a bit stupid. And some students still do today, said Greg Hintgen, past president of the School of Mines’ Alumni Association. But no one forces students to participate, even though most do.

“School of Mines is just a smaller school, with a lot of traditions,” said Hintgen, who was a freshman in 1995.

When the School of Mines’ president, Jim Rankin, took over last January, he wondered whether, as a first-year president, he should wear a beanie, too.

He decided he should, but only during special events.

Rankin, a School of Mines alumnus from the Class of 1978, said although the beanies may have separated students in the past, “Now [the tradition] just brings people together.”