You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

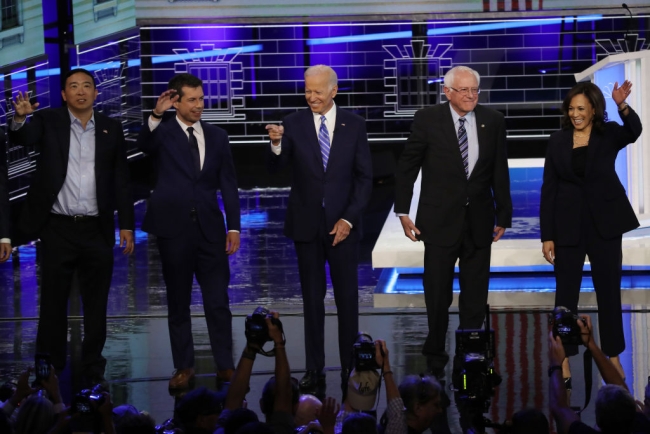

(From left) Presidential candidates Andrew Yang, Pete Buttigieg, Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders and Kamala Harris

Getty Images

Campaign proposals for broad loan forgiveness from Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders have helped make student debt a top issue in the Democratic presidential primary race.

It’s also made for as clear a dividing line as any issue between Warren and Sanders and their more moderate rivals for the 2020 nomination. Primary rivals have argued the Warren and Sanders plans are either unrealistic or unfair.

Other campaigns, though, have begun to roll out more narrow debt relief plans, including that of South Bend, Ind., mayor Pete Buttigieg, who argued at a Detroit primary debate last week that debt relief should begin with borrowers who attended for-profit colleges “that took advantage of people.” California senator Kamala Harris also released her own debt relief proposal last month targeting business owners in disadvantaged communities.

Other candidates, meanwhile, have called for simplifying loan repayment or allowing borrowers to refinance. And former San Antonio mayor Julián Castro in May called for loan forgiveness for borrowers who make long-term use of federal safety net programs. Whereas Sanders and Warren have split over how much automatic debt relief to offer borrowers -- the Warren plan would cap forgiveness at $50,000 and offer limited relief to borrowers with incomes six figures or higher -- their rivals are proposing a number of tweaks to the current system.

The variety of the proposals suggests there isn’t a moderate consensus yet on what to do about debt relief for current student borrowers, said Ben Miller, vice president for postsecondary education at the Center for American Progress.

“What the middle ground proposal is is still unknown,” he said.

Offering debt relief to for-profit college students hasn’t generated the same buzz as broad loan forgiveness. And Harris’s plan was widely lampooned on social media for what critics saw as its needless complexity. Some observers say the proposals illustrate the challenges with crafting a plan that’s both targeted to borrowers who need help the most and is straightforward to understand.

More Targeted Plans Mean More Complications

In terms of the design of debt relief proposals, the Sanders plan would be easiest to carry out, said Matt Chingos, director of the Urban Institute’s Center on Education Data and Policy.

“Congress could pass a one-sentence law saying, ‘We forgive all the debt,’” he said. “Politically, it’s obviously a different story.”

The Buttigieg and Harris proposals are targeted to provide relief to specific kinds of borrowers. A smaller debt relief plan might be easier to pass through Congress, Chingos said. But offering a plan with more narrow policy goals raises more questions about how those proposals would be crafted.

So far, both campaigns have been light on details. Neither has produced projections of how many borrowers would benefit or the cost of their debt relief programs.

Buttigieg wants to cancel the debt of borrowers who attended “low-quality” programs that failed the federal gainful-employment rule -- a regulation that Education Secretary Betsy DeVos officially repealed in June. Although he specifically cited for-profit colleges at the Democratic debate, the proposal released on his campaign website suggests borrowers who attended any program that failed the gainful-employment ratings would qualify.

Harris is proposing to cancel up to $20,000 in debt for Pell Grant recipients who open a business in a disadvantaged community and operate it for at least three years.

Neither was released as part of the respective campaigns' higher ed agendas. Instead, they were included in broader plans to address racial equity. Although full details aren't available about the plans, many borrowers who would benefit would likely be students of color.

The challenge for such highly targeted plans, Chingos said, is they have to define what specifically would meet each qualification -- for example, what counts as a business or as a disadvantaged community.

Since the fall of 2017, roughly 99 percent of applicants have been rejected for the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program, illustrating the downsides of a highly targeted debt relief program with multiple restrictions on who qualifies.

Although the Education Department hasn’t released new gainful-employment data since 2017, the Buttigieg proposal could be more straightforward to implement, Chingos said, because the federal government already has tax returns for borrowers. The federal government has also expanded the data it collects on program outcomes through the College Scorecard.

Chingos said whatever the amount of debt forgiveness a proposal offers, the government should be able to provide debt forgiveness using its own data.

“You don’t want to have a bunch of forms and paperwork, because that advantages people who know about the program and know how to navigate the process,” he said.

Are Moderate Proposals More Feasible?

Marshall Steinbaum, an assistant professor of economics at the University of Utah and a proponent of universal debt cancellation, said the more moderate debt relief plans aren’t actually more realistic. Rather, he said, they do less to challenge the assumption of policy makers that student debt is “good” debt.

“These targeted plans are predicated on picking out the most meritorious, or the most needy, or the most worthy debtors and canceling their debt, while keeping it in place for everyone else,” he said. “It’s impossible to decide who is the most deserving victim. The process of elites choosing between the deserving and undeserving is alienating as a political proposition.”

Reid Setzer, director of government affairs at the Education Trust, said the Harris and Buttigieg plans "are not quite expansive enough to tackle the extent of the problem."

Ed Trust has supported the Warren debt cancellation proposal although the group has also said the plan should take account of household wealth in addition to income.

There’s clearly pressure on presidential primary candidates to propose solutions for student debt. But Tamara Hiler, deputy director of education at the think tank Third Way, said there is an opportunity for candidates to offer proposals that direct relief to borrowers who need it the most without running into the pitfalls of Public Service Loan Forgiveness.

During the 2016 presidential primary campaign, Hillary Clinton famously proposed, like Harris, to offer student debt relief to entrepreneurs. One proposal would have allowed start-up founders with federal student loans to defer payments for three years without accruing interest. Another would have forgiven up to $17,500 for borrowers who started a business in a “distressed” community.

Not only was that plan overly complicated, Hiler said, “it also wasn’t necessarily targeted at people who needed debt forgiveness or people who needed resources the most.”

Harris and Buttigieg, she said, should get credit for thinking about who would most benefit from loan forgiveness.

“There would be implementation challenges whether you’re talking about the Warren plan, the Sanders plan or any of these more targeted plans,” Hiler said. “They are really trying to make sure the limited taxpayer funds going into these programs would be targeting students who need them the most.”

The variety of the approaches in candidates’ debt relief plans show how they understand the problem of student debt differently, Miller said. If Sanders sees student debt as an economic justice issue and Warren sees it as a racial equity issue, Buttigieg sees debt working poorly for certain kinds of borrowers.

“You’re seeing different articulations of where candidates think the problem lies,” Miller said. “People can debate which one is the most accurate.”