You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Chelsea Corkins graduated Kansas State University in August 2013 with a joint undergraduate and master’s degree in biological and agricultural engineering. Later that month she headed to Virginia Tech for a Ph.D. program in biological systems engineering.

In many ways, Corkins thrived at Virginia Tech. She liked what she was learning, had friends and took on leadership roles that eventually led to her to being elected president of the Graduate Student Assembly. But doubts about pursuing a Ph.D. were creeping in. She wasn’t enthralled with research and looked forward to teaching undergraduates and maybe even high schoolers, not graduate students.

With the support of her dean, Karen dePauw, and several faculty teaching mentors, Corkins considered options beyond the Ph.D. -- including leaving with a master’s. Because she already had a master’s in her field, though, she changed tracks a bit. After taking some time off to work in an agricultural education program through Virginia Tech, she re-enrolled as a master’s student in agricultural leadership and community education.

Corkins graduated this year and is now working as a community engagement specialist in agricultural extension at the University of Missouri.

All told, Corkins took six years to get that second master's. But she doesn’t regret it -- or her choice to leave her Ph.D. program. She’s convinced that experiences she gained during and between her studies landed her the position she holds today.

“There is no required timeline for graduate school. And beginning a Ph.D. program should not require that you finish that program,” she said. “Many students are still very young and exploring what they like to do. You’re not signing your soul away when you sign up for a program. Those five or so years aren’t set in stone, and there’s a reason for that.”

She added, “You’re not indebted to anyone. It’s all part of the experience.”

That said, Corkins didn’t take her decision lightly, and says she could not have made it without the help of mentors. Without them, she might even have walked away from her time at Virginia Tech with no degree.

Others students complete their programs with few to no doubts. But Corkins said she still encourages current Ph.D. candidates to check in with themselves on a regular basis, starting early on. What are their career goals, have they changed of late and is a doctorate still compatible with them? How are students feeling about graduate school -- and life in general?

A Pivot

Corkins’s choice is one way to “master out” of a Ph.D. program, although she prefers the term “pivot.” More typically, “master out” is used to describe students who enroll in a Ph.D. program and exit with a master’s degree in that same field instead.

It’s unclear how often this happens. Over all, 50 percent of Ph.D. students don't finish their programs. But there is no national data on how many master out, as opposed to just leave, and institutions don’t typically track this path. But it probably happens more than we think. And those who have done it say it should be a more visible choice.

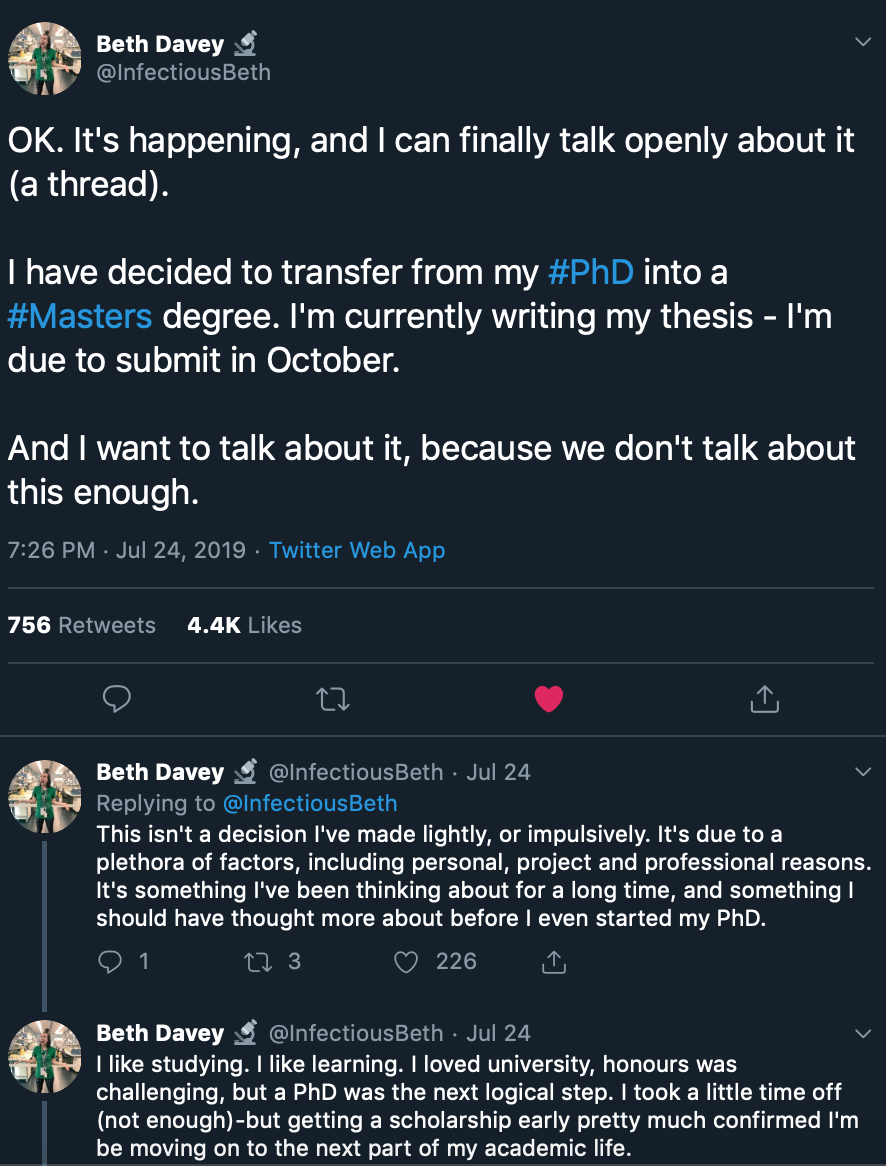

Beth Davey, a graduate student working at Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Australia, recently announced her decision to master out on Twitter. In a popular thread, she described a cycle of doubt about whether she wanted, needed or even deserved a Ph.D. Ultimately a friend’s decision to master out of a graduate program was the confirmation she needed that doing so was OK. That she would be OK.

“The response was overall really positive,” Davey told Inside Higher Ed, “but I have had moments of colleagues in particular thinking I would change my mind, or thinking I am throwing away my Ph.D. opportunity. I also had some guilt within myself for a long time” but “finally decided that if I did want to do a Ph.D. again down the track, I could -- and I’m sure I’d be a lot happier and wiser about deciding.”

“The response was overall really positive,” Davey told Inside Higher Ed, “but I have had moments of colleagues in particular thinking I would change my mind, or thinking I am throwing away my Ph.D. opportunity. I also had some guilt within myself for a long time” but “finally decided that if I did want to do a Ph.D. again down the track, I could -- and I’m sure I’d be a lot happier and wiser about deciding.”She added, “I also believe I rushed into my Ph.D., as it was the next logical step for me in academia, and I didn’t really know what else to do with my honors degree aside from a higher degree,” or working as a research assistant or technician, which she did for nine months.

Davey needs to finish her thesis to receive her master’s. She’s unsure about her exact career goals but hopeful she’ll be in a better place to contemplate them following graduation. Still, while she’s writing, she’s reaching out to her various networks and talking to people working in research, but not necessarily as researchers -- think project management, science communication and education. She also works at a science education center for K-12 students.

Suzanne Ortega, president of the Council of Graduate Schools, said there are multiple reasons that doctoral students leave with a master's, including family and life circumstances, “evolving career objectives, and a recognition that the master’s degree offers appealing options.”

Chris Golde, assistant director of career communities for doctoral students and postdoctoral fellows at Stanford University (and a columnist for Inside Higher Ed), said a Ph.D. is a “very long commitment that’s not for everyone.” People can lose enthusiasm and “any number of things that happen in life can happen along the way.”

Still, students’ identities often became wrapped up in their Ph.D. goals, and some who might want to leave with a master’s don’t consider it (Golde doesn’t like the term "mastering out," either) because “any choice that’s not very visible is a harder one to make.”

Not a ‘Consolation Prize’

Yet Ortega said that exiting a doctoral program with a master’s degree “can be a very successful outcome, and one the higher education community should accept and support.” Regardless of why they leave, “students should know their degree is valued and can opens doors to additional career pathways and advancement.”

Jerry B. Weinberg, associate provost for research and dean of the Graduate School at Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville, said that the master’s degree is no longer the “consolation prize” for opting out of the doctoral track, but rather a “sought-after degree by employers in quite a few fields of practice.”

In many fields, such as natural science, technology, engineering, math and health care, he said, employers see the master’s degree as the “expected or preferred level of entry.” The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that employment in master’s-level occupations is projected to grow by almost 17 percent between 2016 and 2026, the fastest of any education level, Weinberg noted. And many recent employees without a master’s are returning to school as “a pathway to promotion and raises.”

Weinberg also said that Council of Graduate Schools data show how master’s degree applications and conferrals have increased continually over the last 10 years, with significant gains in the last five. About 84 percent of all graduate degrees conferred are at the master’s level, and institutions have changed the way they deliver programs to meet the needs of all students.

Instead of “mastering out,” Weinberg said it would be more accurate to say that students are mastering “in,” due to the increased demand.

Leonard Cassuto, professor of English at Fordham University who has written about and long advocated changing graduate education to focus on students, said a candidate’s decision to master out (or in) should never come as a total surprise to a department. Students should feel comfortable exploring their various degree and career options with their faculty mentors. And when they don’t, he said, the department has failed -- not the student.

Such conversations and decisions are better made earlier rather than later, Cassuto also said. It’s only natural for some students to decide, through a few years of graduate exploration, that a Ph.D. is not for them. But students leaving well into their research programs because that kind of work isn't for them also signals institutional failure, he said.

Centering Students

“Graduate education has centered on the Ph.D. since its inception, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing, as the Ph.D. can provide an organizing principle,” Cassuto said. “But as a professional institution, we haven’t done very much to think beyond the Ph.D., or people who don’t necessarily need it but are in graduate school anyway.”

In today’s academic job market and overall climate, in particular, he added, “no one can afford that kind of indifference.”

Golde, at Stanford, said students don’t necessarily need to share all their doubts with their faculty mentors and advisers, but rather explore them with someone. That’s why institutions need to develop infrastructures to support graduate students, including career centers and mental health facilities. Pre-existing anxiety and depression can make gradate school harder, she said, and can sometimes surface in graduate school.

Unfortunately, she said, many institutions are still playing catch-up when it comes to supporting graduate students in multiple ways, as they do undergraduates.

Master’s degrees are typically not conferred automatically. In Cassuto’s department, for example, Ph.D. students who enter without a master’s become eligible to get one after they pass their comps. But they have to formally request it from the graduate school.

At Stanford, Golde recommends that all Ph.D. students complete the paperwork and other necessary steps to get a master's for this reason -- what she joked was “credit for time served.”

At Virginia Tech, the master’s isn’t automatic, either. But dePauw, the dean who mentored Corkins, said the university accommodates students who decide they want to leave with a master’s instead of a Ph.D., such as by allowing them to stay on to complete any necessary requirements.

Some institutions, including Virginia Tech, have worked to provide the kind of infrastructure Golde mentioned and to promote cultural change. DePauw helped developed the Transformative Graduate Education initiative, which includes programs and courses that transcend departments and promote inclusion, interdisciplinarity and community. The campus also has a Graduate Life Center that houses courses, programs and events, administrative offices, and even graduate student apartments.

Still, dePauw said, there’s more work to be done to change graduate education and the way it influences students’ paths.

“Underlying some of these things is impostor syndrome and the personal angst and stress that goes on. Some people will kind of stick it out and persevere, but my philosophy about graduate education is that we should be thriving, not surviving,” she said. “We need to get these things out in the open and talk about them -- perfectionism and stress and work-life balance, and do more to make all of it easier. We have to change the culture of graduate education.”