You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

WASHINGTON -- With the number of refugees at a record high, what should colleges and universities do to give opportunity to forcibly displaced people whose prior educational qualifications are undocumented or unverifiable?

Speakers here at the annual NAFSA: Association of International Educators conference presented Tuesday about programs in place to recognize credentials from refugees in Europe and Canada as well as more nascent efforts to encourage more flexible admission policies for refugees and other people in refugee-like situations in the U.S. The United Nations High Commission on Refugees estimates that there are 68.5 million forcibly displaced people worldwide, representing the highest level of displacement on record.

“Recognition is the key to empowerment, is the key to inclusion and the key to preventing exclusion from the society,” said Marina Malgina, the head of the section for interview-based procedures at the Norwegian Agency for Quality Assurance in Education.

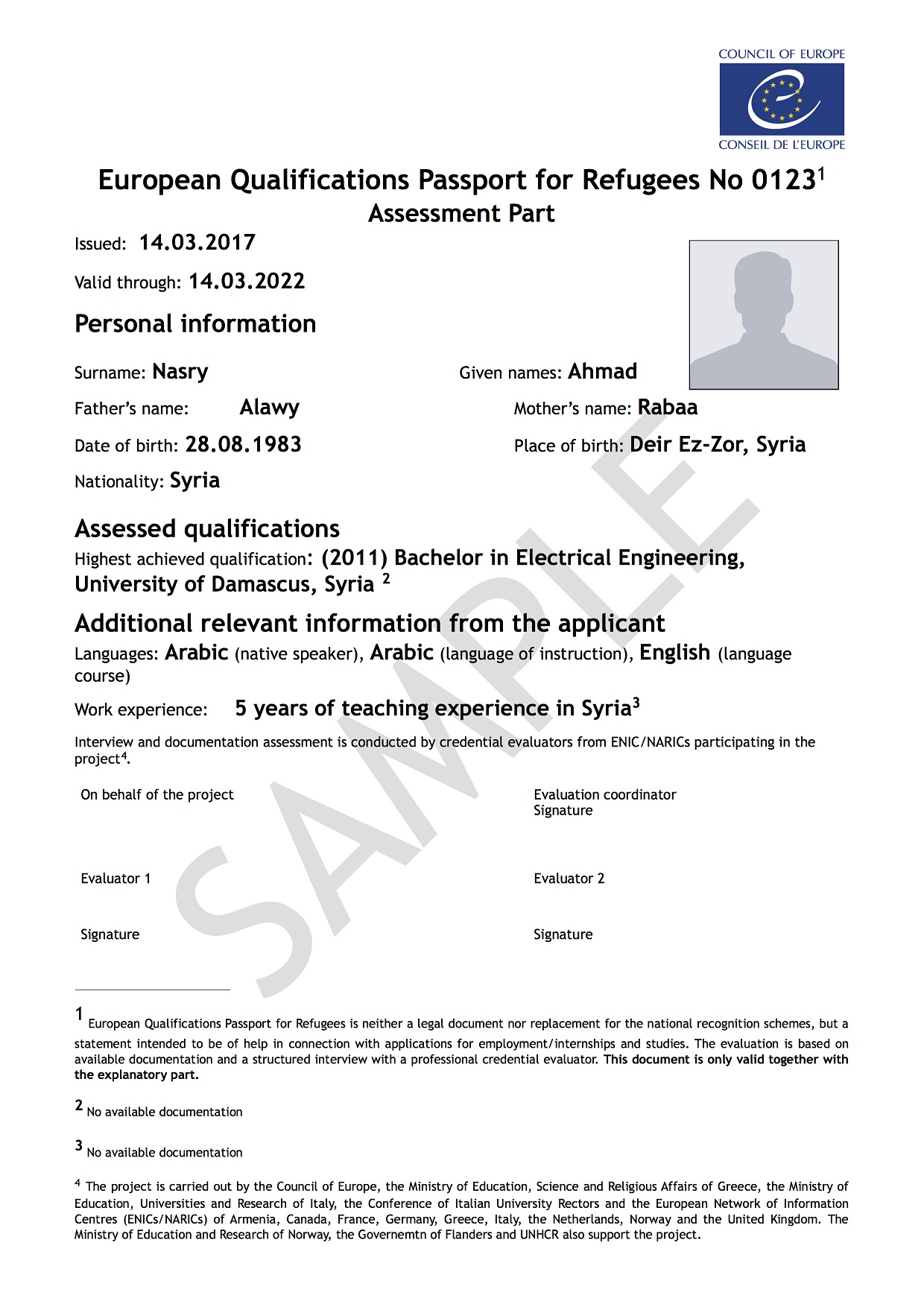

Malgina presented on the European Qualifications Passport for Refugees, a multinational, Council of Europe-led initiative that involves an assessment of higher education qualifications based on an analysis of available documentation by professional credential evaluators and an interview.

The resulting document, or “passport” -- a sample of which is at right -- “explains the qualifications a refugee is likely to have based on the available evidence,” according to an information sheet on the council’s website. “Although this document does not constitute a formal recognition act, it summarizes and presents available information on the applicant’s educational level, work experience and language proficiency. The evaluation methodology is a combination of an assessment of available documentation, the considerable experience gained through previous evaluations and the use of a structured interview. Thus, the document provides credible information that can be relevant in connection with applications for employment, internships, qualification courses and admission to studies.”

The resulting document, or “passport” -- a sample of which is at right -- “explains the qualifications a refugee is likely to have based on the available evidence,” according to an information sheet on the council’s website. “Although this document does not constitute a formal recognition act, it summarizes and presents available information on the applicant’s educational level, work experience and language proficiency. The evaluation methodology is a combination of an assessment of available documentation, the considerable experience gained through previous evaluations and the use of a structured interview. Thus, the document provides credible information that can be relevant in connection with applications for employment, internships, qualification courses and admission to studies.”

Kevin Kamal, the associate director of institutional relations at the Canadian office of World Education Services, a nonprofit organization that evaluates academic credentials, described a similar project in Canada.

Canada has since 2015 experienced a sizable increase in the number of refugees, in particular coming from Syria. The challenge, Kamal said, is how individuals who only have partial or unverifiable academic documents from their home countries can prove their educational qualifications.

“How these individuals are going to receive recognition for their academic achievements, that remains a big challenge,” he said. “When we are talking about recognition we are really talking about access, access to employment, both in regulated and nonregulated occupations, and access to higher education.”

Kamal presented on what's known as the WES Gateway Program. Qualifying refugees are referred to the program through one of 13 partner organizations, two of which are licensing agencies and 11 of which are refugee resettlement agencies. To participate refugees must have at least one officially issued document, such as an academic transcript, degree certificate or professional license. WES then seeks evidence to corroborate the document based on documents in its archive and issues an evaluation report.

In the pilot phase involving 337 Syrian refugees, a significant number of Canadian institutions -- both community colleges and universities -- proved willing to accept WES’s evaluation of an unauthenticated credential. According to Kamal, 42 percent of those participating said they used WES’s evaluation for higher education purposes. Of that 42 percent, 71 percent said they received an offer of admission from a Canadian college or university. Kamal said a number of licensing agencies accept the documentation as well. WES Canada has now expanded the program beyond Syria to also include refugees from Afghanistan, Eritrea, Iraq, Turkey, Ukraine and Venezuela, and the program is now being tested on a smaller scale in the U.S.

“One of the challenges when it comes to credential recognition for refugees is clearly just the acceptance of it,” said Bryce Loo, the research manager for WES in the U.S. “A lot of work that we’ve had to do in Canada is working on building partnerships, building recognition: Is this something that will be used?”

The U.S. unlike Canada, has scaled back its admission of refugees over the last several years. As for the credential evaluation challenge, Loo said, "My general assessment is more has been happening in Europe and Canada relative to the U.S., but there is movement happening in the U.S." He noted several groups that are working on this issue, including an organization that was established last year, the University Alliance for Refugees and At-Risk Migrants.

The American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers published a policy paper earlier this spring, "Inclusive Admissions Policies for Displaced and Vulnerable Students." The paper includes a practical guide for credential evaluation for institutions working with applicants who have unverifiable or incomplete academic documents due to forced displacement (Loo is one of the co-authors of the guide).

The guide provides a list of documents that can be requested as supplemental corroborating evidence as well as a list of additional steps colleges can take in assessing an applicant's background and content knowledge, including examinations or standardized testing requirements, assessment of skills, interviews by professors, completion of a special project or paper, submission of a portfolio or sample work, and the utilization of prior learning assessment frameworks more typically used to give adults returning to college credit for their prior work experience. It also includes a checklist for universities to follow to ensure they have the appropriate expertise and resources to conduct an evaluation, and discusses the option of working with a third-party credential evaluation service.

The AACRAO report notes that refugees may not be able to access official credentials from their previous institutions for a variety of reasons: colleges and universities in conflict zones may have closed or stopped functioning, or even if they are functioning they might refuse to issue a document to a student for any number of reasons, including political motivations. The report notes as well that some applicants "may have good reasons for not requesting their credentials from institutions or ministries of education (which can be agents of the local government) for fear of retribution to themselves or their loved ones who are still in the country. Many young Syrian men, for example, have fled that country to avoid mandatory military service to the [Bashar al-]Assad regime. By requesting documents be delivered to an institution abroad, these young men will expose that they fled the country and thus avoided their military service, putting family and friends on the ground still in Syria potentially in jeopardy."