You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Jennifer Freyd, professor of psychology at the University of Oregon, has spent years studying the concept of institutional betrayal, including when institutions don’t help right the wrongs committed within them.

Now Freyd is battling her own institution in court. She alleges that Oregon failed to properly respond to what her own department chair called a “glaring” pay gap between Freyd and the men she works with -- $18,000 less than that of her male peer closest in rank.

The case was just dismissed by a federal judge who said that the pay difference was more about the kind of work the men in her department do and the retention raises they’d secured over the years. But research suggests that even these explanations are rooted in issues of gender. Freyd has already filed a notice of intent to appeal.

“I was very caught off guard by this outcome,” she said recently of the dismissal. “But I’ll pursue this as long as I can. It’s important to know that this isn’t really what I want to be doing right now -- I have a wonderful new project on institutional courage. But I have a responsibility here.”

And not just to herself, as Freyd wrote in a court filing late last year.

“As someone who has reached a certain level of professional achievement, I feel a sense of responsibility to speak the truth of my experience,” she said then. “The pay inequity I have experienced is very painful, and I do not want the women I have mentored, my current and many former graduate students, my own daughter in graduate school, or the junior faculty we have hired in the department of psychology to go through what I’ve gone through.”

Oregon, meanwhile, said in a statement that Freyd is “a respected and valued” member of the faculty, “and we believe this decision establishes that she is fairly compensated relative to her peers.” The university believes the court “correctly decided the case” and will continue to defend itself on appeal.

Losing $500K Over a Lifetime

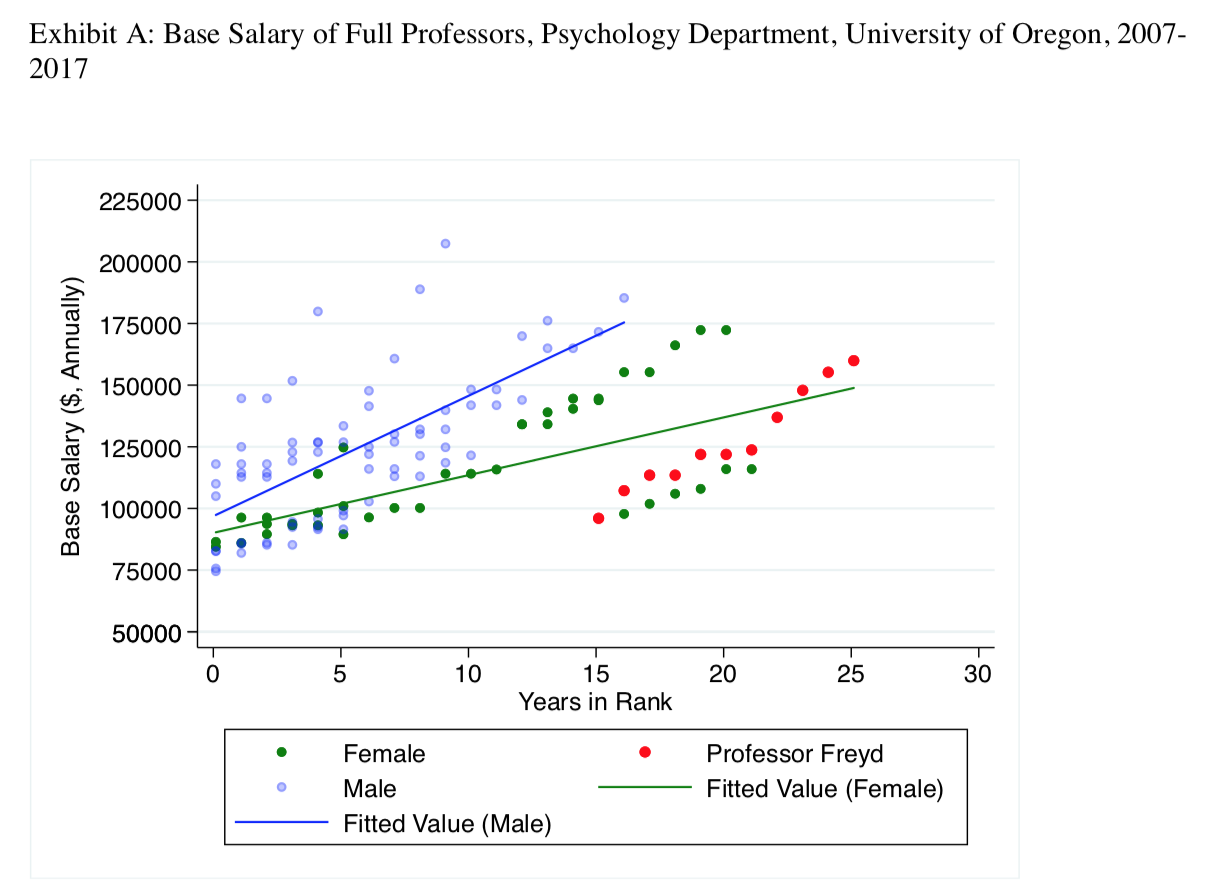

According to Freyd’s original complaint, salaries in her department are supposed to be determined by seniority and merit. Merit-based raises are awarded based on a consideration of research, teaching and service. Oregon’s psychology program conducted a self-study in 2016. One of the findings was that psychology faced a “significant equity problem with respect to salaries at the full professor level.” The authors conducted a regression analysis and found that the annual average difference between male and female full professors was about $25,000. So over a period of 20 years, women would receive approximately $500,000 less than their male counterparts, and probably even more, when considering retirement benefits, which are based on salaries.

The department also conducted an external review of the department. That committee of outside professors also noted the “gender disparity in faculty salaries at the full professor level” and recommended that the department “continue pressing for gender equity in terms of pay at the senior levels of the faculty.”

Both reviews traced the disparity back to retention raises given to professors who pursued outside offers. The self-study noted that this was concerning, as “it is not obvious that the frequency of retention negotiations is a strong indicator of overall productivity.” Rather, it said, “there is strong evidence of a gender bias in both the availability of outside offers and the ability to respond aggressively to such offers.” The outside review said it’s “widely recognized that there is a difference between the genders in terms of seeking outside offers, and if this holds at Oregon, then the bias does have a gender basis.”

A ‘Most Glaring’ Case

The department sought ways the rectify the issue throughout 2016, such as by using funds available for raises.

Freyd’s deans were made aware of the issue and even acknowledged that it was a problem in conversations with the department, she said. But the psychology faculty was told there was nothing to be done.

Ulrich Mayr, department chair, continued to pursue the issue. He wrote in a late 2016 memo to Hal Sadofsky, associate dean of natural sciences in the College of Arts and Sciences, and Andrew Marcus, dean of the college, that when controlling for years in rank, the department’s male full professors earn on average $30,000 more than women. The difference is “remarkably stable” across recent years, even with major faculty departures, and doesn’t change when taking out the department’s highest-paid full professor as an outlier or when controlling for h-index (a research impact factor) or 2016 merit ratings, he said.

“This imbalance is difficult to ignore, in particular when considering lifetime cumulative effects. It is a threat to overall morale, not only among full professors, but also among early and midcareer female professors who wonder how they can escape the same fate as their senior colleagues,” Mayr wrote.

While this dynamic could make it harder to offer professors strong counteroffers in retention matters going forward, he said, “Aggressive retention activity should not be the only way to maintain a market-adequate salary, in particular as there are structural differences and actual biases that make it harder for women to participate in these activities.” He noted that the majority of female full professors haven’t participated in recent retention negotiations, and that two “highly meritorious” male full professors appear to have relatively low salaries for the same reason.

Beyond general trends, Mayr urged “immediate” action on the “most glaring inequity case” -- Freyd’s.

“Freyd is currently the most senior faculty member in the department. She is a widely recognized leader in her field with impact beyond the academy,” Mayr wrote. Yet her salary is “$18,000 less than that of her male peer closest in rank (who is still seven years her junior). When taking in consideration impact or merit, this difference further increases to $40-50,000.”

Mayr said that the department last reviewed Freyd in 2014-15 and would have advocated giving her more than an 8 percent raise if he’d known that was possible. Apparently he could have asked for more, he said he learned later.

“Given the inequity she has experienced up to this point, I believe she should not be punished for my lack of information,” Mayr wrote, asking for a 12 percent raise to bring Freyd’s pay to parity with the next-highest-paid male full professor. “But even a fraction of this, say 5-6 percent, would help mitigate the gap and make it more realistic that we could finish the job with a future round of equity raises.”

Freyd’s college announced raises in early 2017. She received no additional salary increase beyond the standard across-the-board and merit raises. She says that Marcus and Sadofsky, the deans, asked to meet with her and told her that wouldn’t address her gender-equity concerns with respect to pay. “Only” three men were paid more than she was in her department, she recalls them saying.

There are six male full professors in her department, according to Freyd’s complaint. All are junior to her in years of service, and none has a higher h-index than she has. She is paid nearly the same as a fourth male colleague who is substantially junior.

Freyd sued Oregon for sex discrimination, including under the Equal Pay Act and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which prohibit sex discrimination. She’s seeking an “appropriate” pay raise, back pay and damages.

Support Along the Way

Freyd received support from colleagues, students and other experts along the way.

“In addressing gender discrimination, you have indirectly given much to us graduate students,” reads an open letter signed by dozens of graduate students. “Not the least of which is hope. Hope for a life in which such discrimination is a thing of the past. And hope that we, in our own ways, can fight for equality in all forms for ourselves and our colleagues.”

Jennifer Gomez, a psychology Ph.D. who studied under Freyd, wrote in an open essay that her lawsuit highlights Oregon as a “shameful example of the rampant gender discrimination currently in practice across universities, including explaining away women’s lower pay through grant funding, retention efforts and tokenism.”

Kevin Cahill, a research economist at the Center on Aging and Work at Boston College, for example, wrote in a declaration to the court that his regression analysis of departmental salaries found that women’s salaries by years in rank “fell far below that for male faculty, and the discrepancy increased” over time.

Source: Cahill

Cahill attributed the trend to retention raises. And the earlier departmental studies noted that this factor is in itself gendered. Gomez said so, too. Is it?

One 2006 study found that gender differences in the propensity to initiate negotiations may be explained by differential treatment of men and women when they attempt to negotiate. Participants who evaluated written accounts of candidates who did or did not initiate negotiations for higher compensation penalized female candidates more than male candidates for initiating negotiations.

In another experiment in that same study, participants evaluated videotapes of candidates who accepted compensation offers or initiated negotiations. Male evaluators penalized female candidates more than male candidates for initiating negotiations, with perceptions of niceness and being demanding, explaining resistance to female negotiators. (Female evaluators penalized all candidates for initiating negotiations.) The study also found that with male evaluators, women were less inclined than men to negotiate, and “nervousness” explained this effect. There was no gender difference when the evaluator was female.

‘Counteroffer Culture’?

More recently, last year, the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education, based at Harvard University, published some findings of its first national Faculty Retention and Exit Survey.

Insights into the negotiation process suggest “some troubling gender bias,” the collaborative’s staff wrote at the time. “For example, among those who didn’t ask for a counteroffer, men are more likely than women to receive one, anyway; among those who do ask for a counteroffer, women are more likely to be denied.”

Moreover, the staff wrote, “Higher education's ‘counteroffer culture’ has real costs. Faculty are expected to cultivate outside offers before they can ask for a better deal at home. This requirement pushes them out the door: we are finding that nearly one in three faculty who left had originally sought the offer only to renegotiate the terms of their employment.”

Cornell University did try to get Freyd to stay working then when she left it for Oregon, decades ago.

Equal Pay for ‘Equal Work’ Only

Despite that evidence, Michael McShane, the federal judge in Oregon who decided Freyd’s case, found her claims uncompelling and sided with the university against her. McShane said that unlike elementary school teachers, all professors do not in fact perform the same work, and that their pay rightfully reflects that. Put another way, equal pay for equal work only means someone when the work is mostly the same for everyone.

One of four male full professors who are paid more than Freyd -- Mayr -- was the department head who performed both financial and supervisory work, the judge said. Another served as the department’s director of clinical training and led the campus’s Center on Diversity and Community. And while Freyd received one award of federal research funding, for $25,000, from 2008 to 2018, another full professor received 34 awards of federal funding for more than $12 million. (Freyd has still authored dozens of research articles.)

By “choosing to pursue optional roles, such as acting as the principal investigator of a federally funded research grant, directing a center of research, or serving as department head, full professors change their job duties and increase the amount of responsibility that their role requires,” he wrote in his opinion. “The university does not mandate that full professors take on these additional responsibilities, but it recognizes professors' freedom to do so and to ‘remake their job’ into what they want to do, whether through outside funding or community roles.”

All that aside, however, McShane said that offering retention raises to faculty who are being recruited by other universities is “justified by business necessity.”

Oregon “must retain its faculty who are being recruited by other institutions, especially those who secure federal funding, because they help the university to maintain its status as a top-tier research institution, expand its research footprint and provide funding for the training of graduate students,” he added.

McShane also said that Freyd hasn’t provided “any specific suggestions for how to create a system in which professors would be compensated solely on the basis of their time in rank that would address retention issues.”

Freyd can’t “have it both ways,” or “brush aside” other full professors in the department earning less while sweeping in those psychology professors making more, he said.

Again, Freyd never expected the outcome, which she said reveals a misunderstanding of faculty work. She expressed concern about how the idea that professors do different work and get compensated for it differently than their peers could chill academic freedom.

Mayr, the chair, agreed, reportedly sending the psychology faculty an email saying “that given the pay structure among full professors in our department, Jennifer deserves a higher salary,” and that work needs to be done toward pay equity in the department.

The lawsuit “has no bearing on the broader question whether there are factors in society, academia and our institution that lead to gender inequities in pay, or access to other important resources,” he wrote. So these “outcomes cannot be an excuse for reducing our efforts towards identifying and counteracting such factors.”