You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

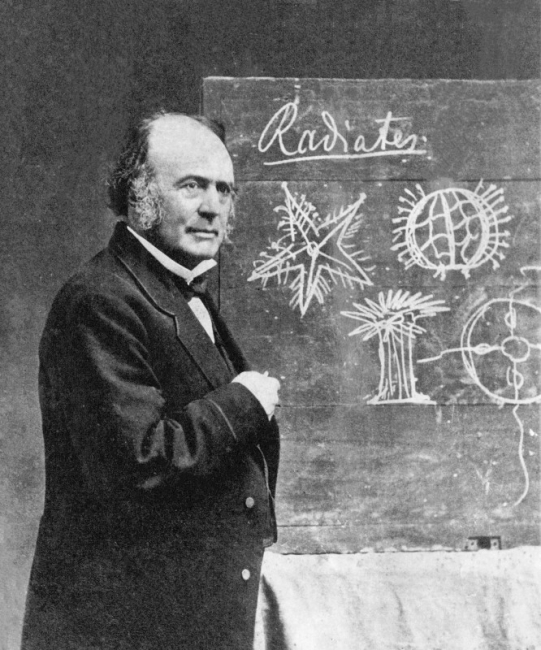

Louis Agassiz

Wikipedia

The website of Harvard University's Museum of Comparative Zoology describes its founder as "a great systematist, paleontologist and renowned teacher of natural history." The founder was the 19th-century biologist Louis Agassiz, whose scientific career started in Europe and led him to Harvard. For generations he was hailed for his contributions to science, and he still is at the museum he founded.

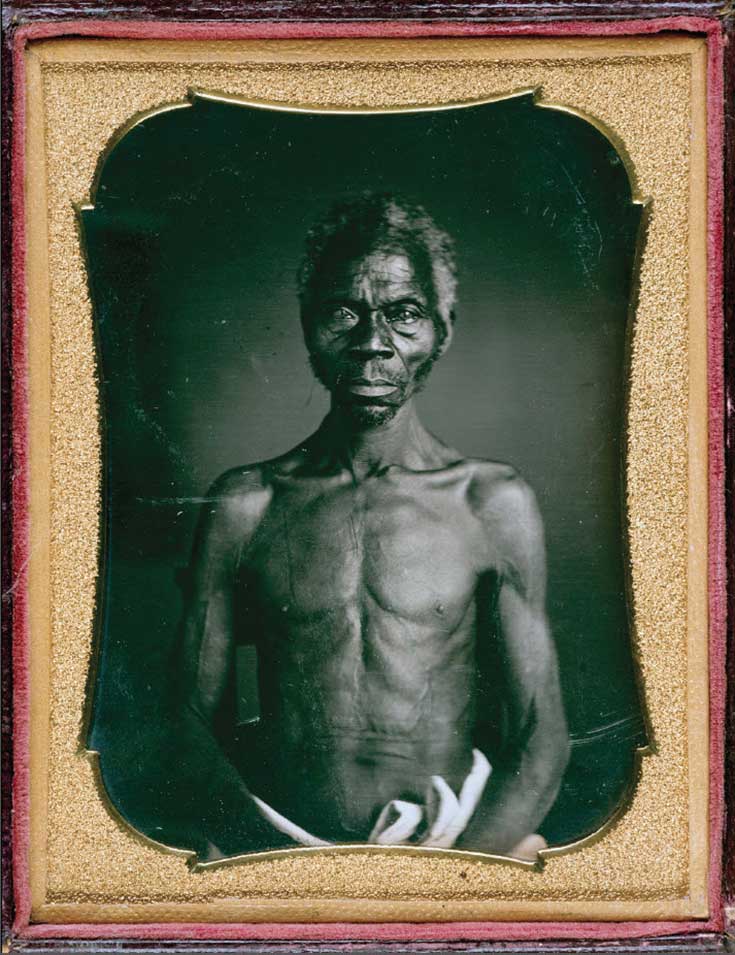

A lawsuit filed Wednesday in Massachusetts court takes Harvard to task for that continued praise, and for specific actions taken by Agassiz before and after the abolition of slavery. Tamara Lanier filed the suit; she says that she is descended from two of the slaves depicted in 1850 daguerreotypes (an early form of photography) commissioned by Agassiz.

A lawsuit filed Wednesday in Massachusetts court takes Harvard to task for that continued praise, and for specific actions taken by Agassiz before and after the abolition of slavery. Tamara Lanier filed the suit; she says that she is descended from two of the slaves depicted in 1850 daguerreotypes (an early form of photography) commissioned by Agassiz.

The daguerreotypes were lost after Agassiz died, but Harvard found them in 1977. Since then, the university has made use of them in various ways, such as this cover for a book published by Harvard University Press. One of the images, of an enslaved man named Renty, is on the left.

Lanier's lawsuit said that Harvard should turn over the images to her, pay her damages for the way it has profited from the images and take other acts to acknowledge and condemn Agassiz's racism. The lawsuit says that Harvard officials rebuffed Lanier in her attempts to talk about the issues involved and to seek justice for her long-dead family members.

Harvard declined to comment on the suit, saying that it has not yet been served with papers. The university has in recent years said that it is important for all universities to consider their ties to slavery. Harvard held a conference on the topic in 2017. Drew Gilpin Faust, then the president of Harvard, encouraged the university to study and acknowledge the role of slavery at the institution.

"Harvard was directly complicit in America’s system of racial bondage from the college’s earliest days in the 17th century until slavery in Massachusetts ended in 1783, and Harvard continued to be indirectly involved through extensive financial and other ties to the slave South up to the time of emancipation. This is our history and our legacy, one we must fully acknowledge and understand in order to truly move beyond the painful injustices at its core," Faust said in 2016.

But the lawsuit says Harvard has never done that. The suit notes that Agassiz didn't seek the photographs to document the injustice of slavery, but rather as "part of his quest to 'prove' black people's inherent biological inferiority, and thereby justify their subjugation, exploitation and segregation." And indeed Agassiz's work was used not only in the era of slavery, but after.

The enslaved people in the photographs were given no choice in the matter, the suit says. They "were stripped naked and forced to pose for the daguerreotypes without consent, dignity or compensation."

Harvard has "never reckoned with that grotesque chapter in its history, let alone atoned for it," the suit says. Since the photographs were discovered again in the 1970s, they have been used "to sanitize the history of the images and exploit them for prestige and profit."

The suit says that it is "unconscionable that Harvard will not allow Ms. Lanier to, at long last, bring Renty and Delia [also in the images] home."

Beyond Lanier's claims about Harvard, the suit raises questions about the way prominent public figures of the past, who held and promoted racist views, are seen today.

Christoph Irmscher, a professor of English at Indiana University at Bloomington, is the author of a biography of Agassiz, Louis Agassiz: Creator of American Science.

Via email, Irmscher said that one today cannot separate the racism of Agassiz "from his science, in the sense that one could comfortably say, 'Well, he had some unfortunate views, but he was the first to describe the nervous system of a jellyfish, and that’s what matters.' I do think no one writing about Agassiz today does so without acknowledging how contaminated his science is. Having said that, I would again take issue with the very idea of contamination -- while his methods might have been progressive for his time (he was a pioneer of scientific fieldwork, for example), his science itself was deeply conservative, paternalistic, an evocation of a world in which everything had been planned and things stayed in their assigned places. Which is why he became one of Darwin’s favorite targets."

The problem with some of today's criticism of Agassiz, he said, is that it is too narrow. "I do sometimes worry about the extent to which a single-minded focus on Agassiz obscures the degree to which his ideas were shared and even inspired by his contemporaries, many of whom we continue to cherish. In my book, I have made an attempt to contextualize them. For example, I quote a statement made by Ralph Waldo Emerson in his journal, written precisely after Agassiz had shared his racial views with him, that the Harvard scientist was a 'man to be thankful for.' None of Agassiz’s noxious racial views -- which have been widely known and discussed since Stephen Jay Gould’s devastating account in The Mismeasure of Man (1981) -- were, alas, original to him, although that doesn’t, of course, diminish the impact they had."