You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

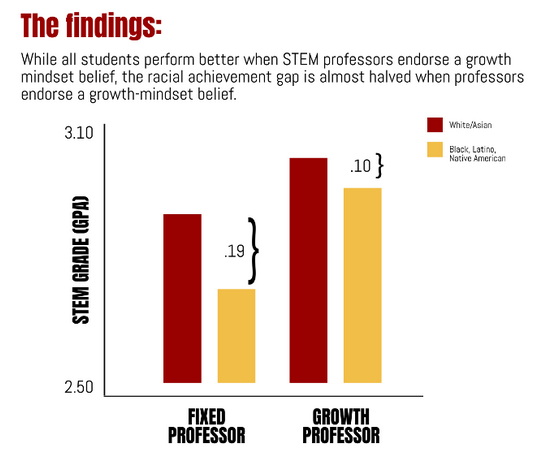

A new study suggests that faculty members' attitudes about intelligence can have a major impact on the success of students in science, mathematics and technology courses. Students see more achievement when their instructors believe in a "growth mind-set" about intelligence than they do learning from those who believe intelligence is fixed. The impact was found across all student groups but was most pronounced among minority students.

The study -- by brain science scholars at Indiana University at Bloomington -- was published in the journal Science Advances and presented last week at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The researchers collected data on 150 faculty members in a range of STEM disciplines and 15,000 students over two years at a large public research university that is not identified. Faculty members were asked to respond to a general statement about intelligence along the lines of "To be honest, students have a certain amount of intelligence, and they really can’t do much to change it."

The study then looked at student performance in courses taught by those who agreed with that perspective and those who did not.

Students from all groups earned higher grades with faculty members who thought it was possible for people to experience intelligence growth. But the impact was particularly notable for black, Latino and Native American students (see bar chart at right).

Students from all groups earned higher grades with faculty members who thought it was possible for people to experience intelligence growth. But the impact was particularly notable for black, Latino and Native American students (see bar chart at right).

The article argues that the faculty attitudes about intelligence carry over into the messages faculty members send to students, with those who believe in fixed intelligence suggesting to students that only the "innately gifted" are likely to succeed. Those who believe in intelligence growth are more likely, the article says, to share techniques with students on how they can become better learners.

Students with the latter group of faculty members are more likely to report that they are motivated to do their best work, and to recommend the course to others.

The researchers wanted to find out for the study whether some types of professors were more likely than others to hold fixed views of intelligence. But here the study didn't find patterns, even after looking for them within STEM disciplines and comparing professors by gender, race, generation or years of teaching experience.

Some studies have found that underrepresented minority students do better in courses taught by "same-race role models." But this study did not find that impact, even though it found a substantial impact on minority student performance based on attitudes about intelligence.

The paper acknowledges that there could be another factor at play. "It is possible that faculty who endorse fixed mind-set beliefs create more demanding courses -- requiring students to spend more time studying and preparing for their course," the paper says. "If this is true, then differences in students’ performance and psychological experiences might be explained by the demands of these courses (instead of professors’ mind-set beliefs)."

But the paper said that the researchers could not measure this. But they could identify the use -- by faculty members not holding to the view of fixed intelligence -- of a range of pedagogical techniques linked to improved learning by students in all groups.

Why would this divide based on views of intelligence have more of an impact on underrepresented minority students?

"Faculty beliefs about which students 'have' ability in STEM might constitute a greater barrier for [underrepresented minority] students because fixed mind-set beliefs may make group ability stereotypes salient, creating a context of stereotype threat," the paper says. "Recent research suggests that when stigmatized students expect to be stereotyped by fixed mind-set institutions, they experience less belonging, less trust and more anxiety and become less interested (27, 28), suggesting that fixed mind-set faculty might also engender these adverse outcomes among students."

Taken as a whole, the paper argues that its findings may suggest a different approach to those seeking to promote more success of all students, and especially of minority students, in STEM.

"Millions of dollars in federal funding have been earmarked for student-centered initiatives and interventions that combat inequality in higher education and expand the STEM pipeline. Rather than putting the burden on students and rigid structural factors, our work shines a spotlight on faculty and how their beliefs relate to the underperformance of stigmatized students in their STEM classes," the paper says. "Faculty-centered interventions may have the unprecedented potential to change STEM culture from a fixed mind-set culture of genius to a growth mind-set culture of development while narrowing STEM racial achievement gaps at scale."

The principal investigator on the project is Mary Murphy, a professor of psychological and brain sciences at Indiana. The other authors are Elizabeth Canning, a postdoctoral researcher in Murphy's lab; Dorainne Green, a postdoctoral researcher at IU; and Katherine Muenks, who was a postdoctoral researcher at IU at the time of the study.