You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Most community colleges are aware of the challenges students face if they are working, raising children or struggling to afford textbooks. But a newly released survey digs into the nuances of those challenges so colleges can pinpoint ways to lift barriers to college completion and prevent students from dropping out.

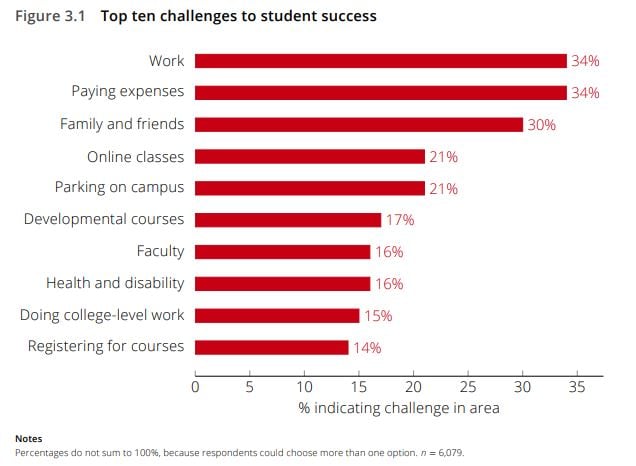

Researchers at North Carolina State University designed and encouraged students to participate in the Revealing Institutional Strengths and Challenges survey. The survey found that working and paying for expenses were the top two challenges community college students said impeded their academic success. The researchers surveyed nearly 6,000 two-year college students from 10 community colleges in California, Michigan, Nebraska, North Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Virginia, Wisconsin and Wyoming in fall 2017 and 2018.

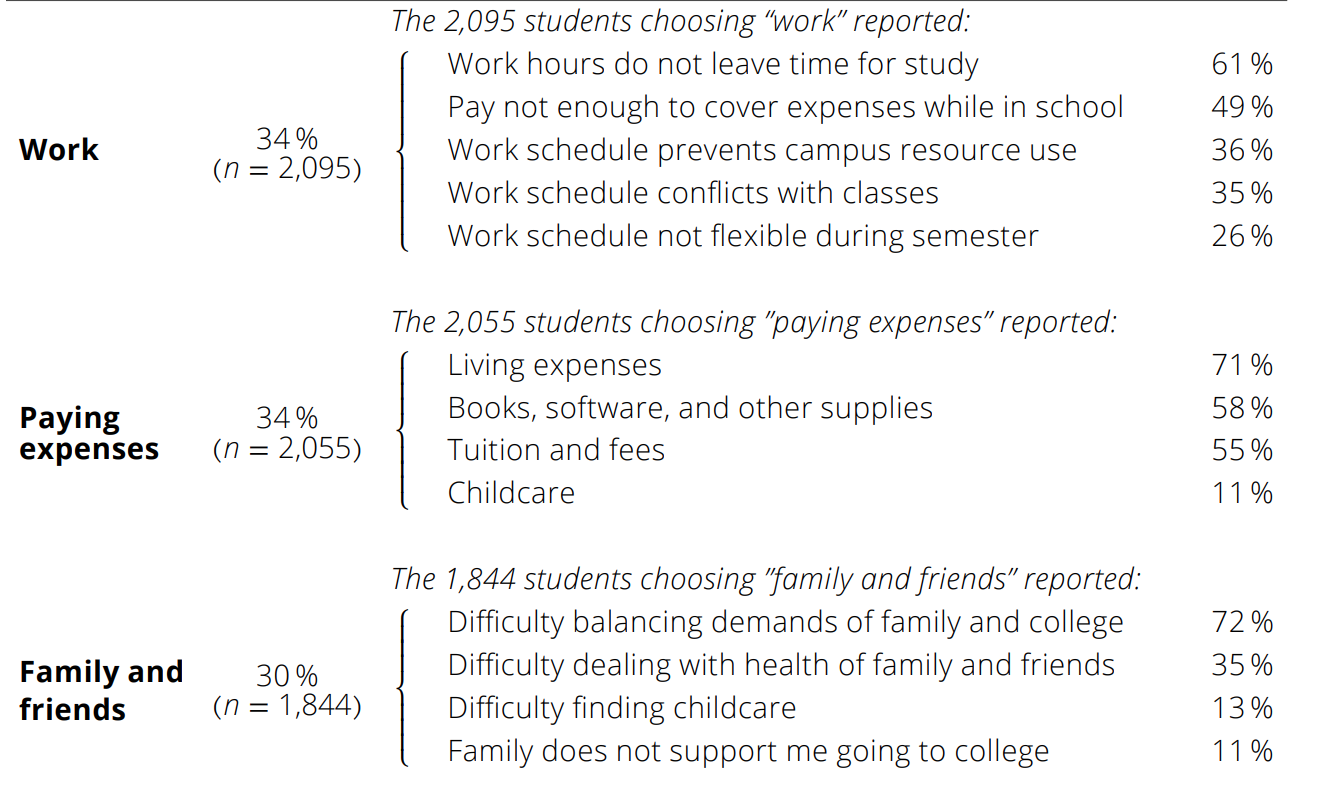

About 2,100 students said work was the largest challenge they faced, with 61 percent saying the number of hours they worked didn’t leave them enough time to study. About 50 percent of students reported their wages didn’t cover their expenses. Students also reported difficulty paying for living expenses, textbooks, tuition and childcare. Thirty percent of students reported difficulty balancing familial responsibilities with college, dealing with family members' and friends' health problems, and finding childcare. Among those who cited these personal problems, 11 percent said their family did not support them going to college.

“We’ve moved beyond the notion of satisfaction and engagement, which most student surveys tap into,” said Paul Umbach, a higher education professor at NC State and a co-author of the report. “We wanted to help campuses identify areas where they can move the needle on student success.”

Umbach and Steve Porter, also a professor of higher education at the university, said they noticed a dearth of surveys that asked students about the barriers they face to completing college and wanted to provide a tool that colleges could use to eliminate those barriers and boost graduation rates. The national survey is based on smaller surveys the community colleges used to glean information specific to students on their individual campuses. Each college receives the same survey but has the option to add 10 of its own questions for an additional fee. Umbach and Porter are hopeful more colleges will be interested in purchasing individualized surveys.

"We saw a gap among the surveys out there," Umbach said. "None are asking students directly about the challenges they face and the different strengths their colleges have related to student success."

The most well-known student survey is produced annually by the Center for Community College Student Engagement at the University of Texas at Austin. CCCSE's survey addresses student engagement, which can be an indication of whether students are learning.

But the CCCSE survey is much more than a student engagement tool; it has detailed information about the many barriers to college completion that students face. Those barriers include financial problems, being required to take costly and time-consuming non-credit-bearing remedial education courses, or only being able to attend part-time. These obstacles can discourage students from finishing college and prompt them to drop out, CCCSE executive director Evelyn Waiwaiole said.

The RISC survey isn't the first to ask such detailed questions of students. The Hope Center for College, Community and Justice at Temple University has been encouraging students to identify their housing, food, transportation and financial insecurities, she said.

"I welcome any survey that is providing data to help colleges get better," Waiwaiole said. "We are about institutional improvement."

Kay McClenney, a senior adviser to the American Association of Community Colleges and former director of CCCSE, said the RISC survey identifies issues on a national scale that colleges have attempted to find on their own locally.

She said the work and financial challenges cited by students could be useful for colleges considering initiatives -- such as a plan to encourage more part-time students to attend full-time -- to help students succeed. A growing number of states have been experimenting with different types of financial incentives to encourage students to take more credits, which increases their likelihood of graduating.

“The practice of sharing with every student a full-time financial aid package and allowing them to make a more informed decision between whether to attend full-time or work at McDonald’s may make a difference,” she said.

Of the students surveyed, about 60 percent attend college full-time and 40 percent part-time. Nationally about 64 percent of community college students attend part-time.

Colleges and states should view the results as evidence that financial aid and social service policies are not doing enough to help community college students succeed, said Katharine Broton, an assistant professor at the University of Iowa and a faculty affiliate with the Hope Center for College, Community and Justice at Temple.

“It’s clear that paying for college, juggling work and family responsibilities are academic issues critical to student success,” she said.

There are teaching and learning areas that could be improved, too, but equally important is ensuring students’ basic needs are met, Broton said

Porter and Umbach expected students to cite work responsibilities and finances as major barriers, but they were surprised by other challenges students identified.

“The biggest surprise we had was parking,” Porter said. “This is a big issue for them because of personal schedules or work schedules.”

He said many students don't have the luxury of being able to arrive on campus an hour early to look for available parking spaces, only to end up late for class or for exams.

Nearly 1,300 students identified parking as a challenge, with 86 percent reporting they have a difficult time finding parking near or on their college campuses. Only 10 percent said parking near their campus is too expensive.

Another surprise was the 1,300 students who identified online classes as a challenge. Fifty-three percent of them reported difficulties with learning online, and 44 percent said the lack of interaction with faculty is a problem. Nearly 40 percent of students said they had problems keeping up because their online courses didn’t have regular class times.

“Throwing courses online with no real interaction is a recipe for disaster,” Phil Hill, an education technology consultant and co-founder of Mindwires Consulting, said in an email. “Not providing online community college students with proactive advising and support services is also a big problem.”

Hill said the California Community College System's Online Education Initiative, which he worked on as a consultant, is a good example of a well-designed online learning system. It helped close the gap between the rate of students successfully completing traditional courses and online classes from 17 percent in 2006 to 4 percent in 2016.

“Online education can work for community college students and is an important part of student access, but there are no silver bullets,” Hill said.

Despite the challenges cited by the students surveyed, they had positive opinions about their colleges that indicated that two-year institutions are doing well over all. Ninety-five percent of students reported they would recommend their college to a friend. About 50 percent of students said their college is worth more than what they're paying, and 48 percent reported their institution had a fair value.

“They do see a better life for themselves, and they have an overriding optimism about the potential of college,” said Lauren Walizer, a senior policy analyst with the Center for Law and Social Policy, adding that the survey confirmed much of the work CLASP has done in identifying challenges two-year college students face. She noted, however, that optimism is not always enough to carry students to the finish line.

State funding of community colleges is another contributing factor to students' academic outcomes. State governments often underfund community colleges, which limits the resources and support services they can offer students, Umbach said.

A report released last year by the Century Foundation found that states spend less on community colleges, which enroll high numbers of disadvantaged students, than on public four-year institutions. Educational spending per public four-year college student increased by 16 percent between 2003 and 2013, while per-student community college funding increased by just 4 percent, according to the report.

“Community colleges are already underfunded, and they are limited in many ways and don’t have the resources to do more,” Walizer said. “Inadequate funding at public institutions is generally a big problem. But with more funding, they could offer more classes at more times and have the resources to pay professors.”