You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

This spring at Western Michigan University, nearly 23,000 students -- including almost 18,000 undergraduates -- are taking part in something called WMU Signature Designated Experiences. In addition to attending class, students agree to participate in as many as 12 out-of-class “designated experiences” in one of nine pathways. They include civic engagement, health and wellness, leadership, social justice, and sustainability, among others.

Students join clubs, attend lectures and perform community service. A recent listing invited them to hear Mary Robinson, Ireland’s first female president, speak on climate issues. Another invited students to spend a few hours each Friday this semester at the WMU Open Bike Shop, repairing their own bicycles. Still another invited them to study the New Testament book of Romans. Students are required to reflect on the experiences in writing, and in the end all of it will somehow make its way into students’ academic transcripts.

Though efforts to capture the effects of such learning are not new, the past four years have seen a resurgence of interest in the idea -- as well as an acknowledgment that institutions must capture students' “learning outcomes” in both formal and informal settings.

The traditional transcript mostly serves as a helpful chronology that tells universities whether a student is ready to take on more in-depth academic study, said Thomas Black, registrar and assistant vice provost at Johns Hopkins University. Faculty know how to interpret them, but “to any other third party, it is just opaque,” he said.

Most transcripts, Black and others said, tell employers little about a student’s knowledge and skills. And students often don’t have any more ability than anyone else to figure out what their own transcript means.

“It’s the record of everything you’ve forgotten,” Black said. “It’s a big collection of experiences, and they just all kind of flow together -- you can’t decipher them.”

Black, who began experimenting early on with different kinds of student records at Stanford University, called the typical transcript “a mess” when it comes to figuring out the shape of a student’s academic career. It prominently features letter grades, of course, but creeping grade inflation means it’s not actually a good indicator of whether a student has mastered a subject. “You really can’t trust or know what those grades mean.”

Black, who has spent 40 years in academe, admitted that he was once the “biggest defender of the transcript as the be-all, end-all.” Now, like many who have been critically investigating it, he’s not so sure of its usefulness. “I’ve realized that that document is really not very good at making clear what a student has been provided and what a student has accomplished.”

Increasingly critics like Black also worry that transcripts do a poor job describing what a student has done outside the classroom, where many of their most important learning experiences can take place. Study abroad experiences, community service and the like are happening all the time, Black said, “and we don’t document them.” The typical transcript, for instance, may devote just two words -- “independent study” -- to an experience “that could have been transformative for that student.”

Others aren't so sure that these "transformative" experiences should be highlighted so heavily, or that students should spend much time on them at all during their precious undergraduate years. Higher education, they say, should focus on intellectual, not practical, pursuits.

“Americans and America have always been suspicious of purely intellectual activity,” said John Kijinsky, a former administrator and current English teacher at the State University of New York at Fredonia. Kijinsky, who has written on the topic for Inside Higher Ed, said his own department is focused heavily on "experiential learning," which baffles him. “It’s very odd that people, particularly in the humanities, just jump on that bandwagon right now.”

While a short spell working or performing community service may be valuable, he said, students have the rest of their lives to take part in these experiences. “If you have a choice between working at the local historical society, that’s nice -- but it means you’re not going to read Hegel? You can work at the historical society any time.”

He added, “Most people, in their lives, are going to have only four years of challenge, of really being intellectually challenged. Some of us are going to be wonky and become professors or editors for higher education journals, so we’re always dealing with ideas. But [for] most people, it’s pretty short.”

Proponents of experiential learning have the best of intentions, he said -- and are rightly focused on giving all students, including disadvantaged students, a practical education. But this approach can shortchange students, substituting practical work, travel and volunteering for a more important experience: the hard work of learning complex, difficult material that trains them to concentrate, think and read texts closely. “There’s no way that an internship experience is going to give you those sorts of things,” Kijinsky said.

Making Learning More Efficient

Next fall, Drury University will begin requiring students to earn at least two professional or “life” certificates in addition to their typical required course work. The life certificates build on students’ intellectual passions and interests, said Provost Beth Harville. She said students are often careful about which courses they take, fitting them together cleverly. “But when they’re just transcripted as a long list of courses taken over a long period of time, it’s difficult for an employer or a graduate school or, let’s be honest, even a student, to see how these things fit together.”

The professional and life certificates include Comparative Mythology, Christian Ethics, the Politics of Food, Neurodiversity in Life, Society and the Sociology of Sport, and the Social Science of Wrongful Convictions, among others. The results will show up in a digital portfolio on their transcript.

“What we really wanted to create was something that provided students really important learning experiences,” Harville said. “It’s about learning some content, it’s about learning some skills, it’s about learning to apply it. But when you do it just in a class here, a class here, a class here, it’s really disjointed.”

Darin Hobbs, registrar and director of academic records at Western Governors University, said that by this June he expects to roll out the prototype of a skills-based transcript, to be used by all programs by 2020.

WGU is experimenting with alternative transcripts -- the competency-based university already breaks out “other earned credentials and certifications” on its transcripts. Hobbs said the traditional transcript will endure because it remains a “tool of communication between institutions.” But WGU and others need to produce a transcript that is “consumer facing,” one that helps students succeed in the workplace.

That’s especially true of WGU, where the average student is in his or her mid-30s and has already had work and, often, military experience.

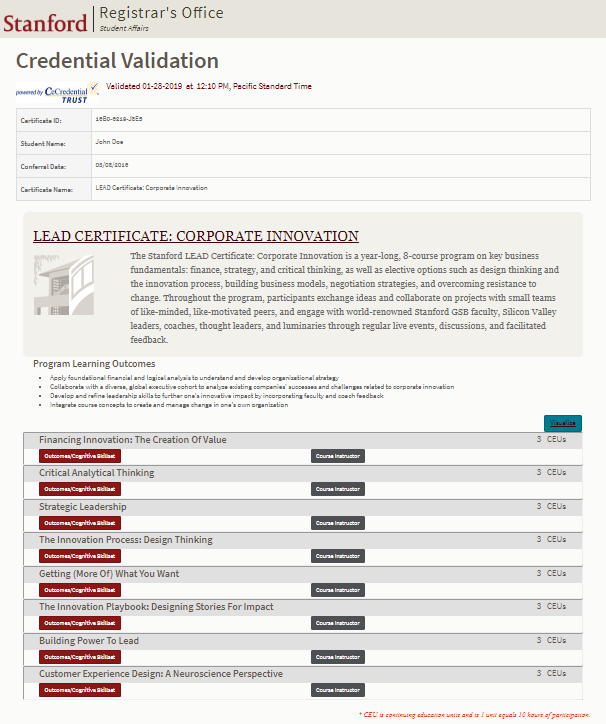

He sees transcripts as less an institutional record than a kind of portable tool that follows students throughout their lives, giving them access to credentials whenever they need it. “The notion that I have, and I believe my university has, is that the student owns the record,” he said. “We own the validation of the record.”

Annemieke Rice of Campus Labs, the Buffalo, N.Y.-based technology company that helped Western Michigan build its Signature Designed Experiences program, said she sees it as a way of making students’ out-of-classroom learning more efficient, allowing them to, in effect, “drive through a pathway rather than bump into learning.”

For instance, if a student focuses on civic engagement, she’s encouraged to volunteer, mentor students at a local high school and take an alternative spring break to help a hurricane-affected community get back on its feet. The system records each action a student takes and how it fits in with the whole -- in effect, it’s a learning management system for learning taking place outside of class.

Rice said colleges and universities are under increased pressure to tell employers what students are learning -- with “increased focus on the student doing something besides showing up.”

At Stanford, Black helped develop a way to better document community service, in the process creating a structure that audited the quality of the program. Stanford also began requiring students to write about the experience, which the students found “very powerful,” he said. Black also found a way to tweak student transcripts to include the name of faculty members under whom students studied -- and to include a hyperlink to student research.

Changes like this represent a huge opportunity, not just for students but for prospective employers and graduate schools, said Rodney Parks, Elon University’s registrar. Most systems, he said, limit descriptions of student work to just 30 characters. So a student might spend months on “an extremely interesting” research project. “Right now, your academic transcript would just say, ‘Research.’”

Elon, which pioneered experiential transcripts more than 20 years ago, now routinely links to students’ research papers, grant award letters and websites of organizations where students have had a “significant service experience.”

Experiential learning, Parks said, is “built into the fabric of the curriculum itself” at Elon. To graduate, students must complete two experiential learning requirements out of a possible five. “But if they only have two, it’s not going to be a very good-looking transcript,” he said. Likewise, if a student decides that certain low-level kinds of community service are likely to make him look attractive -- if he gives blood during a blood drive, for instance -- that will only be meaningful if it fits into a bigger commitment to community service.

“If that’s the only thing that’s on your experiential transcript, that transcript is not going to help you very much,” Parks said.

Most Elon students end up with transcripts featuring about nine “substantial” experiences, he said. “If it’s not a substantive transcript, then it’s not going to be something they want to send to potential employers.”

While Elon helped put these ideas on the map, efforts over the past four years to transform the college transcript have had a big effect. Funding from the Lumina Foundation to the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers and to Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education have pushed about a dozen institutions try new ideas.

Parks next wants to figure out a way to help students choose courses more efficiently, adding tags to course descriptions that help students find course work in key areas not typically broken out -- for instance, if a student wants to take as many courses as possible that feature design thinking, she should be able to see all of the courses that apply.

Reached by email, Parks agreed to talk even though he's busy teaching in South Africa, where he and a colleague are leading a short January-term course on apartheid with 29 students. The course features not just visits to key sites in Cape Town, Johannesburg and Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned. It also features community service: while in South Africa, students are volunteering in an elder-care facility and doing prison outreach.

“We’ve done a lot of service while we’re down here,” Parks said. “‘The Elon Way’ isn’t just to go visit a site and look at a distance. The Elon Way is to go to a site and do your best to embed yourself into a culture, understand the culture and give back to the culture. If we can do that, we feel like we really give the students a more substantive experience.”