You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

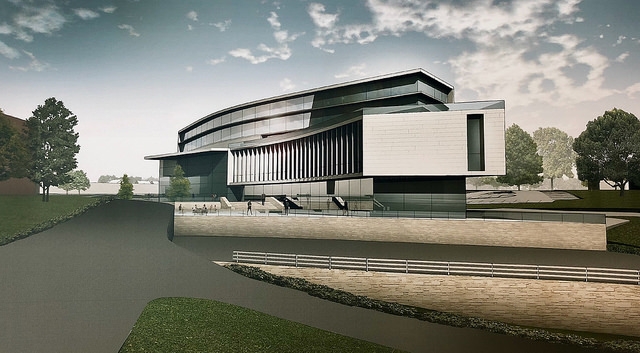

Artist's rendering of Marist Health Quest School of Medicine

Marist College

As its fellow midsize, modestly endowed private colleges look nervously to the future, Marist College in New York’s Hudson Valley is making a bold, nearly $180 million bet: last month, it announced that it will partner with a regional health-care provider to build a new medical school.

Marist Health Quest School of Medicine is expected to open its doors in 2022, reaching capacity in 2032 with about 500 students.

Adding a medical school to a private college is “honestly a big leap up in scope and complexity,” said President David Yellen. But it makes sense, he said. “If you have the resources, there’s room for another good medical school. And we think it will boost our status and reputation.”

The move is unusual -- if not unprecedented -- for a regional institution. In 2013, Marian University in Indianapolis did much the same, opening its College of Osteopathic Medicine, only the second medical school in Indiana.

In both cases, relatively nonwealthy -- if economically secure -- private institutions surveyed the educational landscape and decided that training doctors made sense. Opening a medical school represents not just a worthy pursuit, they concluded, but a possible key to long-term financial security, despite a byzantine and ever-shifting health-care industry.

Marian president Daniel Elsener said the endeavor turned out to be so enormous that it’s best understood not as a typical campus expansion but as an “intergenerational” undertaking.

But he said it is a smart investment, since most medical students eventually become physicians -- who become donors.

“The likelihood that they can support their institution as an alum increases,” he said.

Geoffrey Young, senior director for student affairs and programs at the Association of American Medical Colleges, said the demand for new doctors will continue to grow. “We have a generation of physicians -- the baby boomers -- who are at or are rapidly approaching retirement age,” he said.

And as the median age of Americans inches up, “We know that we’re going to continue to need physicians to care for our population,” said Young, a former admissions dean at the Medical College of Georgia. He said the field has seen steady growth in the total number of applicants. “Over all, medical school remains a very attractive option for those who are qualified,” he said.

According to recent AAMC data, the U.S. faces a severe physician shortage over the next 12 years. Its 2017 analysis found that the number of new primary care physicians and other medical specialists is not keeping pace with the demands of a “growing and aging population.” By 2030, it predicted, the U.S. will need between 40,800 and 104,900 more physicians than it is expected to produce.

The analysis found that primary care shortages won’t be as bad -- at most, AAMC found, we will come up short by as many as 43,100 primary care physicians. But surgical specialties and others are expected to see a shortfall of as many as 61,800 practitioners by 2030. Other specialties, such as emergency medicine, anesthesiology, radiology, neurology and psychiatry could see shortages that are about half as large.

AAMC statistics suggest that the nation’s 152 accredited medical schools were slightly more competitive last year than they were nine years earlier: in 2017, the schools accepted 41.2 percent of applicants. In 2008, they accepted 42.7 percent.

Over all, the acceptance rate dropped even as the total number of med school slots grew, from 18,036 in 2008 to 21,338 in 2017, or by 18.3 percent.

Mostly that’s because in the same period, the number of applicants grew at an even faster rate: 22.3 percent. In 2017, nearly 9,500 more students applied to medical school than in 2008, but institutions could accommodate only 3,302 more applicants, according to AAMC statistics.

Though the costs to underwrite a brand-new medical school are considerable, analysts have actually said Marist’s move is not as risky as it seems. For one thing, Health Quest has committed to funding construction of the facility that will house it.

Moody's Investor Services last month said Marist’s plan would have no immediate impact on its $104 million in outstanding rated debt, or on $40 million in proposed bonds to be issued through the Dutchess County, N.Y., Development Corporation. The costs associated with launching and supporting the medical school are “manageable,” Moody’s said, noting that they’ll be split evenly between Marist and Health Quest, which already runs four hospitals in the Hudson Valley and northwestern Connecticut.

Marist will spend about $25 million over the next five years, a small portion of its “sizeable” $290 million in spendable cash and investments, Moody’s said.

Yellen, the Marist president, said building the new school “is only possible because we’re doing very well financially, in an environment that’s pretty challenging for private colleges.”

He estimated that the college and Health Quest will spend nearly $180 million to get the new school to capacity in 2032. It will likely never turn a profit, Yellen said, but if all goes as planned, it will help raise Marist's reputation and drive enrollment to other programs such as the sciences. “This isn’t something we’re doing to generate revenue for the college at all, in any direction -- just the opposite,” he said. “We think it’s going to cost us money for a long, long time.”

Yellen also said the school isn't designed “to spin off money to be used for other purposes.” While he anticipates that alumni could someday give back generously, it'll likely be to the medical school and not to Marist's general fund. “We’re not expecting that medical school alumni will give money to help Marist College build a new undergraduate dorm,” he said. “But it’s kind of a rising tide raising all boats.”

He said the move makes sense for the region: the nearest medical schools in the region sit either in Westchester and Rockland Counties, 50 miles south, or in Albany to the north, 80 miles away.

“In between, there’s a million people,” he said.

Though the success of the new school won’t necessarily be judged by the percentage of graduates who stay to practice medicine in Dutchess County, he believes the area’s natural beauty, low cost of living and proximity to New York City will make it an attractive place for future physicians to put down roots. The new school, he said, will be located just a half mile from Poughkeepsie's Metro North commuter train station -- the trip to Grand Central Station takes about an hour and a half. “This is a beautiful, dynamic part of the country that has a mix of natural beauty and a proximity to New York,” he said.

The recent AAMC data on medical school matriculation show that there’s “a dramatic oversupply of really qualified” medical school applicants, Yellen said. “We’re not worried about enrolling a full class of really good people.”

Part of the new school’s appeal will be its focus on medicine assisted by artificial intelligence and cognitive computing, which will be built into the curriculum. “We want our medical students to begin to be educated in that, and to begin to be acclimated to that.” As data-driven decision making becomes a bigger part of medical practice, “they’ll be ready,” he said.

Despite its isolated location, he predicted that Marist “will do just fine in that competition for the best students, over time.”

Robert Friedberg, Health Quest's president and CEO, said bringing a medical school to Dutchess County would familiarize students with the region. "We’re hoping that many of them will find it a desirable area" and apply for residencies, he said.

Robert Friedberg, Health Quest's president and CEO, said bringing a medical school to Dutchess County would familiarize students with the region. "We’re hoping that many of them will find it a desirable area" and apply for residencies, he said.

He said he and Yellen “just shared the vision about how this would look and how it will work.”

Marist's modest size, he said, wasn't a consideration. “They have strong premedical programs and they have some postgraduate programs as well in the medical arts -- they were just positioned really well.”

Alumni Shift Could Pay Off

Marian’s Elsener said Indianapolis is “a great environment to attract talent.” The university boasts that it offers a “faith-based, liberal arts environment,” and has committed an estimated $80 million to $90 million to the new school over the past decade. “If you don’t bring a lot of resources to the game, you should stay off the field,” he said, noting that start-up costs are “very, very significant. If you aren’t prepared to take care of that, it can pull down the whole institution rather than raising it up.”

He said the move could pay off as institutions like Marian shift away from graduating mostly teachers, nurses and social workers -- through the 1980s and 1990s, about 80 percent of Marian alumni ended up in these professions -- and add more disciplines like medicine and engineering. The shift, he said, could help the university's bottom line, since these new alumni are more likely to be able to give back generously in future decades. Teachers, nurses and social workers, he said, are “wonderful people,” but they don’t always earn sizable wages.

Patrick McCabe, a Moody’s analyst, said a new medical school “carries both long-term potential benefits as well as more immediate potential risks. Once successfully up and running, a medical school can enhance a college’s reputation and profile, driving additional revenue growth and often resulting in enhanced fund-raising.”

But during the start-up phase, he said, “there can be both operational and financial risks including accreditation, capital needs and unexpected uses of liquidity.”

The Marian project experienced a huge and unpleasant surprise in 2016, when donor Michael Evans, the medical school’s namesake and a key early supporter, backed out after donating just $10 million of a planned $48 million gift. Evans, CEO of AIT Laboratories, a local toxicology testing firm, had fallen on hard times amid a decline in Medicare reimbursement rates and a lawsuit filed by the U.S. Department of Labor, which said he'd sold the company to employees in 2009 for more than it was worth. Evans settled the lawsuit for $3 million, but Marian had to look elsewhere for funding.

In the two years since, Marian has raised more than the $38 million Evans promised, a spokesman said. The larger facility remains the Michael A. Evans Center for Health Sciences.

Many health-care experts praise osteopathic medicine for meeting patients' needs and for emphasizing primary care more closely than many traditional M.D.s. But it has also come under criticism in a few cases. Elsener said critics are “uninformed” about its methods, its standards and its efficacy. “There’s no doubt that an osteopathic doctor is high-quality,” he said. The field also “sits well in a Catholic university,” which emphasizes focusing on the “whole person.”

Elsener said having potential physicians, surgeons and anesthesiologists as students can’t be overstated: medical students are more willing than other graduate students to take on debt to finance their education. “A medical student can calculate their lifetime earnings,” Elsener said. Carrying debt, for these students, is almost always a smart investment.

Charging more of the student population for full tuition also helps Marian with its discount rate, he said. “Most institutions today are in discount misery.”

Over all, he said, attracting as many of these students as possible is smart for an institution. “Unless you’re heavily endowed, you’d better pay attention to all aspects of the financial model.”