You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

'American Political Science Review'

A major political science study from last year explored publication patterns across 10 prominent journals, finding a significant gap in publication rates for men and women. The gap couldn’t be explained away by a low overall share of women in the field, the article said, prompting soul-searching among editors about whether they were biased against female authors.

A new PS: Political Science & Politics report involving self-audits at five major journals suggests that editorial practices are not, in fact, biased against women. While positive, the findings are also disconcerting, since it remains unclear as to why women are underrepresented as authors in esteemed journals in the discipline.

“Even though the journals differ in terms of substantive focus, management/ownership, as well editorial structure and process, none found evidence of systematic gender bias in editorial decisions,” symposium co-chairs Nadia Brown, associate professor of political science and African-American studies at Purdue University, and David Samuels, Distinguished McKnight University Professor of Political Science at the University of Minnesota, wrote in their introduction to the PS report.

“These findings raise additional questions about where gender bias may occur and why,” they said. “We urge a continued conversation and examination of why women remain underrepresented as authors in political science journals, particularly top-ranked journals.”

If not gender bias, Brown and Samuels wrote, other factors may be at play. For example, they said, the American Political Science Association in 2017 surveyed members as to where and why they prefer to submit manuscripts. The suspicion is that women may be self-selecting out of submitting to the kinds of journals that grease tenure and promotion wheels and otherwise benefit their careers.

“It is very, very difficult to earn tenure at, let’s say, the top 50 departments without publishing in one of the top journals” studied in the 2017 report on gender and publication rates, said Maya Sen, an associate professor of political science at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government who has studied gender in the discipline. “It really screams at you, we need to understand why and where this is happening.”

Possible alternative explanations, she said, include “pipeline” issues regarding potential future political scientists who are women, possible underconfidence among women and overconfidence among men seeking to publish, and the subtopics most studied by women.

A Place to Start

The PS symposium was inspired by an article published last year in the journal, called "Gender in the Journals: Publication Patterns in Political Science." For their study, Dawn Langan Teele, Janice and Julian Bers Assistant Professor in the Social Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania, and Kathleen Thelen, Ford Professor of Political Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and president of the political science association, counted all authors, by gender, who published in 10 of the field’s best known journals over 15 years. While women made up 31 percent of members of the APSA, they wrote, women made up just 18 percent of authors in the American Journal of Political Science over the period studied and 23 percent in the American Political Science Review, which is widely considered the field's premier research journal. Publication rates for other journals were similarly slanted toward men, save two. Political Theory and Perspectives on Politics saw women writing about one-third of articles.

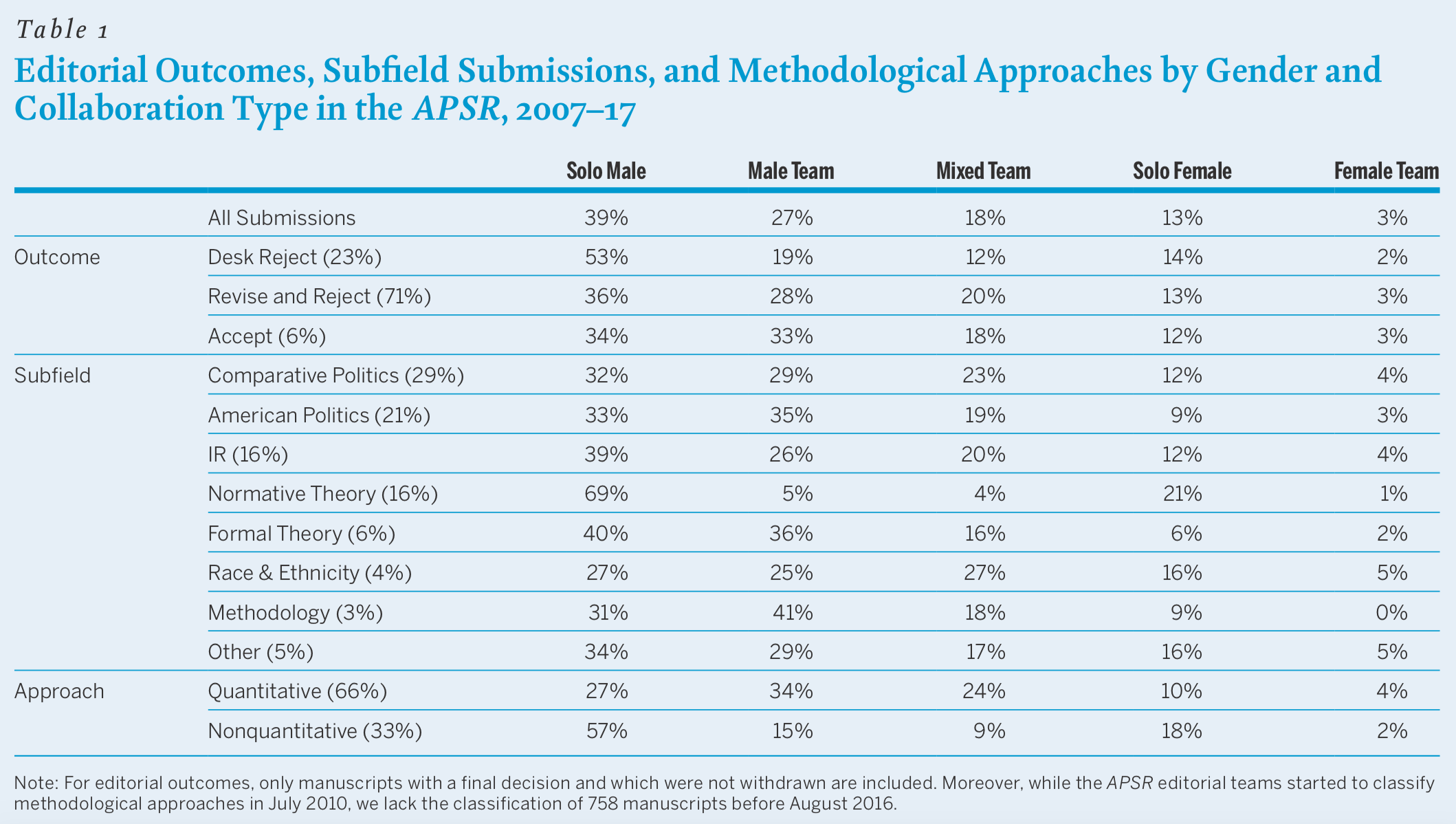

Beyond a general gender gap, Teele and Thelen also found that women remain underrepresented in terms of co-authorship. While single male authors still represented the biggest share of all bylines (about 41 percent), the second most common byline type was all-male teams (24 percent). Mixed-gender teams were about 15 percent of the sample. All-female teams and single female authors were 2 percent and 17 percent of the sample, respectively.

A possible explanation is political science’s qualitative-quantitative divide, they said, in that female authors wrote more of the published qualitative articles in the study. Flagship journals, meanwhile, tend to publish more quantitative studies.

“Here’s the general pattern we observed: The journals that publish a larger share of qualitative work also publish a larger share of female authors,” Teele and Thelen wrote in a related op-ed for The Washington Post. “Conversely, the more a journal focuses on statistical work, the lower its share of female authors.”

Examining Journals' Biases

Teele and Thelen’s study didn’t accuse journals of outright gender bias in selecting articles for publication. But it did give some editors pause as to whether they were contributing to the publication gap. While most journals use some level of blind review, social science research is often shared at conferences, in working papers and on social media before it’s submitted for publication -- meaning sometimes editors and reviewers know who wrote an article that is stripped of identifying information. Sen, of Harvard, also said that work on gender and politics is very likely to be by a female author.

Samuels, at Minnesota, editor of Comparative Political Studies, was among those concerned editors. He ran an internal audit to see whether there were any unknown biases within the editorial process and showed a copy to Thelen. She invited him to join a task force to expand the work. Samuels said recently that he invited a group other editors to participate in the symposium, some of whom he knew were already engaged in similar projects. Together with Comparative Political Studies, they represent five journals: American Political Science Review, Political Behavior, World Politics and International Studies Quarterly.

Samuels wrote in his self-study that Comparative Political Studies does “fairly ‘well’ in terms of gender balance, at least compared to other journals in political science,” based on Teele and Thelen’s research. The journal employs a “quasi-triple blind review process,” he said, in which submissions are blind reviewed internally and editors decide to send the paper out for blind peer review or not. Editors learn the author’s name, rank and institutional affiliation after the initial read.

Based on 2,134 papers submitted between 2013 and 2016, gender did not systematically predict a manuscript’s success at any stage of the editorial process. More important factors, meanwhile, included rank, co-authorship and methodological approach. At the internal review stage, for example, solo-authored papers were less likely to be sent out for peer review than co-authored papers, regardless of the authors’ genders. Qualitative papers were less likely to be sent out than quantitative and mixed-method papers. About two-thirds of all submissions were quantitative, compared to one-fourth that were purely qualitative. Qualitative papers faired worst at the internal review stage, Samuels wrote, with just 25 percent of these sent out for review. Just about 20 percent of those (26 out of 128) were eventually accepted.

As for gender, Samuels wrote, “women simply submit relatively fewer papers, whether on their own or in collaboration with other scholars, male or female.”

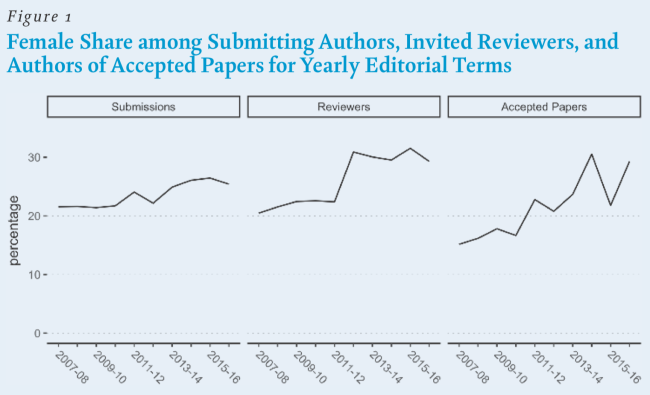

American Political Science Review’s editors, Thomas König and Guido Ropers, both political scientists at the University of Mannheim in Germany, wrote in their self-study that the general-interest journal rejects 95 percent of all submissions via a double-blind review process. They noted that the journal introduced a bilateral decision-making process between lead editor and responsible association editors in 2016, in part to reduce potential editor bias in particular subfields. Looking at 10 years’ worth of publication data, or more than 8,000 submissions and 18,000 reviews, König and Ropers found no evidence of gender bias in the editorial process -- solo male authors dominated submissions and actually had the highest desk rejection rate.

Addressing the qualitative-quantitative divide, the editors noted that the share of female authors among quantitative submissions was 26 percent in 2016-17, compared to 24 percent among nonquantitative submissions over the same period. So there is "no indication that the higher desk rejection rate for nonquantitative submissions penalizes female authors, as hypothesized by Teele and Thelen."

Over all, König and Ropers wrote, “our analysis points much more to the problem of a systematically low submission rate of female authors as explanation for the underrepresentation of women” in published articles.

The results for the remaining journals were the same: no evidence of gender bias in the review process could be found.

David A. M. Peterson, a professor of political science at Iowa State University and editor of Political Behavior, wrote in his report that “the skew of publications” seems to be due to the male-dominated submission pool. “This is still disappointing,” he wrote. “When I became editor, one of my goals was to solicit more manuscripts from women. It appears I have not been successful at these efforts.”

Peterson said last week that the journal, which historically focuses on U.S. presidential elections, was in “great shape” when he took over as editor several years ago. Yet he wanted to “diversify who was submitting. The review process takes care of itself at some point, so I wanted to make the journal more welcoming for a diverse set of research questions” and researchers.

And Political Behavior has improved on that front, he said. Yet across all the journals studied, it appears there’s more work to do. (He noted that while the journals included in the symposium represent a range of processes, he wished it had included one with single-blind review, to round out the sample.)

Some Answers, More Questions

Brown, symposium co-author, said she’s tried to do the same as co-editor of Politics, Groups and Identities (which was not involved in the study). That means defying journals’ traditional gatekeeper status, including by working with potential authors to help them frame their arguments in ways that give them the best chance at publication.

The lack of systematic gender bias in the editorial process doesn’t mean academic publishing is free of gender bias, Brown cautioned. She’s involved in the APSA’s current study examining possible bias in the submission process, for example.

“There’s a big gender gap within these publications and the data we have raise more questions than answers,” Brown said.

Teele, the co-author of the 2017 study that inspired the symposium, said she’s currently working on a manuscript with Samuels that suggests underrepresentation of women authors in university press books, not just journal articles.

She said one “call to arms” on the data available thus far is that women need to be welcomed onto collaborative teams early in their careers.

“Bring women into labs and put them on papers,” she said.

Teele said the data also point to bigger, largely ignored questions about academic work, such as what meaningful productivity and scholarly output looks like.

“Our discipline needs to have conversations about productivity and how much anybody can write or read about these things,” she said.

Interestingly, APSR's editors address the question of quality over quantity, saying, "If we assume that editors are able to objectively judge the quality of manuscripts at the desk rejection stage of the editorial process without discriminating against gender, it speaks in favor of a lower average quality of solo male submissions. It would hint to concerns that male and female authors have different quality standards when submitting their work in the first place."