You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

A new study in PS: Political Science combines elements of prior research on gender bias in student evaluations of teaching, or SETs, and arrives at a serious conclusion: institutions using these evaluations in tenure, compensation and other personnel decisions may be engaging in gender discrimination.

“Our analysis of comments in both formal student evaluations and informal online ratings indicates that students do evaluate their professors differently based on whether they are women or men,” the study says. “Students tend to comment on a woman’s appearance and personality far more often than a man’s. Women are referred to as ‘teacher’ [as opposed to professor] more often than men, which indicates that students generally may have less professional respect for their female professors.”

Based on empirical evidence of online SETs, it continues, “bias does not seem to be based solely (or even primarily) on teaching style or even grading patterns. Students appear to evaluate women poorly simply because they are women.”

Lead author Kristina Mitchell, director of undergraduate education and online and regional site education for political science at Texas Tech University, said Tuesday that her study and others like it demonstrate that “we must find an alternate measure of teaching effectiveness -- especially if we plan to use these measures in hiring, tenure and promotion decisions.”

Real-time feedback, along with highly targeted questions about teaching practices, are superior methods to asking general questions such as “Was your instructor effective? Rank one to five,” Mitchell said. Self-evaluation and teaching portfolios are also a “great way to demonstrate teaching effectiveness,” she added.

Mitchell wrote her paper with Jonathan Martin, now an assistant professor of political science at Midland College. Seeking to build on a 2015 study that found instructors in an online class operating under two different gender identities were rated significantly higher when their students thought they were men, Mitchell and Martin decided to teach identical online introductory political science courses. The idea was to analyze the language students used to evaluate them and their teaching in official university ratings and -- somewhat daringly -- on RateMyProfessors.com.

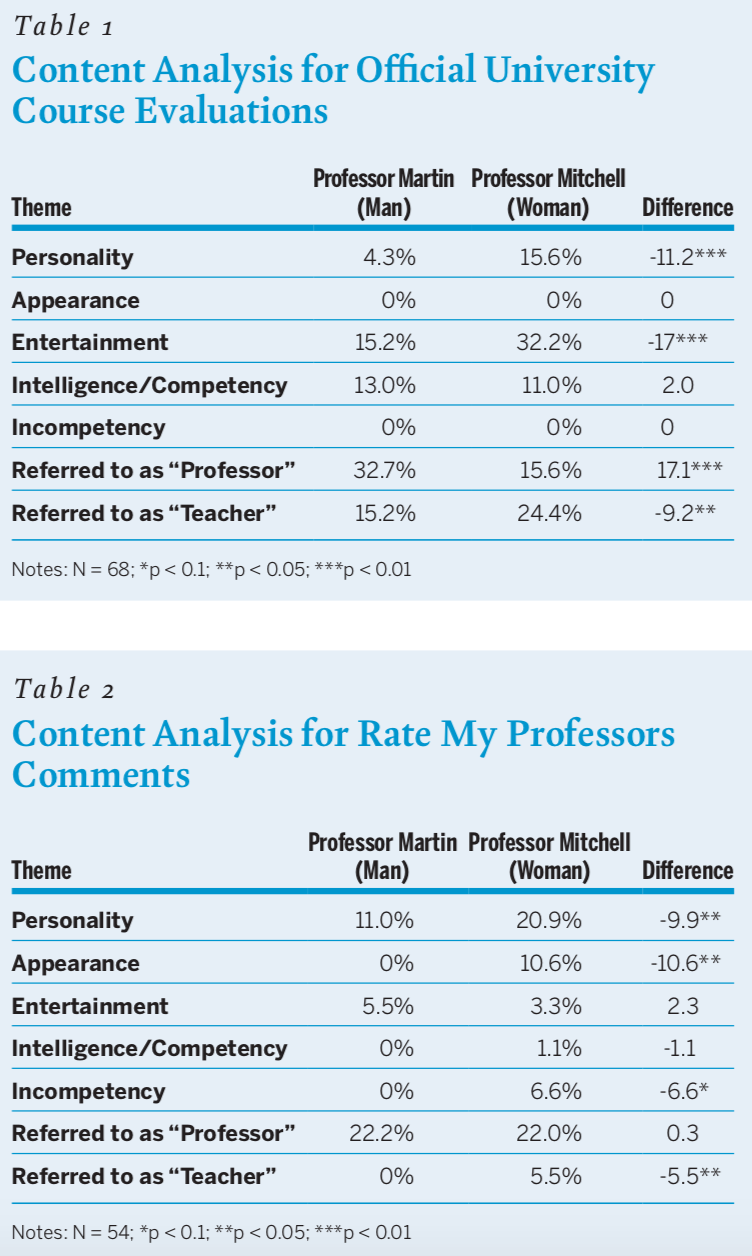

Guessing that students would comment more on their female instructor’s appearance, personality and competency than the male instructor’s, Mitchell and Martin developed the following categories for open-ended student comments: personality, appearance, entertainment, intelligence/competency, incompetency, referring to the instructor as “professor” and referring to the instructor as “teacher.”

Predictably, given prior research, Mitchell and Martin found the language students used to judge them differed significantly -- and not in a gender-neutral way. In university-based evaluations, 16 percent of students commented on Mitchell’s personality, compared to 4 percent who commented on Martin’s. Some 32 percent commented on Mitchell’s entertainment value, as it was qualified in the study, compared to 15 percent for Martin. Mitchell's intelligence was questioned more than Martin's.

Source: Kristina Mitchell

Beyond Texas Tech’s evaluations, Mitchell and Martin also looked at their ratings on Rate My Professors. Mitchell’s appearance was noted by 11 percent of commenters and her perceived incompetence by 7 percent. No one commented on Martin’s appearance or incompetence. Students frequently referred to Mitchell as a “teacher” and Martin as a “professor.”

Over all, the RMP comments were even more gendered, particularly those in reference to appearance.

Notably, the study says, “RMP comments on a woman’s personality tended to be negative (e.g., rude, unapproachable), whereas the official student evaluations tended to be more positive (e.g., nice, funny). In reading the context of each comment, the students mentioning her personality on RMP were almost exclusively taking an online course.”

Mitchell has said the experience was somewhat harrowing, and that she couldn’t believe some of the things students wrote about her, as compared to Martin, when they were administering their courses in identical ways.

The authors rule out that grades played a role in how students assessed their professors, since Martin actually graded his students slightly lower than did Mitchell. So students would not have been retaliating against Mitchell for tough grading via harsher comments.

The disparity in students’ language led to a second line of inquiry: examining how students rated them numerically in official university evaluations. Grouping evaluation questions on what they addressed -- the instructor, the course, technology or administrative issues -- the researchers found that Martin, the man, received higher evaluations, even for questions unrelated to the individual instructor’s ability, demeanor or attitude.

Going forward, Mitchell said, institutions should explore whether telling students about potential biases they bring to evaluations might mitigate the effect. At Texas Tech, she’s working on an infographic telling students what evaluations are used for and asking them to consider such questions as “Would I write this same comment if my instructor were a different gender/race/nationality?”

“I’m hopeful that steps like this can help, but the most important thing right now is awareness,” she said. “We need to be sure that administration and academic leadership is aware of the issue, as they make decisions on what to do about evaluations and hiring.”