You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

A new report on parental involvement and wealth shaping a college student’s experience presents the following striking scenario: one student is accepted into a prestigious dental program, steered by her family, who also carefully shape her undergraduate path.

Another, much poorer student, announces her intention to be a dentist, but without the same level of expertise and service from her parents ends up in $11-an-hour dental assistant job, which doesn’t even require a bachelor’s degree.

Research published recently in Sociology of Education tracks a contingent of female students from 41 families in their years at an unnamed flagship public institution in the Midwest. The authors of the study show how parents' affluence can significantly boost their children’s college and employment prospects. But it also demonstrates that the working class rely on resources -- programs for low-income students, advisers, tutors -- touted by institutions that may not be accessible or affordable.

Because colleges have struggled financially, too, the focus has turned to the more affluent students and their families -- the ones who bring in greater tuition dollars, the researchers said.

“I think to me what was interesting [was] that the institutions often time portray that there are all of these resources available,” said Josipa Roksa, one of the researchers and a professor of sociology and education at the University of Virginia. “It gives these parents a false sense of security thinking that their students are being taken care of, that there are people to guide and mentor them, and that just doesn’t happen.”

The study details the experiences of women on one floor of a so-called party dormitory on the institution’s campus. Generally, because this building is one of the more favored on campus, the wealthier families intentionally placed their students there, while the less affluent students ended up there by chance.

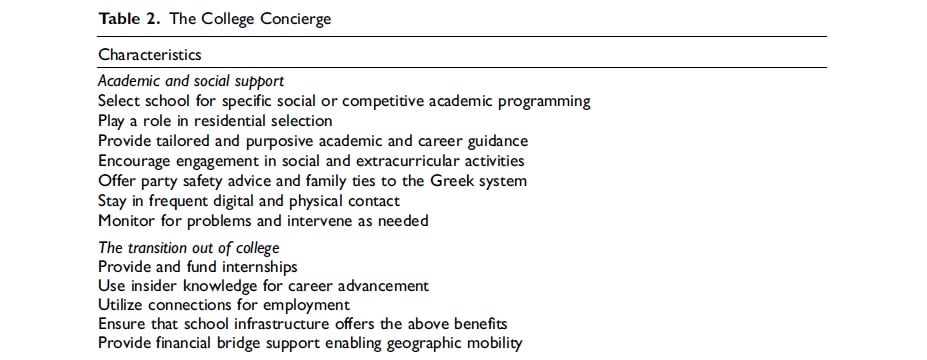

The authors classify the parents into two categories -- one, the richer counterparts, were dubbed the “college concierges” versus the “college outsiders.”

Among those more affluent parents, many stayed in touch with their children regularly, giving them money and advice on academics and their social lives with the intention to lead them to a career.

Among those more affluent parents, many stayed in touch with their children regularly, giving them money and advice on academics and their social lives with the intention to lead them to a career.

Often, this guidance went beyond simply words of encouragement or suggestions. The authors document how many of the richer students in their study had come from out of state but attended the university because it offered a specialized program that the parents had in mind.

The university’s business school is cited as an example. The report references it as particularly difficult to gain admittance to, but says the wealthier students were able to enroll much more easily because their parents could afford SAT and academic tutoring, understood the requirements of the program better, and felt comfortable talking to institution officials.

The nationally ranked business school offered smaller classes and connected the students with career opportunities that the outside majors did not have, the report states.

Their parents also urged their children to join social clubs, including Greek life, and both greased the wheels to ensure they’d be accepted by sororities and counseled them on how to behave at Greek events.

Those parents told them “only to accept drinks from friends” and “don’t funnel drinks,” reflecting an understanding of the party culture of sororities, while low-income parents who might not have attended college themselves reported thinking that Greek culture was much more academically oriented. And one low-income student said of her chances of getting into a sorority, it’s “like a black person working at Abercrombie: not gonna happen.”

In the case of the student who ultimately went to dental school, after college began, her parents sat down with her to review applications for programs and what she needed. They pushed her to join the Crest Club, of which she ultimately became president. The parents of that student paid for summer courses to lighten her load during the traditional academic year so she could focus on other activities.

Laura Hamilton, an associate professor of sociology at the University of California, Merced, and the study’s lead author, noted that the advantages the now dentist had versus the student who worked back in her hometown at a lower wage snowballed. Early on there were few differences between the two women, but ultimately, little separations in their lives were magnified by the time they both graduated college.

“These little tweaks along the way made a huge difference,” Hamilton said.

Kevin Kruger, president of NASPA: Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education, said wealthier parents often understand the opportunities available to their students -- the internships, some unpaid, and studying abroad -- because they attended college and know how those experiences can affect students’ career trajectories.

“Some clear advantages exist,” Kruger said.

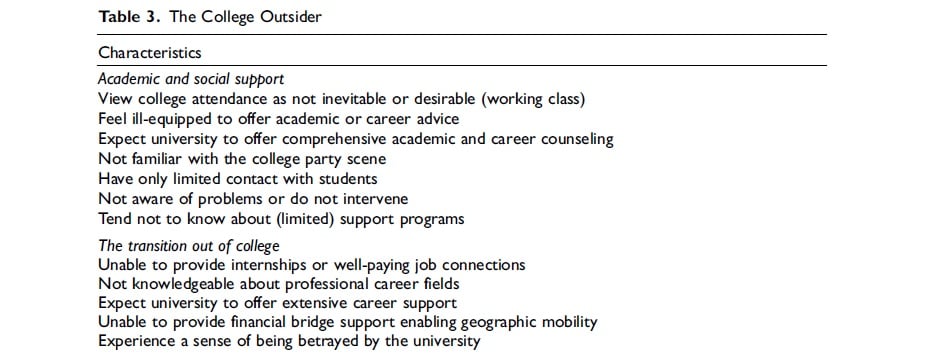

By contrast, the “college outsiders” -- a reference to parents feeling removed from the traditional undergraduate experience -- felt ill equipped to help their children, instead telling them to rely on the advisers and other programs that were supposedly in place.

But these were flawed, the study found. One faculty adviser told her mentee to consider sports communications because the student “liked sports,” but ultimately, she couldn’t land a job because the field required internships. This left her to switch majors, and she was unable to graduate in four years.

The university did have programs in place designed to help poorer students, but the researchers discovered that students were either unaware of them or they helped only a fraction of the population. At the time the study was conducted -- starting around 2004 -- about 20 to 25 percent of the students at the university were either first generation or were from impoverished backgrounds, but only one-third to one-fifth of them were enrolled in any sort of program.

The largest program for low-income students on the campus admitted about 200 students a year but didn’t help at all with tuition.

Ultimately, 75 percent of the wealthier students were able to graduate in four years -- compared to only 40 percent of their low-income counterparts. None of the six students in the “working class,” which the authors defined as coming from a family earning $40,000 or less annually, earned their degrees.

Roksa -- author of one of the most influential books in higher education, Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses, which alleges that students don’t learn much during college -- said institutions are aware that they need to cater more to their low-income students, but they need to do more to help them.

Because over the past several decades local and state funding to colleges has markedly declined, they have turned to recruiting higher-dollar out-of-state students and focused more on pleasing them and their parents, said Roksa.

States have started competing with each other more for nonresident students, including some colleges lowering out-of-state tuition rates, Kruger said. Fund-raising has been more targeted toward parents’ associations, too, which comprise largely upper-middle-class and upper-income families, he said.

What was particularly surprising to Hamilton was the degree to which universities are now cooperating with the wealthier families.

She said that traditionally public institutions, created as a public good, were meant to cater to the constituents of the state, many of whom are now ignored. While some public systems -- such as the University of California system, for instance -- subsidize low-income students’ tuition with dollars paid by the nonresidents, it’s becoming tougher to do so, Hamilton said. UC has of late admitted fewer of these less affluent students in favor of the richer.

“If they can pay, they will have more say,” Roksa said.