You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Betsey Stevenson

Economics remains dominated by men, both in terms of faculty members and students. New research suggests that while economics textbooks aren’t necessarily to blame, they’re not helping close the field’s gender gap.

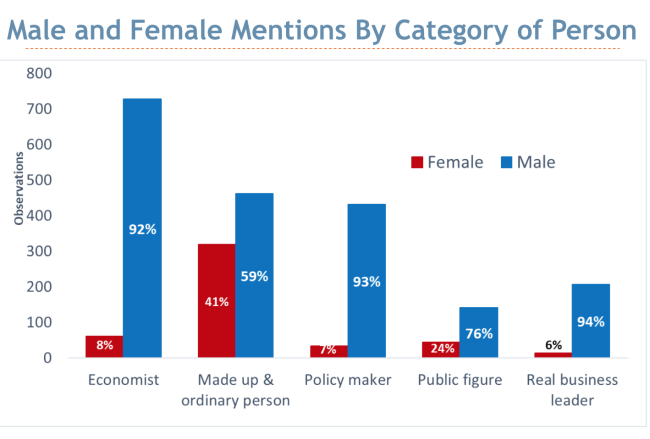

A study of leading introductory economics textbooks, presented last week at the annual meeting of the American Economic Association, found that three-quarters of the people mentioned in the books (77 percent), real or imagined, are male. Some 18 percent of mentions are female and 5 percent are gender neutral.

The real-life economists mentioned tend to be men, but not because they’re key historical figures, according to the study. And when these textbooks do mention women in relation to economic principles, they’re more passive than their male counterparts and more likely to be involved in food, fashion or household tasks. Men are more likely to be appear in relation to business or policy.

“In any kind of teaching material that we’re creating as instructors, we’re using the body of knowledge we have about the world we’ve experienced -- and that means that teaching materials, almost by definition, are backward-looking,” said the lead author, Betsey Stevenson, associate professor of public policy and economics at the University of Michigan.

Reasonable people might disagree as to whether that’s a good, bad or neutral proposition, Stevenson said. But if instructors want their teaching materials to instead be “forward-looking,” she added, they should craft and choose examples that describe “the world their students are going into -- not the world they’ve lived in the past.”

Such an argument could be made about teaching tools in many fields. But the last year has seen a particular focus on gender dynamics in economics. One study found that female economists write more readable papers than their male peers but take significantly longer to get published, for example. A separate paper found that the field has different standards for men and women when it comes to co-authorship, and that the standards favor men. Yet another study found that a popular online forum for economists is, well, pretty sexist.

Stevenson said economics as a discipline needs to do more “to understand why women aren’t attracted to the field and why the field is not attracting women.” But it’s already clear from the existing literature that when students don’t see themselves reflected in role models and examples, “they stop and think, ‘Maybe this isn’t for me,’” she said. As an example, she cited a recent study saying that a female role model intervention program in introductory economics courses had no impact on male students but significantly increased women’s likelihood of expressing interest in majoring in economics and taking future courses in it.

Stevenson conducted her study with Hanna Zlotnick, a master of public policy candidate at Michigan. They included seven top principles of economics textbooks in their study presented at AEA, and have since incorporated an eighth book. The original textual analysis found that 30 percent of the people mentioned in textbooks are economists. Among those, men outnumber women 12 to one. No female economist appears in every book studied.

Some of that makes sense. Economists, historically, have tended to be men. But even when Stevenson and Zlotnick excluded all economists from their analysis, 70 percent of people mentioned were still men. Analyzing only examples of ordinary, made-up people -- where textbook authors have the most creative leeway -- 59 percent of gendered examples were male. Some 15 percent were explicitly written to be gender neutral. The rest were women.

Few female business leaders are mentioned -- just 11 across seven books. Six percent of policy makers listed in the books are female. Federal Reserve Board Chair Janet Yellen accounts for 55 percent of those mentions.

Stevenson disclosed that she’s under contract to write an economics textbook by one of the publishers considered in her study (though it didn’t get special treatment, she said). She’s also preparing her study for publication, to include the eighth textbook and some feedback to criticism she’s received since AEA.

N. Gregory Mankiw, the Robert M. Beren Professor of Economics at Harvard University (and a former professor of Stevenson’s), for example, has questioned on his blog whether Stevenson drew the right conclusions from her data. Namely, Mankiw -- who wrote one of the textbooks studied -- asked whether the findings really expose textbook authors' implicit bias.

Worldwide, just 4 percent of CEOs of Fortune 500 companies are women, Mankiw wrote. So is Stevenson’s finding that just 6 percent of “real business leaders” mentioned in textbooks are women really an “underrepresentation of women in textbooks or an accurate reflection of reality?”

Similarly, he said, policy makers mentioned in texts are most often presidents or Federal Reserve chairs. “Historically, only one woman has been a member of this group. Economists mentioned in texts are most often important historical figures (Smith, Ricardo, Keynes) or prominent modern economists, such as Nobel laureates. Once again, 8 percent is higher than for the population being sampled.”

To be sure, he said, “the role of women in society is changing, and in some circles there is some bias. But measuring the amount of bias is hard.”

Stevenson said Thursday that she’s since found that textbooks still underrepresent women as CEOs. And instead of Adam Smith and other historical figures, she said, the vast majority of male economists mentioned are “alive and well.”

While much bias on the part of textbook writers appears to be implicit, most if not all writers make conscious choices to include sports and other contemporary references to engage students, she said. So part of that decision-making process can also be about engaging women with meaningful examples and role models.

"There are those with more libertarian perspectives who will shrug their shoulders and say, 'If they want to come, they can.' But that fails to recognize there are defaults to the ways we're attracting some students and not others."