You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

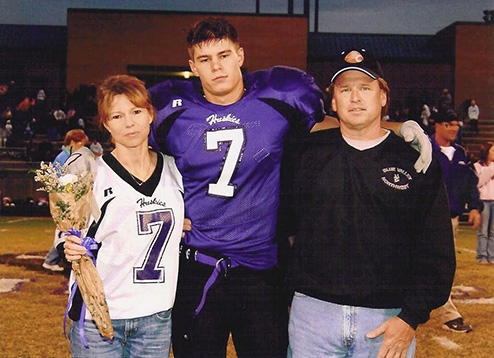

Zack Langston

Concussion Legacy Foundation

Zack Langston, 26, shot himself in the chest so his brain could be studied.

The former Pittsburg State University football star ended his life nearly four years ago, convinced the repeated collisions he endured at practices and games had resulted in memory loss, paranoia and his suicidal tendencies. Langston's story is detailed in court filings, part of a lawsuit by his family against the National Collegiate Athletic Association and the athletic conference that Pittsburg belongs to, the Division II Mid-America Intercollegiate Athletics Association (MIAA).

Langston turned out to be right -- posthumously, he was diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, a brain disease often found in athletes who have experienced frequent blows to the head. One study of professional football players’ brains found nearly all of them suffered from CTE -- 110 out of the 111 former National Football League players’ brains studied exhibited the disease.

Many others besides Langston's family have similarly sued the NCAA, seeking damages for former players and alleging they still bear the effects of concussions.

Last year, the Associated Press reported that the NCAA faced 43 lawsuits filed by Edelson PC, the firm representing Langton’s case. Subsequently more than 100 plaintiffs have joined the lawsuits against the association and sometimes against conferences or individual institutions. The legal challenge is part of a broader effort to pursue a class-action suit against the NCAA and to force it to pay for medical expenses for treating brain injuries. Four sample cases have been selected.

The case still needs to be classified as a class-action suit and remains in its early stages.

Academics and experts have pondered whether the pressure will eventually lead the NCAA to endorse major reforms.

In 2010 the NCAA forced all its member institutions to develop concussion management plans, with a stricter set of standards for colleges to use in evaluating and treating concussions. Prior to that the rules were inconsistent, said Scott Anderson, the president of the College Athletic Trainers Society and head athletics trainer at the University of Oklahoma.

Anderson said conversations about concussions and the need to address them shifted in the early 2000s, following NCAA-funded research from Kevin Guskiewicz, director of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill's Matthew Gfeller Sport-Related Traumatic Brain Injury Research Center, and Michael McCrea, director of brain injury research at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Their study, published in 2003, served as a launch point for other research, the NCAA said, though the federal court filings note many other studies prior to Guskiewicz and McCrea’s.

Langston’s lawsuit calls the NCAA concussion-management practice “flawed” in that it requires athletes to self-diagnose a concussion and give consent to continue playing when they may be unable to competently make that decision.

Such litigation may prod the NCAA to tweak concussion rules, said Michael McCann, associate dean for academic affairs at the University of New Hampshire School of Law and director of its Sports and Entertainment Law Institute.

McCann pointed to the six-year, $1 billion settlement by the NFL to former players who were proven to have lingering problems from concussions. The league introduced harsher rules following the settlement, with teams facing fines of hundreds of thousands of dollars if they don’t remove players from games after they are concussed.

The NCAA in 2014 paid $75 million to settle a concussion-related class-action suit -- $70 million of which will be used for a 50-year medical monitoring service for athletes and another $5 million for research and treatment of concussions. But this money is meant only to identify symptoms associated with concussions or brain injuries for athletes -- it's not for treatment.

The federal judge in that case declined to exempt the NCAA from future class-action suits, leading to the continued filings against the association and its conferences, though the colleges aren’t generally named as plaintiffs because of the complex liability issues associated with suing a public institution.

Representatives from the MIAA, named as a plaintiff in Langston's lawsuit, declined to comment, as did the college president who leads its advisory board, Bob Vartabedian, president of Missouri Western State University.

Risk for Conferences

Also at issue is the expense of these lawsuits.

While insurance policies can front the payouts on concussions, should universities prove to be a continual risk, carriers could decline to cover them, said Christian Dennie, a lawyer and partner at Barlow Garsek and Simon, who specializes in sports law cases.

Not every conference has the NCAA's deep pockets, either. Per its federal 990 tax form for 2015, the MIAA has about $687,000 in assets.

“The more lawsuits that are filed, we’re going to start seeing exclusions in insurance policies, and that would create problems,” Dennie said.

While suing the NCAA could result in better funding for protective gear during games -- many experts cite improved helmets and technology as possibilities -- McCann said lawsuits can’t eliminate the dangers of football.

“I think we have to be inherently realistic that the game of football is dangerous,” he said. “I think that’s the sobering part of the story. There isn’t a solution to the health issues that have come up.”

Many researchers liken the hits football players take to being subjected to repeated car accidents.

Driving a car into a wall at 25 miles per hour without a seatbelt would result in about 100 g’s -- one g is equal to the force exerted by gravity on a body at rest -- to a person's head as it hit the windshield, according to Guskiewicz’s research.

Almost all of the football-related hits to the head exceed 20 g’s, and per Guskiewicz, if a player took two hits of more than 80 g’s in a practice, they would have experienced the equivalent of two car crashes.

Much more expansive research on concussions remains ongoing in an unusual $30 million partnership between the NCAA and the U.S. Department of Defense -- the reason for the collaboration being that the military grapples with many of the same injuries, said Steve Brogilo, who helps lead the NCAA and the Defense Department’s CARE Consortium, which stands for Concussion Research, Assessment and Education.

Brogilo is also an associate professor of kinesiology at the University of Michigan and director of its Neurotrauma Research Laboratory.

Speaking last month at the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics meeting, Brogilo said 50 percent of concussions occur before a season begins. Thus far, the consortium has studied about 2,500 concussive injuries, he said.

“Banning the game is absurd,” Brogilo said. “Practices are the No. 1 place to focus. You can change practice rules easily -- changing game rules becomes much more complex.”

Banning Football?

Challenges to the institution of football, however, are a small but growing force.

Three professors at the University of San Diego recently introduced a resolution in their department for the college to ban football.

It was voted down, 50 to 26, with 30 abstentions. Had it passed, the measure would have moved to the full faculty of the university for consideration.

Ken Serbin, a professor of history who helped draft the resolution, said his interest in concussions stemmed from his work with Huntington’s disease, a genetic brain disorder that his mother died from and for which he carries the genes.

He has thrown galas to raise money to research and combat Huntington’s, and one of his donors was the Chargers, the NFL team now based in Los Angeles. When he learned about the effects of CTE on the players, to Serbin it seemed like a contradiction that a team would raise money to ending one brain disease while simultaneously overlooking another.

During the faculty vote on his resolution, he said many professors didn’t focus on the science that he and his two other colleagues presented, but rather defended football on its cultural merits. Many didn’t grasp that a concussion is not like other injuries, Serbin said. One professor compared it to a rotator-cuff tear. But while the body can recover from that after a certain period, he said, the brain isn’t like a broken bone, and damage can be permanent. Some of his colleagues' view of brain damage was “unsophisticated,” he said.

“The old idea of ‘having your bell rung,’ as we called concussions -- that’s gone,” he said. “We are at a new level of brain science.”

Serbin was particularly astounded by the number of abstentions. Though he said he couldn’t pinpoint why faculty members voted the way they did without interviewing them, he guessed many have concerns about football but didn’t want to take on such a popular sport.

One professor approached Serbin after the vote and said the presentation against football was convincing, but that the professor didn’t want to discontinue it because his brother played college football and the brother would be “disappointed to hear that the university was canceling it.”

“It’s a sacred cow, football is,” Serbin said. “It really is for many people America’s new religion. People used to make church attendance their primary Sunday activity, and now people’s primary Sunday activity for many, many Americans is watching a football game. It’s been very successful in establishing itself in our culture as this new item of worship.”

He said though this attempt failed, Serbin wants this to serve as a “spark” for those at other institutions.

Serbin’s story is somewhat unique in that although few professors have called for football to be banished entirely, decades ago a faculty-led campaign essentially killed the formerly beloved sport of collegiate boxing.

Faculty at the University of Wisconsin at Madison voted to ban the sport after a well-liked student, Charlie Mohr, died following a fight in 1960. He first went into a coma, then passed away days later. Though proponents of boxing adamantly defended it, the NCAA canceled its boxing tournament, and the sport's popularity faltered.

This year, Occidental College, a Division III institution, scrapped its football season entirely in October amid health concerns for players. Despite being in a lower division, the move was significant. Occidental plays in the Southern California Intercollegiate Athletic Conference.

President Jonathan Veitch said in a statement at the time there were not enough healthy players to field a team.

"No one wanted or expected the season to end this way. Making this decision now provides needed clarity to players, their parents, coaches and other SCIAC members,” he said in his statement. “After canceling two of our first five games because of a depleted roster, including last weekend's homecoming game, the need to address the viability of the season became unavoidable."