You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Leading into September, conservative provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos had built up his near week-long event at the University of California, Berkeley, as a monumental moment, one that would help relinquish the “leftist” grip on academe. The ex-Breitbart editor touted a contingent of speakers from the more extreme edges of the right -- including Ann Coulter, who intended to appear on the campus in April but never followed through, and Steve Bannon, the controversial now former adviser to President Trump.

Yiannopoulos posted on Facebook an image of a crowd of students, conjuring the idea that a similar throng would descend on the university known as the birthplace of the Free Speech Movement. He declared, “It’s time to reclaim free speech at UC Berkeley and send shock waves through the American education system to every other college under liberal tyranny.” His press conference the day prior to the event on Sept. 24 was titled “eve of battle.”

The university planned accordingly. It had already had been caught off guard in February with Yiannopoulos’s first planned speech. Protests turned violent, with fires lit and stones hurled at law enforcement. Security was escalated for the so-called free speech week, with the university spending at least $800,000, but likely far more, the bulk being additional police presence. Invoices are still rolling in, a Berkeley spokesman said.

Yiannopoulos spoke for no more than 20 minutes -- far cry from the war scene he invoked.

The gathered crowd dispersed.

Other speakers he had promised never showed.

The university called his appearance largely “uneventful” and “brief.”

By every account, Yiannopoulos’s strike against what he considers the academic establishment fizzled, but it cost the institution just shy of $1 million -- more than what it spent on similar safety measures in three fiscal years combined. Less than two weeks before that, Berkeley had spent about $600,000 to ensure right-wing writer and commentator Ben Shapiro could address campus.

Next week, white supremacist Richard Spencer will speak at the University of Florida. Officials there estimate a drain of at least half a million dollars on the institution’s coffers, also on security.

Representatives from public institutions said they are meeting their constitutional obligation to provide a space for these speakers, but they remain relatively lost for a long-term strategy for paying for security. Colleges and universities can adjust after these appearances and consider trimming costs, but none interviewed have settled on any financially viable plan. And, likely, the tours of these political lightning rods will not slow.

“We need to examine this,” said Dan Mogulof, a Berkeley spokesman. “There’s a delicate balance that has to be maintained. There are commitments -- legal ones, constitutional, ethical, moral, programmatic and operational -- all of those are factors, all of those elements have definitely [been] impacted by recent events.”

Though inflammatory speakers are nothing new on campuses, the tactics of Yiannopoulos, Coulter and others -- deliberately targeting colleges and their students -- seems to have intensified in the last year. Notably, in December 2016, Spencer, who helped coin the term “alt-right” to describe a movement characterized by racist, anti-Semitic and white nationalist views, came to Texas A&M University to launch a nationwide series of visits to colleges. The university shelled out about $60,000 for his appearance, said Amy B. Smith, Texas A&M spokeswoman -- not cheap compared to other events there, but not close to the hundreds of thousands other universities have paid, perhaps because it was one of the first.

“There were some of these things. This was one of the largest and most controversial out of the gate compared to other schools,” Smith said. “There were some before that, but all eyes were on us to get it right.”

Nine months later came Charlottesville, Va.

Spencer once again roiled a campus, the University of Virginia, in August, but this time he brought with him torch-wielding followers, who marched the grounds chanting Nazi refrains. One of the white nationalists is now charged with driving into a crowd in the city and killing a counterprotester the next day.

Afterward, Spencer would try to rally on campuses again -- among them Texas A&M and the University of Florida. They rejected him, with the institutions citing security concerns, in part because organizers of his prospective events had publicly linked them to the Charlottesville protests. “Today Charlottesville, tomorrow Texas A&M,” a press release read. Lawyers have said in interviews the institutions had legal grounds to block Spencer, though Florida eventually reconsidered.

To avoid a repeat of Charlottesville, college leaders have likely been overly cautious and want to ensure and pay for adequate security, said Kevin Kruger, president of NASPA: Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education.

“The penalty for underpreparing is significant,” Kruger said. “If there are injuries, and there’s a reputational risk to campus, if you evaluate and you ask, ‘Why didn’t you do that?’ and the answer is ‘we don’t know’ or ‘it was too expensive,’ well, that’s not an appropriate response.”

UVA’s postmortem report on the rally in August found that the city and university didn’t have enough officers to handle the demonstration and that certain policies weren’t enforced that would have curtailed the white nationalists' activities.

The University of Florida, meanwhile, has prepped significantly for Spencer’s Oct. 19 talk -- and done so quite visibly. It published a question and answer page online that address everything from how much the event will cost to whether buildings will be shut down and the reasoning behind allowing him on campus.

Spokeswoman Janine Sikes refused to break down the more than $500,000 in expenditures, saying the details could reveal confidential security information. She cited exemptions in state public records laws that allow the institution to withhold such information. Sikes also declined to set up further interviews -- “in the throes of craziness, this is not something we’re going to talk about.”

But she said that the University of Florida's president believes that it’s important to permit outsiders to rent campus facilities. Few such large-scale venues exist in Gainesville, where the university is located, Sikes said.

“This university cannot sustain these kinds of costs going forward; some kind of decision has to be made on how that gets weighed,” Sikes said. “It hasn’t been argued and weighed at this point, and it’s an obvious question that needs to be answered.”

Colleges also can’t pass the bill along to the speaker, either. A Supreme Court case, Forsyth County, Georgia v. The Nationalist Movement, decided in 1992, ruled that the government can’t charge unreasonably high security fees -- it’s possibly a way to restrict speech based on its popularity.

“Speech cannot be financially burdened, any more than it can be punished or banned, simply because it might offend a hostile mob,” Justice Harry A. Blackmun wrote in the case.

Kruger, of NASPA, said institutions face a budgetary dilemma: paying for both their core educational mission and the new expense of these costly outsiders -- “it’s an expensive proposition, and there’s no easy answer.”

Institutions in theory could adopt some sort of policy that would cap spending for these types of events, but drafting a legally sound one could prove difficult, said Adam Goldstein, a lawyer and legal fellow with the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, a higher education-centric free speech watchdog group.

Public universities have restricted speakers, setting rules, for example, that forbid outside parties from renting a building without the sponsorship of a student group. Texas A&M added this requirement after Spencer’s appearance last year. Many speakers, though, however extreme, can often find a student group to issue an invitation.

A financial ceiling would need to be objective with regard to potential speakers, and be reasonable, narrow and defined, Goldstein said. Complicating matters is what is considered “reasonable,” he said.

“There are standards that can determine the likelihood of a disruption. Insurance companies have a pretty big list of these -- presence of alcohol, motorized vehicles -- any one of these might change the analysis for how many officers you might need,” Goldstein said.

Determining the number of personnel needed for an event isn’t formulaic, so nor will the cost be, said William Mathews, assistant chief of police for city of Auburn, Ala., which provides law enforcement for Auburn University. Spencer spoke there in April, backed by court order after the institution had canceled his talk and a student sued on Spencer's behalf.

Mathews said he could not identify how much was set aside for security and requested a reporter file a public-records request. He also said he could not discuss how many officers were needed for the event, only that additional men and women were pulled from agencies at all levels -- local and state. Auburn also relied on Federal Bureau of Investigation information on possible threats, he said.

Before Spencer’s arrival, the university anticipated and paid for the worst-case scenario, though that never materialized, Mathews said. Officials had heard that additional buses would arrive from both from the state’s capital and Atlanta -- they never did.

“You plan for the worst-case scenario based on what you know at the time,” he said. “Maybe you are going overboard and [will] not need them, but you might need them badly.”

Auburn’s event did not result in broad property damage or bloodied fists (though at least three people were arrested) -- a relative success, Mathews said. The officers allowed those supporting Spencer and those protesting him to mingle, to scream in the other’s faces to release a bit of tension -- but it’s not something he would advise in the current climate.

“The mood has changed,” he said.

Because most institutions, such as Florida and Auburn, hesitate to release detailed security spending because it could compromise future events, what exactly they’re buying can be a little unclear.

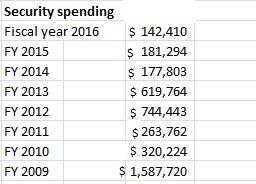

Berkeley though, offered a deeper analysis of costs associated with Yiannopoulos’s visit in February and preparation for Coulter’s planned April visit (see table) that indicate more and more is being pulled from the university budget -- and that policies are not designed to accommodate what Mogulof called a “quantum leap” in the money needed for these speakers.

The university spent almost $269,500 for Yiannopoulos and more than $664,220 on Coulter, largely on outside police.

Mogulof stressed, too, that the safety costs in the current fiscal year, which began in July, will far outnumber previous years -- and it’s only October. In fiscal 2016, for instance, Berkeley spent a little more than $142,000. Typically it sets aside about $300,000 in contingency money for security, Mogulof said.

In fiscal 2009, the university spent $1.5 million, but that record will likely be broken. That’s when the university accounted for the money spent on dealing with a sit-in for campus oak trees, in which protesters climbed among their branches to prevent them from being cut down to make way for a new athletic center.

Now the costs are being divided between Berkeley and the University of California System’s Office of the President, but Mogulof wasn’t sure of the split.

A commission will be formed to study the university response to controversial speakers, Berkeley Chancellor Carol Christ announced last month -- and it could examine the option of a policy to limit spending, Mogulof said. For now, the university has reached a degree of calm as procedures require an eight-week notice for any campus speaker -- no one is in the pipeline.

In the interim, the university will consider different possible venues that could hold the possibility of reduced security for the future, Mogulof said, declining to elaborate further.

In the interim, the university will consider different possible venues that could hold the possibility of reduced security for the future, Mogulof said, declining to elaborate further.

Berkeley owns buildings away from the main area of campus that could accommodate speakers, though historically some have publicly scolded universities for attempting to hide them away from students.

Mogulof also said that not every speaker will generate the same buzz -- liberal-leaning figures simply tend not to attract the same level of divisiveness, he said, and some speakers come with a more insidious mission, to ignite campus fury rather than a dialogue. Shapiro, spoke, took questions and simply left, Mogulof said -- not so with Yiannopoulos.

“Spending -- it’s really a Band-Aid, it’s spending on security that’s a symptom of a deeper and more profound problem,” Mogulof said. “For many of these speakers, it’s the backlash they generate. The security is necessitated not by the words themselves, but reaction to the rhetoric and the speaker.”