You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

More than a third of all college students move from one college to another at least once in their academic careers, and more institutions -- public and private alike -- count on transfer students to fill their classes. Which makes it all the more perplexing, and problematic for colleges and students alike, that the path students must follow to move from one institution to another is riddled with potholes and roadblocks that stop many of them in their tracks.

A trio of new reports from different sources illustrate just how vexing the transfer process is. A Government Accountability Office study released Wednesday provides baseline data both about the number of students who change colleges (one in three) and about the cost to those students and to taxpayers when those students lose roughly four in 10 of the credits they accumulated at their first institution.

The National Student Clearinghouse's “Tracking Transfer” report broadens the lens to show that while community college students who transfer to a four-year institution are far likelier than all two-year-college students to earn a bachelor's degree (42 percent to 13 percent), those from low-income backgrounds who transfer to nonselective or rural four-year institutions are at a severe disadvantage.

And a report from the Campaign for College Opportunity calls the much-traversed transfer route in California a "complex and costly maze" that forces those who navigate it successfully to spend tens of thousands of dollars more to earn a bachelor's degree than do students who start out at one of the state's (more expensive) four-year universities.

"The confluence of these studies confirms that this is a problem, and that transfer students are one of most abused [groups of] students," said Davis Jenkins, a senior research scholar at the Community College Research Center at Columbia University's Teachers College. "They haven't been well served by most institutions, two-year and four-year alike."

The Transfer Landscape

Students change colleges for lots of reasons: shifts in their educational needs or goal, dissatisfaction with the original institution, changes in life situations, and the like. And for perhaps the largest chunk of transferring students -- those who enroll at community colleges with the goal of eventually attaining a four-year degree -- changing institutions is a central, purposeful objective.

As the GAO study shows, a significant number of students -- 35 percent of all students who started college in the 2003-04 academic year, according to the Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study -- make such a change. The vast majority of those, roughly 75 percent, started at a public institution, and about two-thirds transferred from one public to another.

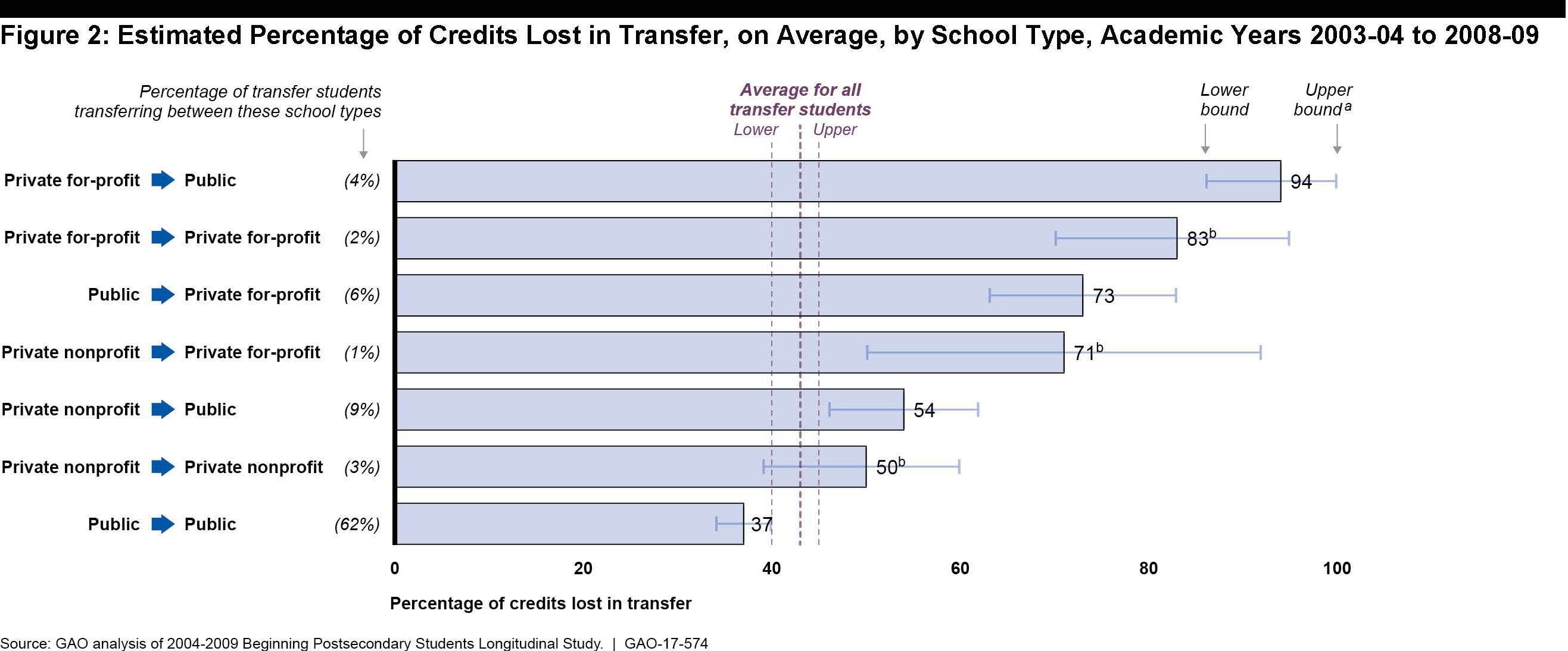

On the whole, public institutions within a state are thought to have the best records on transfer of credit, since they are presumably more likely to work in concert with one another, to have common goals or to have either voluntary cooperative agreements or statewide policies requiring cooperation. And in fact, the GAO estimates, students transferring between two public institutions do on average lose fewer academic credits in the process than do those crossing sector lines, as seen in the graphic below.

But the average transfer student lost a full 43 percent of their credits, roughly 13 credits, or a semester’s worth, the GAO estimates. The reasons why credits do not transfer vary: mismatches in the curricula of the different institutions, too many of the courses do not apply to a major, snobbery on the part of the receiving institutions, poor choices by students (sometimes based on inferior advising).

The costs are significant, and not just to the students who may have to repeat course work. Given that half of the students who transferred in the sample the GAO studied had received Pell Grants, and nearly two-thirds received federal loans, "credits lost in a transfer also can result in additional costs for the federal government in providing student aid," GAO wrote. "The government’s costs may increase if transfer students who receive financial aid take longer to complete a degree as a result of retaking lost credits."

The California study offers a look at how the issues play out in one state (but a mammoth one). It reaches a similar finding -- that 38 percent of community college students transfer within six years -- and estimates that those who transfer spend an estimated $36,000 to $38,000 more to get their bachelor's degrees than do students who start out at a California public institution.

It spreads the blame for the problem widely, citing:

- "A broken remedial education system that traps students in non-credit-bearing courses."

- Campus-level faculty autonomy that allows a "lack of curricular alignment with other campuses," often within the same system.

- A "decentralized higher education system" in which the state's three major systems "operate as distinctive entities with no mandate for cooperation."

- "Too many choices in general education with inaccessible information for students to make informed decisions."

- State budget cuts that have restricted the availability of courses at community colleges, causing delays in the time to transfer.

- A ratio of 615 students for every community college adviser or counselor, resulting in "students guiding themselves or receiving inconsistent guidance."

“Students are caught in the middle of battles between the systems, colleges and faculty, and the costs are high," said Michele Siqueiros, president of the Campaign for College Opportunity. "Every day spent fighting over educational turfs, we fail to clear up the transfer maze and we lose the talented students we urgently need for our work force and economic stability.”

The third report, from the National Student Clearinghouse, provides not just data about the national picture for transfer students but a framework by which individual states and institutions (two-year and four-year) can judge their own success -- and be judged.

The clearinghouse study, which follows a 2016 study that laid out the framework, provides data on how successfully students transfer out of community colleges and into four-year institutions.

For instance, it finds that while 33.6 percent of all transfer students leave community colleges having earned a certificate or associate degree, those numbers are slightly higher at two-year colleges that are primarily occupational (35.8 percent) than primarily academic (32 percent). And while 42.2 percent of all students who transferred from a community college ultimately earned a bachelor's degree, only 35.8 percent of those from the lower socioeconomic quintiles did so, compared to 44.7 percent of those from the upper two quintiles. (Students who were enrolled full-time in a community college, unsurprisingly, earned bachelor's degrees at a rate of 61.4 percent, compared to 8.3 percent of those who studied exclusively part-time.)

The clearinghouse report assessed four-year institutions on similar grounds; 54.5 percent of students who transferred to very selective institutions completed bachelor's degrees, compared to 21.1 percent of those at nonselective colleges, and transfers to suburban institutions were likelier to graduate (38.3 percent) than those at urban (35.4 percent) or rural institutions (29.3 percent).

The days when only a small number of institutions might have worried about transfer students are gone, said Jenkins, of the Community College Research Center. "When we talk to students who've tried to transfer, it makes me want to cry, and when we talk to legislators, people are pissed off," he said.

And with many if not most regional public universities and private nonprofit colleges struggling with enrollments, "colleges are missing a huge business opportunity to invest" in making sure they are clearing pathways for transfer students, he said.

"They're failing to recognize who their students are," Jenkins said. "A lot more of them are getting most of their students through transfer, and they have to do a better job" of working with community colleges to smooth out impediments. "They should work with their suppliers like any other business that’s supplier dependent."