You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

WASHINGTON -- Views on higher education are becoming increasingly hostile among certain Americans, and scientists say some of the blame rests with them. They aren't apologizing for their work, but for their failure to promote public understanding of it.

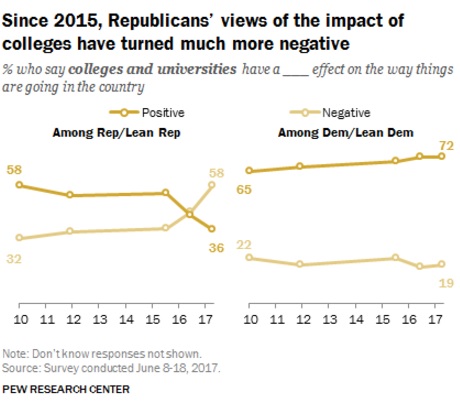

Discussion about community outreach and proving research’s positive impact on society dominated much of the discussion at the State of American Science forum held in Washington Wednesday, organized by the Science Coalition and the Association of American Universities. The concerns were raised by the 12 provosts and vice presidents of research from universities across the country, especially in light of a recent Pew study finding that 58 percent of Republicans see colleges as having a negative impact on the country’s direction, a dramatic uptick among members of a party that controls the presidency, both chambers of Congress, the majority of statehouses and the majority of governors’ mansions.

“In particular, I think universities and colleges have to step up in ways that scientists have also not stepped up, just really [to] communicate,” said Eric Isaacs, vice president for research, innovation and national laboratories at the University of Chicago.

“I think we have not done a great job,” he said. “I think we’ve sort of assumed, at the universities, that people understood what we’re doing. And we think about education, people understand that, but less so [do] they understand the impact our research has.”

In many ways, researchers are indeed engaging more. Gary Ostrander, vice president for research at Florida State University, said that for a position like his to have a dedicated communications staff was unheard-of in the past, but the advent of social media and the internet have changed that. Still, he said, the gulf between higher education and its perception among the GOP was concerning.

“I think the messaging is important, but I also think the audience is important,” said Robert Clark, provost and senior vice president for research at the University of Rochester. “I think one of the things that we, as institutions, have to be cognizant of is that the general population doesn’t always broadly understand what we are communicating.”

The various vice presidents agreed that, often, research isn’t disconnected from the public's interests, nor does it require vast scientific knowledge to understand. However, its practical, everyday applications -- whether to business, agriculture or medicine -- aren’t being highlighted well enough. Isaacs pointed to the partnership between the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and Life magazine in the 1960s -- bringing photos of humankind’s new frontier to the masses -- as perhaps the best example of outreach and engagement done right.

To be fair, only so much is in the control of scientists and researchers. The past few years have seen a flare-up in liberal and leftist student activism -- often reported heavily on conservative media outlets, which, like their liberal counterparts, have flourished and expanded in number online.

This makes it easier for culture wars -- real or perceived -- whether they're about free speech, diversity and multiculturalism, racism, or political correctness, to go viral. Elitism, often tied to academe, has been a polarizing political force around the world as populist waves have made headway -- and produced victories -- in elections in ways previously unseen.

“Americans are not that special,” Denis Wirtz, vice provost for research at Johns Hopkins University, said about the embrace of populist political messaging during the 2016 election. But if researchers can’t clearly come up with answers for colleges' contributions to society, others will.

“The current administration is providing easy answers, such as ‘Let’s cut indirect costs,’” he said, referencing the White House’s proposed cuts to overhead costs needed to support research that have been widely panned by the science leaders and that were rejected in a draft of a House of Representatives appropriations subcommittee bill.

"It’s a mistrust of universities, and I think compounding factors are high-cost universities, graduates going into the work force and not finding jobs, and for-profit universities that have really created all kinds of issues.”

On the other hand, colleges have always been hotbeds for politically tumultuous movements. If there’s so much negativity, shouldn’t science and research’s benefits -- especially in ways that could find conservative sympathies, such as their contribution to national security and the private sector, as well as the communities they’re physically located in -- be able to push back against the negative rhetoric?

“I think scientists have tended to roll their eyes when people say, ‘I don’t believe it,’ rather than roll up their sleeves,” Wirtz said. “[But now] I see faculty come to my office, come to our federal relations office, asking, ‘How do I communicate to Congress, how do I communicate to people?’ There is a sea change.”

Budget Cuts, Travel Ban

Largely, the various vice presidents weren’t too worried that Trump’s budget would be adopted, although if it was, they made clear that the proposed cuts would severely harm research funding. The real budgeting power, however, comes from Congress, and institutions are more hopeful on that front.

“Yes, we’re concerned about the cuts in the EPA” and the Department of Energy, said Stephen Cross, the executive vice president for research at Georgia Tech. “But I think science is going to be well funded. What a wonderful opportunity for us to start communicating the impact of what we’re going to do over the next four years. Shame on us if we don’t do it.” (Early indications on biomedical research funding came Wednesday from the House of Representatives’ appropriations subcommittee that oversees health programs.)

Cross added that an unseen benefit to the Republicans’ preference toward cutting regulations could be that burdens on universities and research are lifted.

While the research on climate change might take a hit during an administration that pulled out of the Paris climate accords, the EPA and the Department of Energy still have research pursuits, such as the DOE’s supercomputing sector. Research, though it might face increased resistance, can still prove not only its own worth, but that of universities, those gathered said.

“Imagine if the Manhattan Project were done by [private] industry,” Isaacs said. “It just would not have happened the way it did -- you’re not going to get a private company to mount that kind of massive campaign.”

Mood around the Trump administration’s travel ban was grim, although many at the forum said its actual effects are likely to be seen in the fall. Regardless of how many scholars, researchers and students are actually barred from enrolling in the U.S. because of the ban, the biggest concern was the atmosphere it might create.

“The science we do is very international,” Isaacs said. “If we stop allowing people into this country, it’s going to feel like we’re trying to withdraw from the world.”