You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Blackboard

Much of the debate about accessibility issues in higher education in recent years has focused on audio and video -- take, for example, the high-profile lawsuits against prestigious institutions such as Harvard University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of California, Berkeley.

But new data from Blackboard show that the most common types of course content that students use on a daily basis -- images, PDFs, presentations and other documents -- continue to be riddled with accessibility issues. And while colleges have made some slight improvements over the last five years, the issues are widespread.

The findings come from Ally, an accessibility tool that Blackboard launched today (the company in October acquired Fronteer, the ed-tech company behind the tool). Ally scans the course materials in a college’s learning management system, comparing the materials to a checklist based on the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 AA, developed by the World Wide Web Consortium’s Web Accessibility Initiative. If any issues arise, the tool flags them and suggests accessible alternatives.

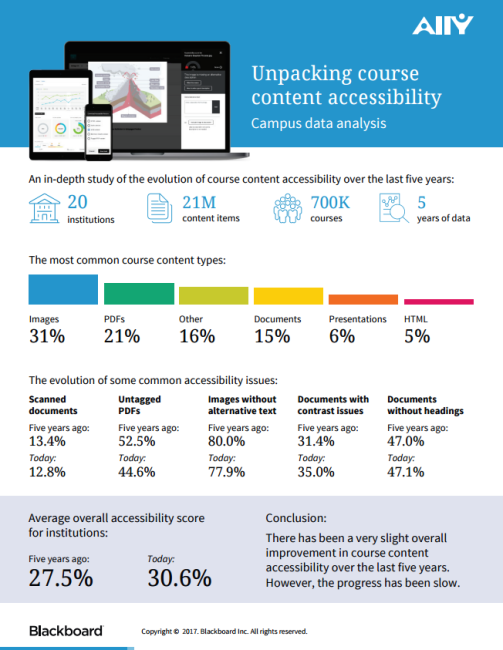

As part of the launch, Blackboard released a brief look at how course content accessibility changed between 2012 and 2017. Although the data come from only 20 institutions, the analysis covers 21 million course content items used in 700,000 courses.

Blackboard did not say which 20 institutions were included in the study but added that they were selected to provide a “good mix” in terms of geography and Carnegie classification in order to “provide insight into most of North American higher education.”

The findings paint a mixed picture. On one hand, colleges are using fewer scanned documents (12.8 percent of all documents, down from 13.4 percent), untagged PDFs (44.6 percent of all PDFs, down from 52.5 percent) and images without alternative text (77.9 percent of all images, down from 80 percent) than they did five years ago. Those issues make it difficult, if not impossible, for screen readers to convert the files into text. On the other hand, the number of documents with contrast issues or without headings has increased slightly.

The average overall accessibility score -- which is intended to give colleges a high-level estimate of the accessibility of their course content -- has risen from 27.5 percent in 2012 to 30.6 percent. That does not mean that less than one-third of course materials are accessible to people with disabilities, however. The accessibility issues flagged by Ally are weighted differently. For example, a scanned document that is completely unreadable to a blind student has a greater impact on the score than a document with contrast issues, Blackboard said.

“We are seeing over the last five years a very slight improvement, but over all the improvements are small,” said Nicolaas Matthijs, a product manager at Blackboard who helped develop Ally. “We’re still far away from where we ideally want to be.”

In a statement, the National Federation of the Blind also lamented the “glacial progress” seen in the data.

“These findings confirm that there is definite progress in the higher education community with respect to providing content that is nonvisually accessible,” Chris Danielsen, director of public relations, said in an email. “They also demonstrate that institutions are becoming more educated about accessibility and its importance. However, this progress is extremely slow, and all the while blind students continue to struggle.”

The NFB is one of several organizations pushing for the passage of the Accessible Instructional Materials in Higher Education (AIM HE) Act, which would develop and promote voluntary accessibility guidelines for course materials.

Matthijs said the data don’t properly capture the fact that an increasing number of colleges are taking steps to make course content accessible to students with disabilities (although some of the institutions may be doing so because of the looming “threat of some sort of legal action,” he said).

“As accessibility has become a bigger issue, we’ve seen an average improvement, which in many cases can be tied back to institutional initiatives,” Matthijs said. “But the progress has been slow.”

Margaret Price, associate professor of English and director of disability studies at Ohio State University, said in an email that she is concerned that the gap between the colleges making an effort to address accessibility issues and those that aren’t may be widening.

“We may be perceiving the emergence of a new digital divide -- a divide between those who create content that is accessible from the start … and those who assume that accessibility must be extremely difficult or expensive, and not worth the effort,” Price said. “That's simply not true, but it's a myth that I seem to be running into with increasing frequency -- even as I am also running into more and more professors and students who are excited to think about access in creative and generative ways.”