You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The Education Trust

Only 41 percent of black students who start college as first-time freshmen earn a bachelor’s degree within six years -- a rate more than 20 percentage point below that of white students.

While that’s the national average, a new report from the Education Trust, a nonprofit organization that advocates for minority and low-income students, suggests that the average gap at individual institutions is just two-thirds that wide. And that means if higher education collectively is going to close the completion gap, it will take more than just boosting graduation rates on individual campuses. Highly selective colleges with high graduation rates must also enroll more black students, the report concludes.

“If you close all institutional gaps, you’re still going to have a pretty substantive national gap,” said Andrew Nichols, Education Trust’s director of higher education and the report’s lead author. “You have very few black students going to highly selective institutions, and you have a lot of black students going to open-access institutions. We have to address enrollment stratification.”

Black students disproportionately enroll at institutions that are open access and, therefore, tend to have lower graduation rates. One-quarter of black freshmen enroll at highly selective institutions -- those in the top quartile of institutions, based on SAT scores -- while 40 percent of white freshmen enroll at such a college.

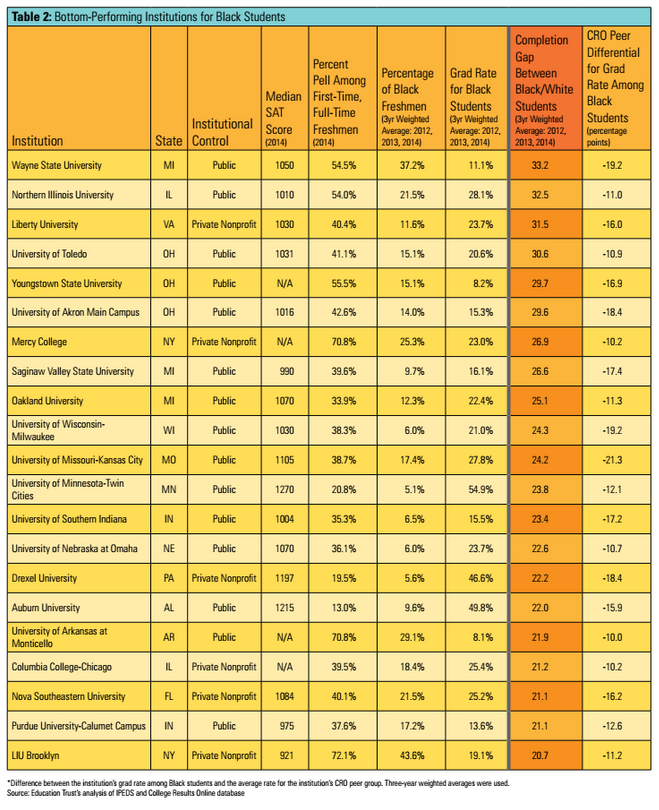

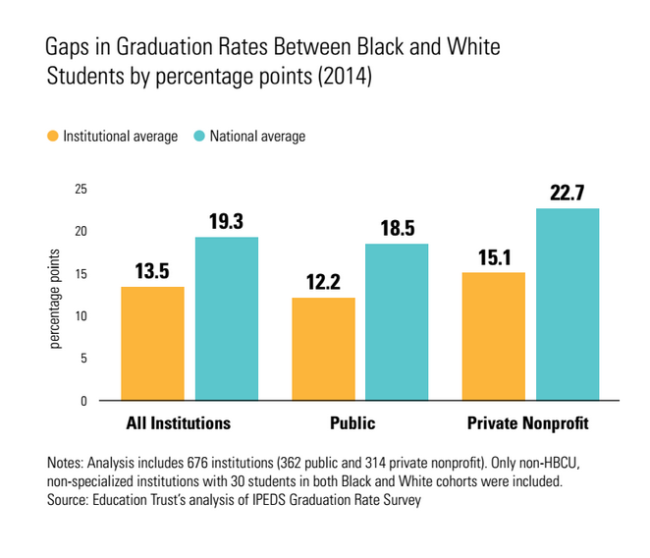

Nichols and his co-author, Denzel Evans-Bill, examined graduation data -- pulled from the U.S. Department of Education's Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System -- at all nonspecialized public and private nonprofit institutions, as well as four-year for-profit institutions, for first-time, full-time students who enrolled in 2008. They found that, nationally, graduation rates of black students lag behind those of white students by 22 percentage points. When the data were isolated to include only the 676 public and private nonprofit institutions, the gap was slightly smaller: black students graduated at a rate 19.3 percentage points lower than the 64.7 percent graduation rate for white students.

Among students who attended the same institutions, however, the average gap between white and black students is just 13.5 percentage points.

“If the graduation rate for black students were equal to the current graduation rate for white students at each institution where a gap exists, the national graduation rate for black students would still lag behind the national rate for white students,” the researchers wrote. “Eliminating institutional gaps at each campus in our sample would produce an additional 11,992 black graduates, and would reduce the national gap in black and white completion from 19.3 percentage points to 6.6 percentage points. These remaining 6.6 percentage points are the result of divergent enrollment patterns between black and white students.”

Closing the completion gap “requires simultaneous work on three fronts,” the report states: improving overall graduation rates at institutions where black students are most likely to attend, changing enrollment patterns so that selective institutions enroll more black students, and addressing whatever inequities are leading to completion gaps on individual campuses.

The report highlights some institutions that appear to be closing such gaps. More than 20 percent of colleges and universities have completion gaps that are at or below five percentage points. Among those institutions, 55 have either no gap at all or the gap is inverted.

Georgia State, Francis Marion and Winthrop Universities; the City University of New York’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice; the Universities of North Carolina at Greensboro, South Florida and South Carolina at Aiken; the State University of New York at Albany; the University of California, Riverside; and Keiser University, in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., all graduate black students at rates higher than white students.

“Through our analysis, we were able to find a handful of top-performing schools that we felt are really serving black students well and deserve to be recognized for that,” Nichols said. “On the other hand, we did also want to identify a number of schools that aren’t serving black students really well. These are schools that have significant gaps.”

That list includes Northern Illinois University, where just 28 percent of black students who enrolled in 2008 graduated within six years. White students graduated at a rate 32.5 percentage points higher. It also includes Liberty University, where only 23.7 percent of black students graduated -- a rate 31.5 percentage points lower than that of white students.

Liberty University did not respond to requests for comment. A spokesman for Northern Illinois University declined to comment.

Closing out the bottom three was Wayne State University, where only 11 percent of black students graduated in six years. That’s 33.2 percentage points lower than Wayne State’s white students. Nearly 40 percent of its first-time freshmen were black.

Monica Brockmeyer, Wayne State’s associate provost for student success, said the university has been working to close this gap and noted that it has improved graduation rates for black students since 2014, the last year included in the report.

Over the past five years, Brockmeyer said, Wayne State has invested more than $10 million in student success initiatives, including programs aimed at improving the completion rates of black students. That money has been used to hire more academic advisers, launch an Office of Multicultural Engagement and create a bridge program for incoming freshmen. The graduation rate for black students has risen from 11.1 percent in 2014 to 17 percent.

“That’s still too low,” Brockmeyer said. “But we do feel like this is the beginning of some positive gains. We really consider black students as core to our mission, so we have been aware and have been working on this issue.”

(Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly described the percentage of black and white freshmen who enroll at highly selective institutions. The story has been updated.)