You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

When it comes to shared governance, is OK good enough? That’s the question behind -- and the title of -- a new report from the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges. It’s based in part on input from a focus group of faculty members, conducted earlier this year in conjunction with the American Association of University Professors. Three hundred presidents and several thousand board members weighed in via surveys; their feedback makes up the bulk of the report.

The answer to the shared governance question? Not quite. While most presidents and board members from both public and private institutions believe that shared governance is working adequately, they believe it could be more effective. Some 95 percent of board members said that shared governance is a very important or moderately important component of decision making on their campuses, and they also overwhelmingly said that it’s important or moderately important to higher education overall.

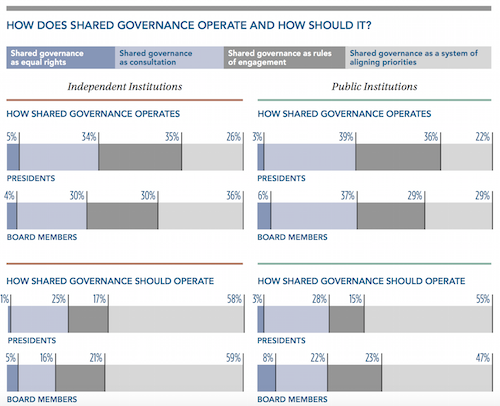

At the same time, very few presidents or board members see shared governance as sharing “equal rights” with other constituencies, including faculty members. The majority of respondents said it should work as a system of aligning priorities.

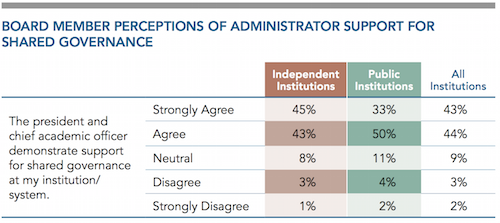

More than 80 percent of trustee and president respondents said they support faculty members’ role in overseeing academic programs. A smaller percentage, but still a significant majority, said that faculty members respect their role in overseeing their institutions. Interestingly, board members had a less positive view of administrative support for their authority.

“If it ever worked easily in the past (and such an assumption is speculative), in today’s environment, shared governance requires renewed effort to function well,” reads the report. “Governing boards and presidents report strong interest in developing high-functioning shared governance,” which “should be an essential institutional asset.”

Yet “careful board, president and faculty leadership is needed to prevent it from becoming a liability,” the report says.

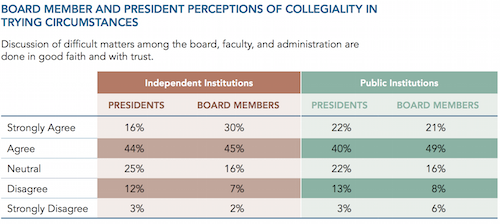

The majority of presidents and board members also reported that discussions of difficult matters among the board, faculty and administration are conducted in good faith, with trust.

At the same time, the survey also made clear that presidents think board and faculty members would benefit from better understanding each other’s roles. Only about 30 percent of presidents reported that the typical board member understands the work of the faculty well or very well, and only about 20 percent said that the typical faculty member understands the work of the board well or very well.

“That is, presidents perceived board members to have greater awareness of faculty responsibilities than the reverse, although in neither case was the answer impressive,” the report says. “Perhaps more remarkable is the tepid degree to which presidents believed members of either group typically understand the work of the other.”

One major area of concern is how the changing faculty role -- namely the decline of full-time, tenure-line positions -- is affecting shared governance. Some 50 percent of presidents at both public and private institutions said their policies related to shared governance haven’t changed, despite the dramatic shift toward part-time, non-tenure-track instructors, who historically have been shut out of institutional decision making.

Improving shared governance is major focus for AGB at the moment; it’s working on a white paper on the topic and has commissioned a book. Calling the matter “puzzling” in light of the changing faculty role, Susan Whealler Johnston, AGB’s executive vice president and CEO, said, “We know it’s particularly important to have effective shared governance, but we’re not sure how effective it is right now.”

Whether shared governance is OK or really bad -- as several recent, faculty-driven books claim -- probably depends on one’s perspective, Johnston said. “If you’re part of the growing percentage of part-time faculty and adjunct and contingent faculty and you’re excluded, it can look like a big failure. And if you’re part of the declining percentage of tenure-track faculty and you’re reeling from the pressure of taking on the burden of full shared governance, then it can also look like a failure.”

Shared governance is also a focus of the AAUP -- so much so that’s it’s holding a special conference on the topic, starting this week. AGB’s report will be discussed. Hans-Joerg Tiede, associate secretary for tenure, academic freedom and shared governance for AAUP, said the association wants to generate broad discussion about shared governance, on topics from presidential searches to the relationship between shared governance and collective bargaining.

AGB’s report closes with several questions for presidents and boards to consider. Have they received sufficient information about the nature of faculty work and the faculty role in shared governance, and do faculty members understand the board’s role, it asks. How well do board members understand the value that faculty members bring to institutional decision making? How might the institution benefit from more robust collaboration among governing boards, administration and faculty?