You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Georgia Budget & Policy Institute

Then Governor Zell Miller deployed soaring rhetoric in 1992 when he called for a new state lottery-funded scholarship program in Georgia.

“With the lottery proceeds, Georgia can provide scholarships by the thousands to deserving students who want to go to college or a vocational school,” Miller said that year in his State of the State address. “This is Georgia’s opportunity to pioneer the most far-reaching scholarship program in the nation -- and not only for those who are minorities or who come from lower-income families, but also those middle-income families who are devastated with the cost of education and training beyond high school.”

Georgia would go on to establish the Helping Outstanding Pupils Educationally, or HOPE, financial assistance program. The state made the first HOPE awards in the 1993-94 academic year. Since then, HOPE, which includes several different scholarships and grants, has come to be viewed as a trendsetting program providing non-need-based aid, also called merit aid, to top-achieving Georgia students who stay in the state for higher education. From HOPE's inception, the state's top colleges -- such as Georgia Tech and the University of Georgia -- have credited it with attracting top students who in the past might well have gone out of state.

HOPE assistance has gone to more than 1.75 million students and totaled more than $7 billion, according to the Georgia Student Finance Commission. The program has been credited with sparking non-need-based-aid programs in many other states.

But a new report out last week argues that HOPE is missing many students with its focus on high achievers. Students from low-income families and minority students are less likely to receive HOPE assistance, the report said. It goes on to argue that recent cuts to the program have hurt its ability to help some students pay for college.

The report, which analyzed 2013 data, concludes by arguing Georgia needs to start a new need-based-aid program and expand other aspects of the HOPE program. It comes at an important time in Georgia, where lawmakers have debated expanding gambling, which could fund scholarships, and in recent years have significantly changed the HOPE program as costs outpaced lottery revenues.

But the report, released Sept. 8 by the Georgia Budget & Policy Institute, also reflects a policy discussion likely to sweep many states in the coming years, experts said. States will have to grapple with the question of how they continue to pay for non-need-based-aid programs for top students while finding ways to expand access for students who haven’t traditionally earned degrees or diplomas.

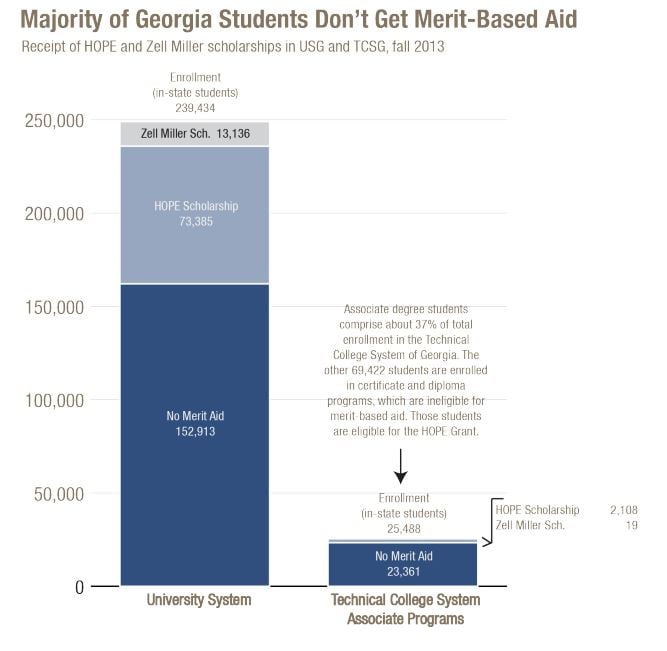

A main finding of the report is that fewer than half of Georgia’s in-state students benefit from its flagship merit-based-aid programs, the HOPE Scholarship and the Zell Miller Scholarship. The HOPE Scholarship is available to Georgia residents graduating from high school with a 3.0 grade point average and attending in-state institutions. Scholarship amounts fluctuate with tuition and lottery revenue levels but averaged 84 percent of tuition at university system institutions in 2015-16. The Zell Miller Scholarship, created in 2011, is essentially a higher tier of the HOPE scholarship. It has more stringent eligibility requirements -- a 3.7 high school grade point average and high standardized test scores -- but it covers full tuition in Georgia. Although both the HOPE and Zell Miller scholarships have a number of additional requirements including academic progress, they do not list income limits or requirements.

The HOPE and Zell Miller Scholarships only reach about 36 percent of students in Georgia’s university system, the report found -- just under 31 percent of students received HOPE Scholarships and 5.5 percent received Zell Miller Scholarships. That left 64 percent of the state’s 239,434 in-state university system undergraduates receiving no non-need-based aid from the state as of the fall of 2013.

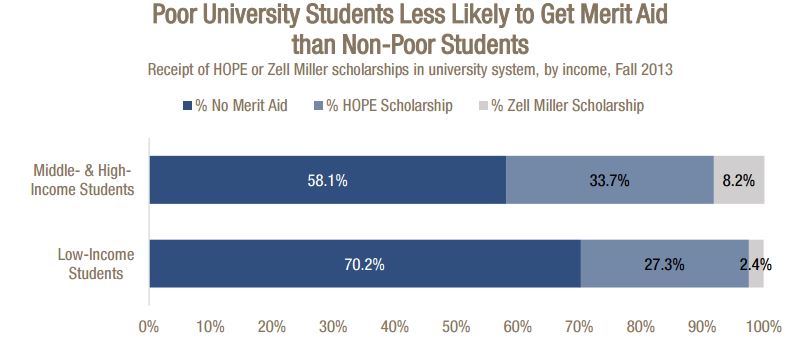

The report also found the scholarships skew away from low-income students. About 30 percent of low-income students in the university system received the HOPE or Zell Miller scholarships. Almost 42 percent of middle-income and high-income students received the scholarships.

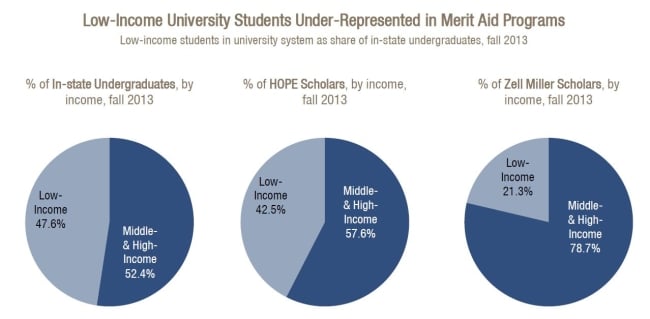

The point is also demonstrated another way, by comparing an income breakdown of students receiving scholarships to that of the entire student population (as demonstrated in the graphic at the top of this story). Low-income students were 47.6 percent of in-state university system undergraduates in the fall of 2013. But they were just 42.5 percent of HOPE scholarship recipients and 21.3 percent of Zell Miller Scholarship recipients.

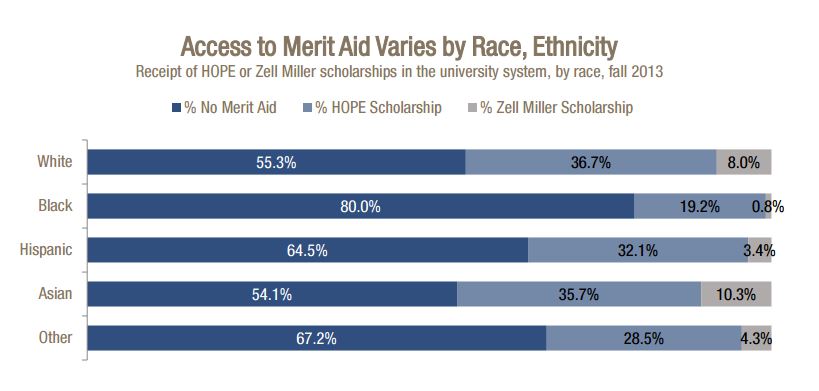

Further, students from historically marginalized groups are less likely to receive the non-need-based scholarships, the report found. Just 20 percent of black students and less than 36 percent of Hispanic students within the university system received either the HOPE or Zell Miller scholarships. That compares to 46 percent of Asian-American students and nearly 45 percent of white students.

The findings come as low-income students have increased in number in Georgia’s university system. The report said that in the fall of 2006, about 27 percent of undergraduate students in the system received Pell Grants, which are typically considered a proxy for poverty. By 2014, the portion of Pell Grant recipients rose to 44.5 percent.

Rising numbers of low-income students are connected to increases in enrollment of minority students, who experience higher poverty rates, the report said.

“The students who have the least in financial resources are least likely to actually participate in the programs,” said Claire Suggs, senior education policy analyst at the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank, and the report’s author. “That certainly has implications about, even, whether or not students would pursue a postsecondary degree.”

The university system dropped 6,500 students in the fall of 2014 for not paying tuition and fees, the report said.

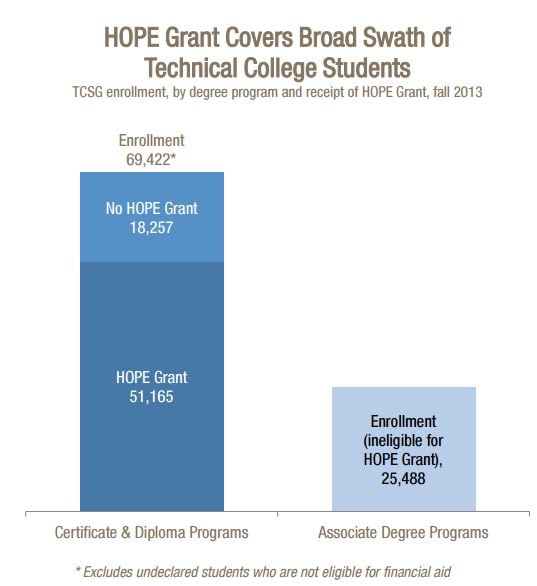

The report finds that another HOPE program, the HOPE Grant, more effectively reaches low-income and minority students. The HOPE Grant is for Georgia residents enrolling in certificate or diploma programs, often in technical colleges. It covers roughly three-quarters of tuition in the technical college system, the report said.

HOPE Grants reached about 74 percent of 69,422 eligible technical college students in certificate or diploma programs, the report found. They reached 85 percent of low-income students, 75 percent of white students, 73 percent of black students, 70 percent of Hispanic students and 54 percent of Asian students.

But the report pointed to issues surrounding the HOPE Grant as well. It no longer meets students’ full financial need after changes put in place in 2011, and funding for mandatory fees and book allowances was eliminated that year as well, Suggs said. Some of those changes were also put in place for the HOPE Scholarship.

But the changes are particularly pertinent for the HOPE Grant, given the current high profile of tuition-free community college programs like the Tennessee Promise.

“For almost 20 years in Georgia, you couldn’t get a degree, but you could go through and get a certificate or a diploma, essentially for free with tuition or mandatory fees being covered,” Suggs said. “That’s no longer the case.”

The report concludes that the HOPE Grant should be restored to cover full tuition plus fees for technical college. It also makes a recommendation for the HOPE Scholarship -- eliminate a rule preventing most students who have been out of high school for more than seven years from receiving the scholarship. That rule does not serve adult students who are increasingly enrolling in postsecondary programs, it said.

Perhaps the report’s biggest recommendation, however, is that Georgia create a new stand-alone need-based-aid program. The program wouldn’t replace the HOPE Scholarship’s non-need-based aid, Suggs said.

“That’s one thing that Georgia does not have, a need-based program for students seeking degrees,” she said. “Whether it’s the associate or bachelor’s degree, if you don’t get the HOPE, if you don’t qualify, there really isn’t any other source of state aid you can turn to.”

Such a program could come with a large price tag. Students’ unmet need totaled $660 million across the university system in 2013-14, the report said. The system raised a comparatively small $28.8 million for need-based aid.

While the report does not wade into many specifics on a potential need-based-aid program or how to pay for it, Suggs said legislators could consider several options. The Georgia Budget and Policy Institute has in the past pointed to possibilities from closing tax loopholes, increasing cigarette taxes and more comprehensive tax reform packages. There is also the potential for revenue from casino gaming.

Ultimately, the need is clear, Suggs said. It could be politically palatable, because Georgia needs educated workers, she said.

“I think this is starting to bubble up, and I think there is growing awareness that there are many students who are struggling to cover their cost of college,” Suggs said. “And there is definitely awareness of workforce needs.”

Questions of budgets and aid programs have already come in up in other states. Take Louisiana, which earlier this year decided to stop funding for its merit-based scholarship program amid a budget deficit. Such issues and others raised in the Georgia report will likely come up in other states in the future, experts said.

“These are issues in many states, because quite a few states have copied Georgia’s model for merit aid,” said Robert Kelchen, an assistant professor of higher education at Seton Hall University whose specialties include student aid. “Georgia is one of the states that have scaled back the generosity of merit aid in recent years. To come up with additional money for need-based aid would be difficult, but getting rid of the politically popular merit-based program would be exceedingly difficult.”

Kelchen said the report’s mention of adult students was important because that group is left out of many policies and proposals, including Tennessee’s tuition-free community college program. He was not surprised, however, that the non-need-based aid tended to go toward higher-income students in Georgia.

“The goal of the merit program is to keep top students in the state,” Kelchen said. “These programs have been pretty effective at doing that. They’re not great at increasing overall higher ed attainment.”

The report’s findings point to higher education having to educate more students more efficiently than it has in the past, said George Pernsteiner, president of the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association. The growing question is whether Georgia’s non-need-based-aid programs and others it inspired fit the needs of states and students today. That includes students from backgrounds who may not have enrolled in high numbers in the past.

“It may be time in many of the states to take a look at what we are now trying to achieve with our higher education systems,” Pernsteiner said. “States now have to be concerned about -- and almost all states are concerned about -- the educational attainment level of their entire adult population.”

In some ways, this is the next step in an evolving conversation, Pernsteiner said. Early in the 1990s, states like Georgia focused on getting students to go to college and stay in state. Then the conversation was about who should pay. Today, the conversation has shifted to what should be paid for by states.

“What we learned in Georgia and what we learned in Louisiana is the demands on merit systems like the Georgia HOPE program far outstrips the availability of the revenue sources we’ve created to meet that demand,” Pernsteiner said. “At the same time, you’ve got folks saying we’ve got to expand who aid is used for.”