You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The key to graduating in four years (at least in the minds of many parents) is picking a major early and sticking with it. But a new report suggests students who change their major as late as senior year are more likely to graduate from college than students who settle on one the second they set foot on campus.

The report, published by the Education Advisory Board, a research and consulting firm based in Washington, D.C., challenges the notion that changing majors is keeping students in college past their intended graduation date and driving up their debt. Instead of looking at when students first declared a major, the EAB's study explored the connection between students' final declaration and how it affected their time to degree and graduation rates.

“Maybe the first-choice question is a red herring?” said Ed Venit, a senior director at the EAB. “Maybe the most important decision is the final major you choose?”

Most students -- as many as 80 percent in some surveys -- will switch majors at one point during their time in college. According to the report, students who made a final decision as late as the fifth term they were enrolled did not see their time to graduation increase. Even one-quarter of the students who landed on a final major during senior year graduated in four years, the EAB found.

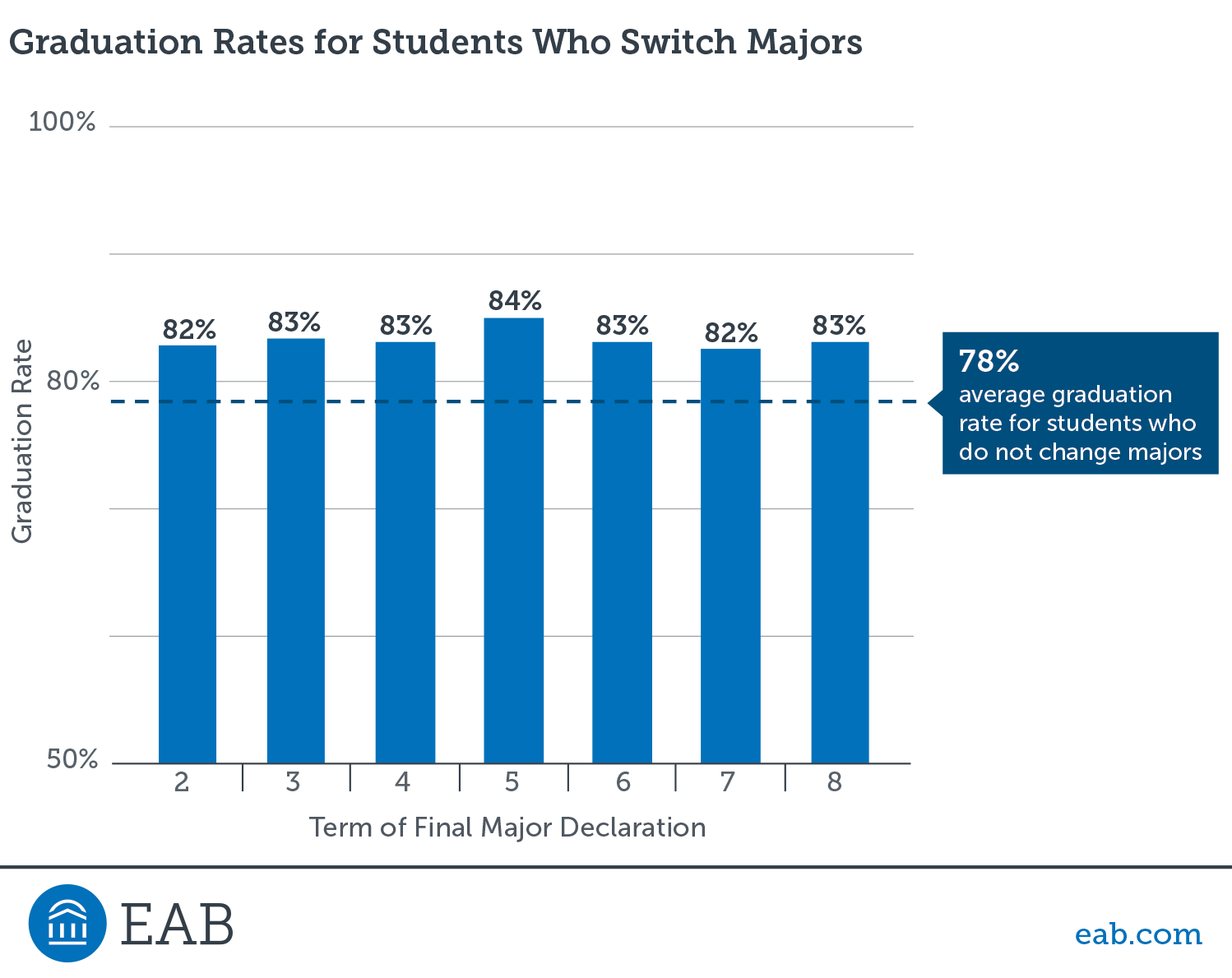

Neither did settling on a final major during the second through eighth terms of enrollment influence students’ graduation rates. Students who declared a new major during any of those terms posted a graduation rate of between 82 and 84 percent.

The EAB used data provided by colleges in its Student Success Collaborative for the study. The collaborative is a membership organization for colleges and universities that uses data-assisted research to improve student support, retention and graduation rates.

Ten member institutions of the collaborative supplied at least six years’ worth of data about more than 78,000 students who either graduated or left the institution for the study. The colleges were not named, but the EAB said they were selected to “provide a representative snapshot of national major declaration trends.” The sample included both public and private institutions -- all of them on the semester calendar -- with enrollments ranging from 5,800 to more than 42,000.

The study looked only at students who had accrued 60 or more credits to avoid including students who dropped out as freshmen or sophomores in the final data. It also focused on when students settled on a final major, ignoring any other times they may have switched.

Most colleges have policies in place governing when students need to declare a major, but few have firm policies saying how many times a student can switch. The data suggest switching majors can be a positive experience for students, as opposed to an acknowledgment that they initially made the wrong decision.

For example, students who never switched majors had a slightly lower graduation rate than did students who made a switch. While graduation rates hovered around 83 percent for students who finalized their major during their second semester or later, students who declared a major during their first semester in college and stuck with it were four percentage points less likely to graduate.

The EAB did not explore the reasons behind that gap in this study, but Venit speculated it could have something to do with students who enroll in preprofessional programs -- law, medicine, nursing and so on -- but aren’t admitted and drop out as a result.

Alternatively, Venit said, some students who declare a major as freshmen may feel obligated to do so -- perhaps because of pressure from family members -- and end up not graduating.

“They’re pursuing it, and they don’t necessarily feel that they’re in love with it, but they’re also not sure if they can leave it,” Venit said. “They’re just making a choice to continue on.”

Students who change their majors, meanwhile, may be responding to their own changing interests and maturation as they move from being teenagers to young adults. Like transfer students, who make a decision to move from one college to another, “the act of major switching itself is a positive indicator of engagement,” Venit said.

Other than a reminder that “policies that encourage or force students to make choices early on in their careers may not be doing much to help students,” the report doesn’t make any policy recommendations to colleges. Venit said colleges should continue to allow students to switch majors and instead focus on encouraging the act of exploration in the first place.

Georgia State University is one institution that does that. The university is one of several that offers “metamajors,” clusters of courses in the same general field -- business, humanities or STEM, for example -- that let undeclared students discover areas of interest while at the same time giving them a somewhat structured pathway toward graduation.

The university, which enrolls mostly first-generation students from low-income backgrounds, used to require students to pick one of its roughly 90 majors as freshmen. About six years ago, the university realized students went through about 2.5 majors before they graduated.

“We were not doing a good job of fitting students into the right major,” said Timothy M. Renick, vice provost and vice president for enrollment management and student success. “It was overwhelming, especially for first-generation, low-income students … to try to wade through these choices and options. In most cases students were making the wrong choices.”

Now, students choose from one of seven metamajors. A student who wishes to become an accountant, for example, enrolls in the business metamajor, and every course that student takes in that metamajor applies toward graduation. If, down the line, the student decides to switch from accounting to management, previously earned credits still count toward that degree, Renick said.

After enrolling in the metamajor (which for some students lasts for one semester; for others, two semesters plus the preceding summer term), students then go on to select majors. At that point, “Most freshmen are prepared to make a much more informed decision,” Renick said, though they are still free to delay that decision if they remain undecided.

Georgia State has offered metamajors for the past three academic years. During that time, the university has seen a 32 percent drop in the number of major changes among its undergraduates, Renick said. Additionally, students who graduated this spring took on average about half a semester less time to finish their degree requirements than students in the class of 2013, he said.

“There’s no value to try to force a student’s hand as they enter the university,” Renick said. “An ill-informed choice is worse than no choice at all.”