You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

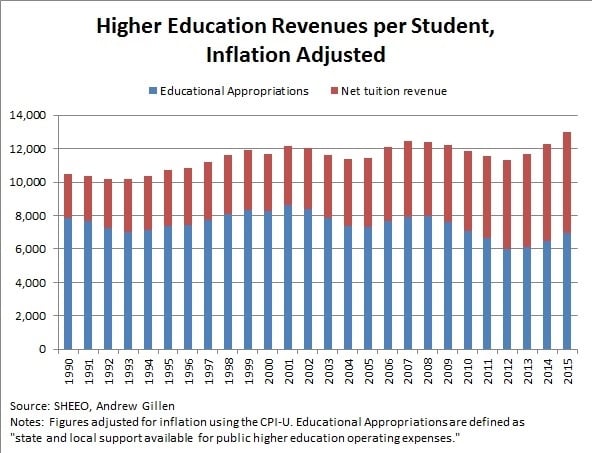

Andrew Gillen argues state funding for higher education is cyclical and that total revenue has been trending up over time.

Andrew Gillen

Critics are launching another salvo in a long-simmering debate over the underlying math used to gauge changes in higher education finances over time, arguing a cost-adjustment index used in a closely watched report obscures true trends in revenue.

At issue is the Higher Education Cost Adjustment, an inflationary index developed by the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association and used in its annual State Higher Education Finance report. The index was designed to estimate inflation in the costs that colleges and universities pay. But its critics say that by focusing on what institutions spend, rather than on what students pay, the adjustment is out of step with the rising costs students face -- and actually hides a slight upward trend in revenue per student at colleges and universities.

The use of HECA has implications beyond numbers on a page, those critics say. Misreading revenue trends can have real effects on the policy choices made around state funding and tuition rates, leading decision makers to push the wrong levers when attempting to keep cost of attendance affordable. Others have argued that the cost index contributes to a feedback loop in which perceived higher costs prompt legislators to give colleges and universities more funds than are needed, which in turn allows the institutions to spend -- and charge -- more.

But HECA’s defenders respond that the index is a tool like any other, one creating data for a specific context. A key part of their defense is that HECA is intended to show the financial pressures universities face, which by nature are different from those students at public colleges and universities experience. Further, they say HECA is not particularly out of step with the most widely known consumer inflationary measure, the Consumer Price Index.

In some ways, the two sides are talking past one another as they focus on different sides of the higher education financial equation. In other ways, the debate shows just how opaque and complex the relationship can be between higher education costs and tuition -- every expert seems to have their own take on the most important underlying factors.

What Is the Higher Education Cost Adjustment?

SHEEO developed HECA as an alternative to two other inflationary measures, CPI and the Higher Education Price Index. It was intended to account for differences in the costs colleges face and the consumer-oriented costs accounted for in CPI. At the same time, HECA tried to account for some criticisms lobbed at HEPI, which had drawn fire for being privately developed, being self-referential because it relied heavily on average faculty salaries and being potentially costly to update and maintain.

Underpinning HECA are indexes developed and updated by the federal government. It’s tilted heavily toward personnel costs under the reasoning that faculty and staff costs are the largest portion of higher education institutions’ expenditures. A full 75 percent of HECA is the Employment Cost Index -- personnel costs -- and 25 percent is the Gross Domestic Product Implicit Price Deflator -- nonpersonnel costs. But HECA has also been criticized as being self-referential. It should not be used as a basis for increasing state funding, an argument goes, because it exaggerates what colleges and universities have to spend, making it more likely that state funding will appear to be falling behind costs.

The man leading the latest charge against HECA is Andrew Gillen, an independent higher education analyst and longtime critic of the cost adjustment. His basic argument starts with the idea that using HECA makes it harder to see a slight upward trend over time in institutions’ revenue per student -- revenue from state and local appropriations combined with net tuition revenue. Adjusting using CPI shows that revenue per student reached an all-time high of $12,972 in the 2015 fiscal year, he said, surpassing a previous high of $12,440 in 2007. That’s a larger margin than you get when adjusting for HECA, which shows revenue rising to $12,972 in 2015, up from $12,723 in 2007.

.jpg)

The all-time high came as state funding for higher education recovered somewhat from the recession, Gillen said. He rejected the idea that state funding per student is in long-term decline. His data show state appropriations per student lower in 2015 than they were before the recession but still increasing in recent years, keeping with a cyclical pattern that's established itself over previous economic cycles.

Further, tuition does not change in lockstep with state funding, Gillen said. He performed an analysis without HECA showing that every one-dollar decrease in state funding is only correlated with a seven-cent increase in tuition. If tuition were perfectly linked to state funding, the two indicators should change in a one-to-one ratio, he said.

Misreading the trends in revenue because of cost adjustments will lead to misdiagnosing the way costs are changing over time -- and misdiagnosing, in turn, the reasons tuition has been increasing, Gillen said. The common narrative is that declines in state funding have led to higher tuition, he said. But because his analysis shows state funding has cycled over time while revenue has crept up and tuition steadily increased, Gillen believes there has been too much emphasis on state funding. Increasing state funding is actually more likely to feed the trend of higher costs and tuition, he said.

So other elements of higher education finance need to be considered, Gillen said.

“That’s really why I keep writing,” he said. “If I’m wrong, then the way to keep tuition low is to keep increasing state funding. But if I’m right and you keep increasing state funding, that’s not going to do anything to tuition. Tuition is going to keep going up.”

Colleges and universities will raise all the money they can, and they will spend all the money they raise, Gillen said. Under his logic, an increase in state funding does nothing but increase the cap on what institutions can raise and spend.

Following Gillen’s reasoning can lead to very different ideas for keeping tuition in check. He suggested finding ways to change the incentives colleges and universities face.

“There are two ways you can escape this problem of just feeding the trend,” Gillen said. “Getting higher education to stop competing based on reputation -- compete based on value. Or cap revenue and start taking that away as colleges reach whatever is determined to be an adequate level.”

But many see the debate over cost indexes as a distraction from evaluating the trends in finance.

“This HECA versus CPI debate is a red herring, to be blunt,” said Andy Carlson, a senior policy analyst at the State Higher Education Executive Officers association. “CPI versus HECA is just a nitpicky argument that distracts.”

The two indexes have been tracking closely, and SHEEO discusses them in its report materials to provide transparency, Carlson said. CPI went up by 8.4 percent over the five years ending in 2015, according to SHEEO. By comparison, HECA increased by 9.8 percent.

Further, SHEEO created its report to look at finances from the educational provider perspective, Carlson said. HECA adjusts for the fact that most higher education costs are driven by salaries and benefits. Only a quarter of HECA is based on the cost of goods, and three-quarters is based on salaries for white-collar professionals. That’s very different than CPI, designed to measure goods and services consumers purchase.

“From my perspective, HECA makes perfect sense if you really want to focus on the revenue,” Carlson said. “But if you really want to focus on tuitions and students and families, CPI is really a much more valuable measure.”

“For every person who says we shouldn’t use HECA, we’ve got somebody else who sharply depends on it,” Carlson said. “An analyst can do both. They can pick the one that works best for them.”

No inflationary measure is going to be perfect. Some might argue HECA is out of step with consumers, but university business officers could also claim it doesn’t recognize some of the newest costs they face. It does not account for pensions or insurance cost increases, which are expenses institutions increasingly take on as they’re shifted over from states, Carlson said.

He thinks some trends are apparent regardless of the index used.

“Whether you use CPI or HECA, it’s clear on the state and local funding side that funding hasn’t kept up with enrollment growth and with inflation,” Carlson said, an opinion contrasting with Gillen’s assertion that state funding is cyclical. “The reality is the share coming from tuition has increased significantly.”

SHEEO experts haven’t been the only ones to pick out trends regardless of inflationary measure.

Susan Dynarski is a professor of public policy, education and economics at the University of Michigan who studies the issue of college costs. In doing so, she wrote about CPI and HECA in October 2014. She found that under CPI, a consumer needed $1.97 in 2013 to buy what would have cost $1 in 1988. Under HECA, the split is $2.12 versus $1.

While that is a difference, it is also spread out over 25 years.

“It seemed like, most of the time, these things tracked together,” Dynarski said.

Still, some say a special cost index for higher education sets up a feedback loop constantly pushing both prices and expenses upward.

“It’s like a crutch,” said Art Hauptman, an independent public policy consultant specializing in higher education finance. “It’s a self-sustaining prophecy. Higher education prices go up faster, and therefore costs go up faster, and therefore the price index is higher.”

Hauptman falls more in line with Gillen in the discussion over indexes and costs. One of his ideas is to stop focusing on what public institutions actually spend and focus more on what they should be spending. Set a realistic funding level per student in a given field, and allow institutions to decide how to best educate with it. He views higher education as roughly analogous to the health care industry -- growth in health care costs only slowed when the money dried up, he said.

“Do you think costs are driving the prices or do you think prices are driving the costs?” he said. “If you think the underlying costs are driving the price, you sort of get into this argument. I don’t believe it.”

The index debate doesn’t seem to have translated into discussions within college and university business offices, however. It’s largely an academic argument, said Donald Heller, provost and vice president of academic affairs at the University of San Francisco.

Heller said he’s not aware of any university that sets its tuition based on cost indexes -- nor is he aware of the indexes playing a key role in state appropriation deliberations. He did not sound surprised, however, that the index issue was sparking more debate.

“Every now and then it pops up,” he said. “Generally, you have people in higher ed saying we need to use something other than the CPI because the CPI doesn’t really reflect our cost structure, things we spend money on. And then people on the other side of the debate say CPI makes more sense because when people go to pay for higher education, their lives are dictated by what they face when they have to buy things.”