You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

James Finkelstein

When public college or university presidents are hired, their salaries always attract attention. But new research suggests the real growth in executive costs may be due to expenses and benefits, which these days go beyond the charge to live in the president's mansion.

Presidents’ contracts have become long, complex and stuffed with extra benefits going far beyond base salary and a place to live, according to new research from James Finkelstein, a public policy professor at George Mason University who has been analyzing presidential contracts for several years. Finkelstein is scheduled to share his findings at the American Association of University Professors’ annual conference Thursday in Washington.

He is using his work to call for more transparency in presidential contracts at public universities, like posting them online. But some say that could bring about unintended consequences and argue contracts and the benefits in them are dictated by the marketplace.

Finkelstein's presentation is titled “The Corporatization of Presidential Contracts,” and it sums up a review of 115 presidential contracts at state-funded institutions of higher education around the country. In short, contracts for higher education leaders are increasingly looking like employment agreements for chief executive officers at corporations, Finkelstein said. That’s happening as more and more business executives and CEOs become college and university trustees.

“In the last 20, 30 years, the notion of what the employment agreements and compensation for university presidents looks like has changed,” Finkelstein said. “We think of them more like CEOs than public executives. But they are public officials, and we treat them differently from any other class of public officials in our society.”

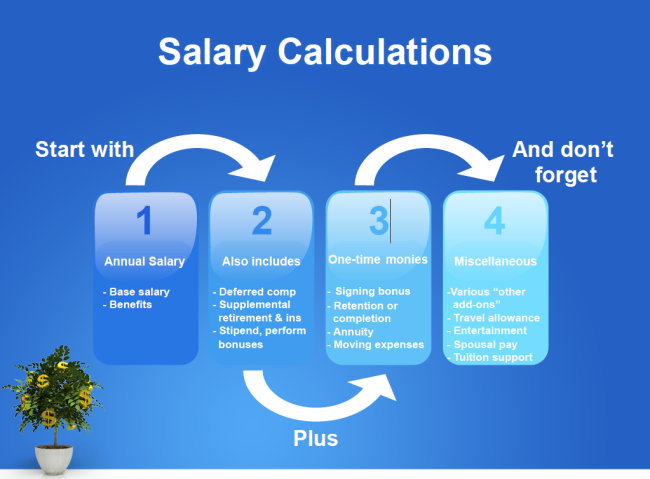

The changes to contract structures mean base salaries don’t come close to reflecting contracts’ actual values. Base salaries for presidents averaged $437,347, according to Finkelstein’s work. They ranged from a low of $136,200 to $900,000.

But one-time payments -- perks like retention bonuses, signing bonuses and moving reimbursements -- averaged $145,400. They ranged in value from $900 to $1 million.

Including base salary and other forms of compensation, total compensation averaged $605,396. Total compensation ranged from $250,000 to $1.3 million.

“Most astounding to me were the number of bonuses, the types of bonuses, the extra things,” said Judith A. Wilde, the chief operating officer at the School of Policy, Government and International Affairs at George Mason University, who is researching on Finkelstein’s project and performing data analysis. “When you read about salary, you expect it to be about salary.”

Perks and benefits packed into contracts ranged from those that might be expected to some that are more unique. Most contracts, 88 percent, included provisions providing standard benefits like health coverage. Additional benefits like supplemental life insurance, supplemental disability insurance and annual physical examinations were written into 58 percent of contracts.

Nearly three-quarters of contracts, 72 percent, required living in university housing -- a president’s residence. About a fifth, 17 percent, called for a housing allowance. That allowance averaged $42,533 a year, with specific values ranging from $18,000 to $72,000.

Unique perks included prenegotiated seating at athletic events, even after presidents resign. One contract called for courtside seats at volleyball games, Finkelstein said. Other perks he noted included reimbursements for home offices, car allowances of up to $18,000 per year and reimbursements for internet connectivity. Finkelstein did not name specific universities or presidents in his research.

Many contracts also provided for presidents after they left the top spot. Faculty appointments were written into 72 percent of contracts. Of those, 95 percent called for tenure and 5 percent called for term appointments. Salaries in postpresidential appointments were based on different factors, with 26 percent of contracts calling for salaries to be based on a percentage of presidential salary, 34 percent calling for it to be relative to highest-paid faculty salary and 3 percent saying it would be an average of full professors' salaries.

Those postpresidential appointments have real costs, said Finkelstein. He did not provide names for any specific contracts but said one president was guaranteed a faculty role at 75 percent of his presidential salary after he stepped down from the top job.

“We figured he could work as many as 10 years after he stepped down, one of which would be sabbatical,” Finkelstein said. “The postpresidential liability for that institution is over $4 million over those 10 years, to teach two courses a year.”

Contracts varied widely on whether they allowed presidents to work outside of their institutions in roles like directors on boards, consultants or speakers. Outside work was allowed for 66 percent of presidents. Working for a for-profit was allowed for half of presidents, consulting was allowed for 10 percent, speaking was permitted for 8 percent and writing was allowed for 7 percent.

That’s notable in a conversation about presidential compensation, because leaders can earn hundreds of thousands of dollars working for other organizations. Finkelstein pointed to a 2010 study he performed finding 33 percent of university presidents served on boards for publicly traded companies at an average pay of $148,000 per year per board. That study found 43 presidents earned nearly $11 million in compensation from board service in one year.

The influx of corporate leaders on university boards isn’t the only possible factor behind the changes to presidential compensation, Finkelstein said. Presidents’ lawyers are likely pushing for more lucrative contracts, and presidents could be getting new ideas from other employment agreements. Finkelstein pointed out that presidents typically have to sign contracts for head football coaches, who often have perks like use of a private airplane, ostensibly for recruiting.

Finkelstein calls for publicly posting presidential contracts. His research required open records requests and dealing with numerous university offices or bodies. Some only provided parts of the information he requested. There are major roadblocks standing in the way of most members of the public reviewing university presidents’ contracts, he said.

Universities publicly posting presidential contracts would set up a situation similar to that for the country’s publicly traded companies, which have to submit documents detailing executive compensation to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. The SEC hosts those documents online.

Finkelstein wants contracts to be easily accessible because they deal with public officials who are among their states’ top-paid employees, he said. The contracts could also be important to wider discussions about university costs. Changes to presidential contracts could be setting the tone for increasing administrative expenses, Finkelstein said.

“Once you get a president who is very privileged, he or she tends to take that into the workplace,” Wilde said. “Part of the expenses you’re seeing growing at universities is administration as a whole, as the presidents feel they need more and more staff to support them.” (Note: This paragraph has been corrected to note Wilde was the speaker.)

Even the highest presidential compensation of $1.3 million would be a small line item in operating budgets at the largest public research universities, which can spend billions of dollars annually. But Finkelstein said it’s important to have a better view of compensation levels so changes can be discussed.

“I’m not taking a position for or against,” he said. “What I’m suggesting is that one of the things that a study like this highlights is the need to have a public discussion about whether or not this is how we want to treat the leaders of our public colleges and universities.”

Yet there are problems with the idea of posting contracts publicly, said Raymond D. Cotton, a Washington lawyer who specializes in representing both boards and presidents in contract negotiations. The lengthy and dense presidential contract documents can be difficult to interpret correctly, he said. Anyone looking at the contract from afar could also be glancing at someone’s pay stub without seeing the work they performed firsthand.

“The media loves to put up their articles on what the president is getting paid,” Cotton said. “What they don’t put up is the other side of the ledger. What is he or she doing for the money? That you rarely see.”

Cotton did agree that presidents’ contracts are looking more and more like those of corporate CEOs. And he agreed that the changes are being driven by business executives moving onto university boards. But compensation strategies aren’t the only thing bleeding over from the business world, he said.

Board members are increasingly becoming impatient with presidents, Cotton said. That can make it hard for presidents to get the time necessary to carry out their agendas. Take the case of University of Virginia President Teresa Sullivan, who was one of Cotton’s clients, he said.

Sullivan unexpectedly announced plans to leave the university in 2012, citing philosophical differences, only to be reinstated just two weeks later following an outcry. Many saw the incident as being driven by then Board of Visitors Rector Helen E. Dragas, a real estate developer.

“The values in the business world, the management values and techniques, some of them work and some of them don’t,” Cotton said. “It’s a mixed blessing.”

Some of the presidential perks aren’t all they are cracked up to be, either, according to Cotton. Take the president’s house. It’s a fishbowl on campus, allowing many to watch a president’s coming and going. It also doesn’t stay with a president after he or she leaves office, meaning they haven’t built any home equity. Presidential houses are also often used to host university-related events -- effectively turning a president’s home into a workplace.

Arguments can be made for other benefits packed into presidents’ contracts. Retention bonuses, for example, can be seen as “golden handcuffs” designed to keep talented leaders who prove they can raise money and boost a university’s profile.

Presidents are paid in accordance with the marketplace, Cotton said. While presidents want to earn what they can, boards are not inclined to pay more than they have to, he argued.

“I have never met, in all the work that I’ve done, a trustee who’s interested in wasting the money of the institution,” he said. “Quite the opposite, especially if they’re donors.”

Cotton also rejected the idea that a president with a lucrative contract must be bad for an institution’s bottom line.

“Quite honestly, that’s not happening,” he said. “I tell boards all the time that the most cost-effective investment they’ll make as a trustee is getting the best president they can get for their institution, because he or she will then go on to bring millions and millions of dollars in if they recruit effectively and surround themselves with talent.”