You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Scott Scarborough's two years as president at the University of Akron were controversial.

University of Akron

Scott L. Scarborough’s sudden departure from the University of Akron presidency Tuesday ended a short and tumultuous stint in which he found few friends on campus while trying to change the university’s direction, expand its reach and contain costs.

To faculty and other critics, Scarborough was someone who didn't understand the university's mission or respect academic values. And they said he spent plenty of money on questionable projects.

After being hired to take over at Akron in July of 2014, Scarborough absorbed intensifying criticism over the last year amid moves to rebrand Akron as a polytechnic institution and to lay off employees. His relationship with faculty members and students became increasingly strained amid perceptions of outsourcing and a preference for the private sector, ultimately culminating in a sweeping vote of no confidence from the Faculty Senate in February.

Meanwhile, plans to use discounted online-heavy classes to help Akron grow struggled to take hold. Other significant changes were reversed after they were announced. And a cloud of bad press seemed to follow Scarborough during his last year as president, particularly after the university spent $950,000 on renovations to the presidential home shortly after it announced it was laying off more than 200 employees.

Many faculty members believe Scarborough’s presidency became untenable after it emerged that Akron was in talks to partner with the embattled for-profit ITT Tech -- a deal that would have fit under a hub-and-spoke strategy the president touted to turn the university into a national institution using its Akron campus as a core. But the university is also facing a steep decline in enrollment for the fall semester that raises questions about its finances and footing for the future.

While any combination of factors might have led to Scarborough’s departure, the deciding point is not clear. Neither Akron’s Board of Trustees nor Scarborough gave a specific reason for his departure in statements released Tuesday. They only called the decision a mutual agreement.

“It is our belief that new leadership is needed for the university to move forward and achieve sustained success in the future,” Scarborough said in a three-paragraph letter addressed to faculty, staff and students. “As I look forward to the next chapter in my life, I hope that our faculty and staff, our passionate alumni, generous donors and committed and sincere members of the Akron community come together to advance the process of change and continuous improvement necessary for The University of Akron to realize its vast potential.”

Scarborough was hired to fix Akron’s finances, improve its enrollment and increase its educational quality, according to a statement from Jonathan T. Pavloff, the board chair.

"The board is grateful to him for his effort and recognizes that addressing those challenges required courage and the willingness to consider, and in some cases, implement needed changes in the way the university operates,” the board’s statement said. “The board is charged with ensuring the effective governance, leadership and management of the university and, along with Dr. Scarborough, determined that new leadership is needed for the University to move forward and achieve sustained success in the future.”

Akron did not make Scarborough available for comment and he did not immediately respond to individual requests for comment Tuesday. Pavloff said no single event led to the board making the change.

"It was the consistent review and analysis of how to best move forward that brought us to this consensus at this time,” Pavloff said, according to The Akron Beacon Journal. "We certainly considered the opinions of all the university’s constituents ... They are all important. They all need to be together working in concert for the university to succeed so we found that it’s best for new leadership to come into place to bring all the constituency groups to work together.”

What is clear is that enrollment dropped precariously during Scarborough’s second year as president. New freshman confirmations are down 23 percent year over year as of late May. That’s narrowed substantially from three months earlier, when the Beacon Journal reported students confirming attendance had plunged 33 percent year over year. It still has faculty members concerned for the university, which has seen total enrollment slip from more than 27,000 in the fall of 2013 to less than 25,200 in the fall of 2015.

“You just don’t see that in a major state university of 20,000 students,” said Daniel Coffey, an associate professor of political science who led a committee that wrote Akron’s Faculty Senate no-confidence resolution earlier this year.

Faculty members weren’t the only ones to take note of the drop. This month Moody’s Investors Service revised Akron’s credit outlook from stable to negative, a change it said reflected several years of falling enrollment and the smaller expected incoming freshman class. Moody’s continued to assign the university a bond rating of A1, a prime rating indicating the university has a strong ability to meet commitments. But a downgrade could come if Akron cannot stabilize enrollment, align its budgets and generate cash flow, the ratings agency said in a note.

Still, Moody’s had given Akron management high marks for financial work.

“Management's active budgetary oversight and concerted focus on expense containment help mitigate the revenue impacts of the expected enrollment decline in fall 2016,” Moody’s said in its note. “A more robust, centralized budget process was recently adopted to help control expense growth and inform budget decisions.”

Under Scarborough, Akron made some very visible moves geared toward containing costs. In July 2015 the university announced 215 job cuts and the elimination of its baseball team as part of a three-year plan to save $60 million. The cuts came on the heels of attempted increases in tuition and fees. Some faculty members and students criticized the direction of the cuts for a university that spends $8 million per year subsidizing its football program with little direct financial return to show for the cash.

Job cuts also led to concerns about outsourcing. Akron was cutting more than 50 jobs from its own student success division. It then decided to hire success coaches to supplement its own academic advising and counseling services under an $840,000 one-year pilot contract with a local start-up called Trust Navigator. The move was also criticized for Akron relying on an untested company.

Other events capturing attention included Akron eliminating the jobs of all University of Akron Press employees, then deciding to restore jobs for two employees.

The cuts weren’t the only change being put in place in the summer of 2015, however. Akron moved to rebrand itself as “Ohio’s Polytechnic University.” The new marketing came as politicians and other leaders pushed for applied training at the university level in order to ready graduates for the workforce. But it was also panned for the negative effect it could have on Akron’s arts and humanities programs.

Scarborough defended the change as necessary at the time -- something that could make Akron stand out from other generic regional state universities in the Midwest.

“The most risky path is the one that we were on,” he said. “The one where you are not identifying what is unique or strong about your university.”

Still, the change drew fury from alumni and others who reacted to reports Akron would change its name to Ohio Polytechnic Institute. Thousands signed an online petition against the name change, even as officials said the university had no plans to change its official name.

Effectively, Scarborough was trying to walk a line between keeping expenses in check and growing Akron beyond its roots in northeastern Ohio, an area experiencing population declines. He wanted to take advantage of the fact that Akron was traditionally strong in career-oriented programs, he said at the time. Yet he needed to balance planned new programs with a decline in tuition dollars -- even after years of capital investments totaling more than $600 million put pressure on the books.

“That’s a problem,” Scarborough said. “You’ve leveraged yourself, so you can’t afford to simply get smaller and be OK with that.”

In many ways, that summer of 2015 was a critical time for Scarborough’s presidency, as the different changes drew increasing amounts of attention and scrutiny. But Scarborough’s moves toward a larger university dated several months earlier, when he announced plans for a GenEd Core Pilot Program designed to draw in students with low-cost general education courses. The online-heavy program aimed to catch students by allowing them to pay half the amount for general education classes that they would at community colleges.

That pilot program was met with resistance from community colleges that feared it would erode their base of students and criticized it as misleading. Akron professors also worried the program would not be good for students early in their college careers, and that it would erode an important source of revenue for Akron.

Faculty members were not against trying new strategies, Coffey said. But many saw no coherent strategy taking shape.

“It’s not so much that he wanted to try different things,” Coffey said. “It’s that his entire leadership approach was based on the premise of, ‘We’re going to throw everything against the wall and see what sticks. Pushing every button is never a good idea.’ ”

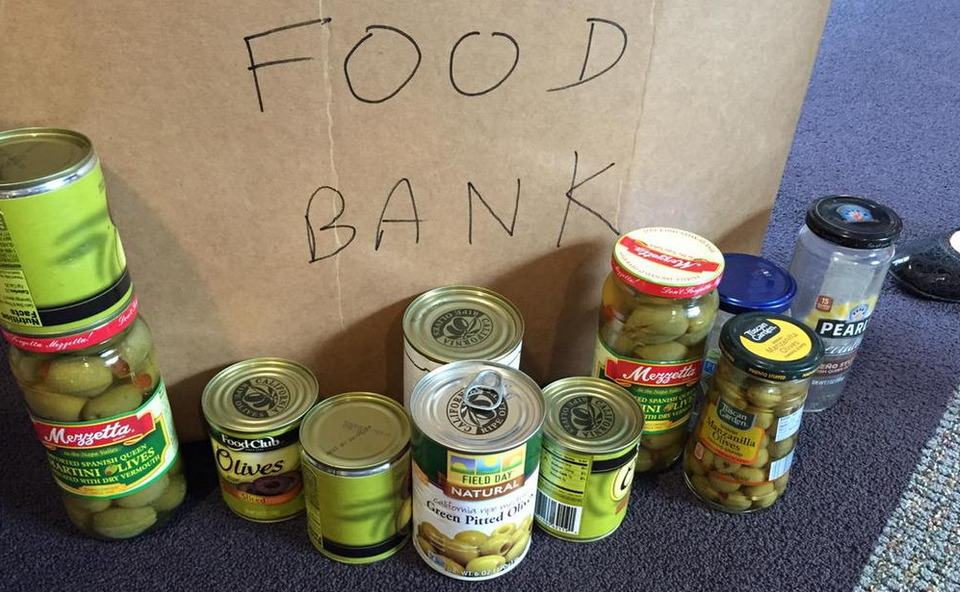

Scarborough then came under serious personal scrutiny later in 2015 for $951,000 in renovations to the university’s presidential home. An itemized list or expenses included numerous pricey items, with one in particular generating outrage: an olive jar costing $556.40. The olive jar became a symbol of misplaced priorities and the focus of protests, including one in which people donated olives for the jar -- which came without them.

Scarborough then came under serious personal scrutiny later in 2015 for $951,000 in renovations to the university’s presidential home. An itemized list or expenses included numerous pricey items, with one in particular generating outrage: an olive jar costing $556.40. The olive jar became a symbol of misplaced priorities and the focus of protests, including one in which people donated olives for the jar -- which came without them.

Criticism came even though the university said private money paid for the renovations and purchases. To many, the use of private funds was irrelevant since the university could have used contributions to support academic programs instead of furnishing the president's home.

Another emblematic controversy was over Akron negotiating a business deal with ITT Education Services. Akron would not discuss the reports in February. Documents later released and reported on by the Beacon Journal said a partnership had been on track to be announced early in January before falling apart. Scarborough and Pavloff sent an email at the end of April saying a deal was dead.

In February, faculty members voted no confidence in Scarborough by a tally of 50-2. Stated concerns included violations of shared governing principles, dropping enrollment, dispute over the scope of the university’s budget gap, cuts to key services on campus, plummeting donations, the polytechnic rebranding, cuts to tenure-track faculty numbers, hiring non-tenure-track faculty, hiring deans over the objection of faculty and search committees, outsourcing and disagreements within the university community stemming from Scarborough’s policies and an attempt to increase student fees that was rolled back after opposition and state legislative action.

Much of the friction can be read as a collision between the academic and business worlds. Although Scarborough’s time in universities and university systems dates to 1992, he started his career in accounting.

“He had a business background, and what works in business doesn’t work in academia,” said Constance Bouchard, a distinguished professor of medieval history and vice president of the Akron chapter of the American Association of University Professors.

“I’m sure he was frustrated too,” she said. “We didn’t act like workers. We talked back.”

Many of the initiatives put in place under Scarborough have been abandoned or walked back, Bouchard said. The Trust Navigator academic advising contract was abandoned last month. The ITT Tech deal never happened. The polytechnic branding has been scrubbed from many places.

But many at the university had lost faith. It became clear that new leadership would be necessary, said William Rich, an associate professor of law and chairman of Akron’s Faculty Senate.

“I think we got to the point where, in order for the university to change course and repair the damage that had been done to the university’s reputation, there needed to be a change in leadership,” Rich said. “I think the trustees and the president have recognized that.”

The question now is how Akron moves forward. The university is not releasing 2016 enrollment projections, but they’ll likely continue years of decline. Akron had 27,079 total students in the fall of 2013 and 25,865 in the fall of 2014 before slipping to 25,177 last fall. Its faculty numbers have fallen from 875 in November of 2014 to 822 in as of May this year. Staff totals dropped from 1,547 to 1,268 in the same time frame.

The university did not name an interim president Tuesday. An appointment will be made in the near future, it said.

For the time being, Rex Ramsier will fulfill the duties of president. Ramsier is interim senior vice president and provost.

The new leaders need to be able to mend fences, said John Zipp, a professor of sociology at the university and president of the Akron chapter of the American Association of University Professors.

“We would like an interim who has academic credentials, one who has come up through the ranks,” Zipp said. “I think for the interim we need to look inward. We need an internal candidate who has the support of the faculty, the staff, the community.”

The union wants the permanent president to emphasize the academic side of the university as well, Zipp continued.

“Someone who really has an understanding of the academic side,” Zipp said. “Who really understands in his or her bones what it means to be an academic.”