You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

New higher education cuts in Kansas slash more deeply from research universities, highlighting the question of whether large institutions should bear the brunt of declines in state funding in order to ease the burden on their smaller sister universities.

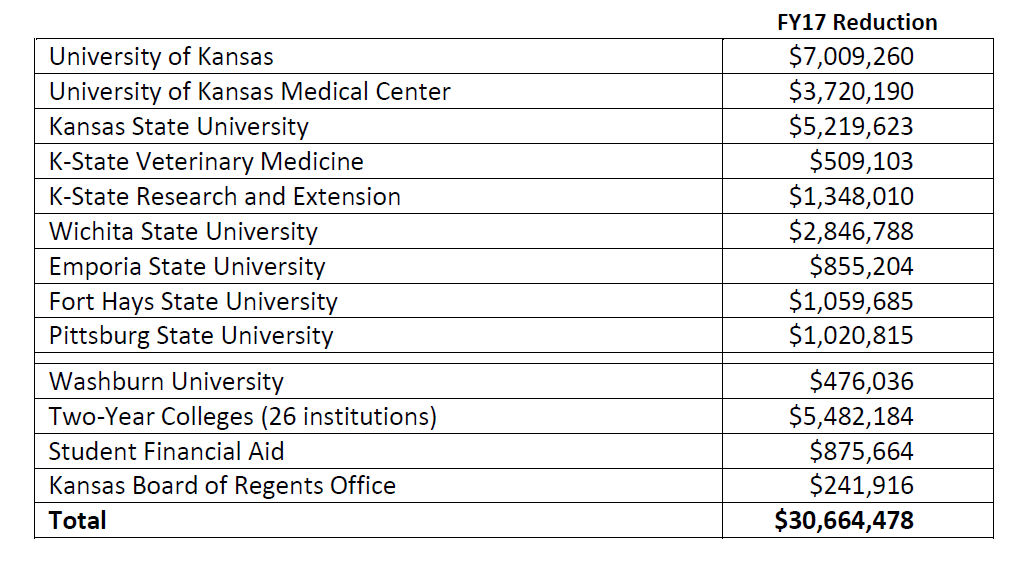

Kansas Governor Sam Brownback approved Wednesday a 4 percent, $30.7 million cut to the state’s higher education system for the upcoming 2017 fiscal year. The cuts in higher education funding were part of a larger batch of cutting totaling $97 million that also included deep decreases in Medicaid spending.

Cuts to state support are nothing new for Kansas’ university system, which includes six state universities, a municipal university, 19 community colleges and six technical colleges. The state has had to regularly chop spending in recent years amid declines in revenue during the tenure of Brownback, who pushed for deep tax cuts passed in 2012. But the latest round of cutting is notable in that lawmakers introduced a new formula changing the way higher education cuts translate to individual universities.

The new formula isn’t based on the amount of state funding each university receives or enrollments. It cuts a percentage of state funding based on their total operating budgets. As a result, universities that have more outside funding -- more research grants, higher tuition, larger endowments -- are seeing their state aid drop off more precipitously.

Effectively, that means the state’s two largest research universities, the University of Kansas and Kansas State University, are seeing the greatest hits, about 5 percent apiece. KU’s budget reduction totaled just over $7 million, plus the University of Kansas Medical Center saw a $3.7 million cut. K-State’s reduction was more than $5.2 million. The state’s other research university, Wichita State University, had its state support cut by 3.8 percent, $2.8 million. While landing federal research grants resulted in larger cuts for these universities, those grants are generally for specific research projects and not for the cost of educating undergraduates -- an expense typically supported by state governments at public universities.

Meanwhile, Kansas’ three other state universities saw smaller cuts, generally near 3 percent. Emporia State University lost $855,204. Fort Hays State University and Pittsburg State University each lost just over $1 million.

The distribution of the cuts has some at the larger universities protesting, saying they’re unfairly saddled with a majority of the hardship. The Kansas Board of Regents is unhappy as well, because it was not given the ability to decide how cuts are distributed. The new calculation’s biggest supporter is not backing down, however, arguing it’s an equitable move protecting smaller, more vulnerable institutions.

Leaders at KU and K-State blasted the new formula in early May shortly after it was proposed. They argued it punished their universities for being successful research institutions in a letter addressed to their schools’ alumni associations.

“This formula penalizes Kansas State University and the University of Kansas, whose all-funds budgets are higher because of our large research portfolios,” said the letter, which was signed by K-State Interim President General Richard Myers and University of Kansas Chancellor Bernadette Gray-Little. “In essence, this formula punishes K-State and KU for conducting research and successfully securing federal research grants that bring new dollars to Kansas.”

Andrew Bennett, a professor of mathematics who is K-State’s Faculty Senate president, echoed those sentiments in an interview Thursday. The Faculty Senate has not voted on an official position regarding the cuts, but many professors are disappointed, he said.

“We’ve been left with a sense that the Legislature doesn’t necessarily understand -- if we have research dollars, we can’t move those research dollars,” he said. “They have been given to us by agencies to carry out certain research grants. We can’t use those funds to substitute for state dollars to teach freshmen calculus.”

But the lawmaker who introduced the budget cut formula, State Senator Jacob LaTurner, said it is fair. LaTurner is a Republican whose district in southeastern Kansas includes Pittsburg State University. The new calculation is an equitable action when higher education cuts are necessary, he said.

Across-the-board cuts based on state spending disproportionately hurt smaller universities, LaTurner said. He added that he would not apologize for doing his job, representing his district and watching out for an institution like Pittsburg State.

Allowing the Board of Regents to decide how to carry out spending cuts leaves open the possibility it will favor the research universities, LaTurner said.

“The regents have an attitude that we’ll all live and die together -- that's what they portray,” LaTurner said. “In fact, it is, ‘Everybody be quiet and we’re going to do things for the big universities.’”

Regents, unsurprisingly, see the landscape differently. They can make a more informed decision than a legislatively imposed formula, said Shane Bangerter, chair of the Kansas Board of Regents.

“From the system vantage point, we just think it’s a lot better policy for those kinds of decisions to be made by the governing board,” Bangerter said. “We have an opportunity to weigh programs and weigh the effect of each cut on each institution, rather than to make somewhat of an arbitrary decision in regards to who should feel the pinch worse than the other.”

Bangerter compared the cuts to research universities to cuts those institutions would have experienced under previous reduction allocations. Kansas loses about $1.5 million more, he said. K-State loses $1.1 million. Wichita State is roughly even, and other institutions saw lesser cuts because of the change.

“It comes out of everybody,” Bangerter said. “It’s just a little different proportion than if they’d done it the way they did in the past.”

Regents had been expecting a 3 percent cut, meaning the 4 percent reduction approved Wednesday was deeper than expected. The governor also approved the cuts on the same day the Board of Regents heard state universities’ 2017 tuition proposals. It’s now possible those tuition proposals could have to change, particularly at the large research institutions hit the hardest.

The University of Kansas had asked to increase standard in-state undergraduate tuition and fees by 4 percent, or $200.50, to $5,228.75 per semester. K -State had asked for a hike of 4.9 percent, or $227.45, to $4,902.25.

Both universities could come to rely more on other revenue sources. Out-of-state and international students bring in much higher amounts of revenue. KU had proposed standard undergraduate out-of-state 2017 tuition and fees rising 4 percent to $12,847.25. K-State had proposed a 4.9 percent hike to $12,292.75.

“There’s a relationship between state funding and tuition,” Bangerter said. “This is a national trend. Certainly we’ve seen it in all of our institutions, and a huge increase in the effort to attract philanthropic giving to the endowment, for example.”

There is some merit to the argument that research universities are taking on a new burden under the new formula, said Andy Carlson, a senior policy analyst at the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association. But there is also merit to the idea that they can better compensate for state funding cuts by attracting higher-paying out-of-state and international students, he said. Institutions in many states have followed that strategy when times were tight in recent years.

“That would certainly affect the research institutions more significantly, but I think it’s safe to say that they probably have a lot more access to tuition revenue to kind of cover their operations,” Carlson said.

Ultimately, the fairest way to make cuts looks different depending on perspective, said Thomas Harnisch, director of state relations and policy analysis at the American Association of State Colleges and Universities. The Kansas situation stood out to him for another reason as well -- timing. The change in funding-cut allotment came relatively late in the process, he said. And it wasn’t clear until the end whether Brownback would use a line-item veto to strike the change from the books and allow cuts to be allotted in another way.

“I generally don’t see state lawmakers changing the game, changing the ground rules, this far into the session,” Harnisch said. “Usually they know in advance how the cuts are going to be distributed.”

Kansas is not the only state where the issue of support for smaller universities contrasted with funding for larger ones. In Illinois, colleges and universities have struggled amid a prolonged budget battle this year. Lawmakers approved some funding in April to keep state colleges and universities open through the summer.

But smaller institutions felt an outsize impact, Harnisch said. Chicago State University eliminated jobs for 300 employees this month.

“There were institutions on the front line, like Eastern Illinois and Chicago State, that just didn’t have the cushion,” Harnisch said. “Chicago State was near closing. Then you have institutions like the University of Illinois, which has a larger cushion to withstand some of the cuts.”

Back in Kansas, the latest cuts aren’t the only ones this calendar year -- Brownback in February announced a $16 million cut from higher education to close a budget gap for the current fiscal year ending in June.

And the threat of future cuts still looms. Brownback noted a state Supreme Court case over K-12 funding could force $40 million or more in additional spending. That spending could lead to additional higher education cuts, the governor said in a legislative message.

However it plays out, the uncertainty is hurting universities, said Tom Beisecker, chair of the department of communication studies and Faculty Senate past president at the University of Kansas. He anticipates being unable to fill open positions and losing top faculty members to competing institutions.

“If you encounter budget cuts, you have all kinds of decisions you have to make in terms of allocations of department resources, university resources,” Beisecker said. “It’s very difficult to engage in long-term planning, because the long-term planning keeps having to be readjusted downward.”

Kansas was also one of only a handful of states to see a decline in state funding for higher education between the 2015 and 2016 fiscal years, according to an annual study by the Center for the Study of Education Policy at Illinois State University and the State Higher Education Executive Officers. Kansas funding fell 1.2 percent in the time period, it said.

State funding for higher education in Kansas has decreased by 8.6 percent, or nearly $100 million, since 2007-08, according to the Board of Regents.