You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Tenure denials happen all the time, and they’re most often accepted by fellow professors and students as an unpleasant byproduct of the tenure system. But sometimes such denials rock an institution. That’s what’s happening now at Dartmouth College, regarding the failed bid of Aimee Bahng, an assistant professor of English who faculty members and students alike say deserves a permanent position on campus. Beyond Bahng, concerned professors say the case speaks to bigger questions about commitments to minority faculty members, interdisciplinary research and shared governance at Dartmouth and beyond.

“The issue of faculty governance at Dartmouth is a heated one, and it extends to broader issues than [this] tenure case -- though that has been a trigger for many of the broader discussions we're having now -- and though it is widely perceived as unjust and shortsighted,” said Annelise Orleck, a professor of history at Dartmouth who criticized the tenure decision at a recent town hall about the findings of a campus climate survey. Several hundred faculty members, students and staff reportedly were in attendance.

In addition to the town hall, professors and students have taken their protest to Twitter under the hashtags #fight4facultyofcolor and #dontdoDartmouth; the latter features students and academics advising would-be applicants to avoid the institution.

Public details on Bahng’s bid are few, and she did not respond to a request for comment. But fellow faculty members confirmed that she was unanimously approved by the department's tenure committee. Her bid fell short higher up in review chain, which includes the associate dean, the dean of the faculty and the arts and sciences faculty’s Committee Advisory to the President.

Dartmouth says it’s bound by confidentiality surrounding the tenure process, but that unanimous department decisions don’t always lead to tenure. And that’s true -- the departmental tenure committee merely makes a recommendation. Yet at many institutions, it’s rare for a unanimous faculty vote to be overturned.

Orleck and others on campus say Bahng’s case is similar to several others in recent years, in which department votes for tenure and unanimous recommendations for tenure by outside reviewers are overruled by deans or the Committee Advisory to the President. A number allegedly have been faculty members of color who were respected by their colleagues and students. One such case is that of Derrick White, now a visiting associate professor of history. White did not immediately respond to a request for comment, but his name and failed tenure bid last year -- despite the unanimous vote of his departmental peers and outside reviewers -- have been mentioned in many of the conversations about Bahng.

In short, the most recent case appears to be something of the last straw on a campus that’s already facing criticism for what many see as a lack of commitment to diversity. According to a recently released climate survey report, 21 percent of faculty, student and staff respondents said they’d experienced exclusionary, intimidating, offensive or hostile conduct. Some 16 percent of those respondents felt it was based on the their ethnicity, and 28 percent said it was based on their sex or gender; respondents of color were much more likely to report that the behavior was linked to their ethnicity.

Faculty and staff respondents also reported observing unjust hiring (23 percent), unfair or unjust disciplinary actions (15 percent), or unfair or unjust promotion, tenure or job reclassification (24 percent).

At the same time, 70 percent of all survey respondents said they were comfortable or very comfortable with the climate at Dartmouth over all. Some 73 percent of faculty and staff respondents said they were at least comfortable within their departments. And administrators have pointed out that the climate survey is a starting point for improvements.

Some are already underway. The college announced in February that it was creating three linked working groups to review existing efforts to foster diversity among faculty members, staff and students.

"The full realization of this community’s diversity cannot take the form of isolated initiatives; it must inform all of our work at Dartmouth," President Phil Hanlon and Provost Carolyn Dever said in a statement at the time. "Today, people and programs across campus dedicate themselves to making Dartmouth an inclusive institution in which differences -- of race and ethnicity, gender and sexual identity, socioeconomic status, and thought, among others -- are recognized, valued and celebrated. While these efforts are crucial to our success, we must make sure that they are fully aligned, well coordinated, clearly communicated and understood by all."

Dartmouth has also committed to increasing underrepresented minority faculty members to 25 percent of the tenure-track faculty by 2020; underrepresented minorities currently make up 16 percent of the faculty overall. The college has established a faculty diversity recruitment fund from a pool of $22.5 million in endowment dollars, with $1 million allocated annually. Arts and sciences departments will have recruited eight new professors who contribute to diversity goals by fall, according to information from the university, and associate deans meet annually with all junior faculty members to assess their progress on teaching, scholarship and service.

A spokesperson, Diana Lawrence, also said that a minority faculty member was tenured just weeks ago in the women's and gender studies department.

Trouble With Retention

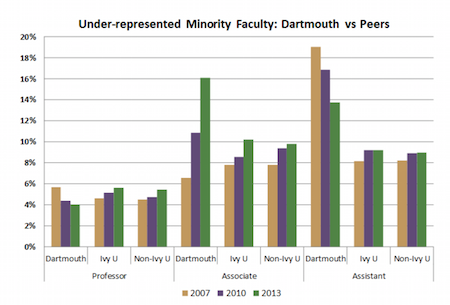

Yet even Dartmouth admits it has a problem retaining faculty members of color. “In the last decade Dartmouth has had mixed results in its recruitment, development and retention of [underrepresented minority] faculty,” reads a report on faculty diversity published in January. “For example … in 2007 we led our Ivy [League] and non-Ivy peers in percentage of [underrepresented minority] full professors, but we now trail our peers, with no [underrepresented] full professors in the social sciences, English or engineering. As of 2013, we had higher overall percentages of [underrepresented] assistant and associate professors compared to our peers, but no [underrepresented] assistant professors in the sciences.”

The report says that when overall underrepresented minority numbers are low, “all departures, for any reason, are felt significantly across the campus and fuel the perception of unfairness. Many are skeptical of Dartmouth’s commitment to diversity and inclusion, noting longstanding concerns about the campus climate for [underrepresented] faculty. … Regrettably, these patterns of dissatisfaction particularly for faculty of color and other underrepresented groups continue at Dartmouth, and indeed became more evident in the fall of 2015 as students at Dartmouth and across the country raised the alarm about the lack of faculty of color in higher education.”

Such events, which tied into student-led protests over race relations on numerous other campuses and the greater Black Lives Matter movement, included a “Blackout” march across campus in November.

“Our own evidence makes it clear that we are not doing enough to systematically address the challenge of making our community an inclusive one that recruits, promotes and values the excellence that comes from a robust diversity of people and perspectives,” reads the diversity report.

Beyond tenure denials, some faculty members of color have left Dartmouth on their own. In a Facebook post about the departures, Treva C. Ellison, a lecturer in geography and women, gender and sexuality studies, wrote that the “lack of critical faculty here always means that any new person hired who can feel what direction gravity pulls in is going to be inundated with more work than their white cisgendered male counterparts and other zero-G hires.” Dartmouth doesn’t have a “diversity problem,” she added, “rather, the temporary, precarious and disavowed labor of people of color at Dartmouth is their purposeful and intentional diversity solution.”

Some scholars see other things at play in Bahng’s case. Cynthia Wu, an associate professor of transnational studies specializing in Asian-American studies at the State University of New York at Buffalo, wrote to Hanlon to ask him to reconsider the tenure denial, saying, “for many of us in the field of Asian-American studies, this is not an individual matter. It is systemic.” (Bahng specializes in Asian-American studies.)

In 12 years as a professor, she wrote, “I have witnessed the dismantling of Asian-American studies through institutional refusals to retain faculty who teach and do research in this area. … I lament that so many specialists in Asian-American studies have fallen through the cracks because of these institutional failures.”

One cause of such failures, she wrote, is that faculty members who specialize in fields that foreground race, gender and sexuality often have above-average teaching and service workloads. “Students disproportionately seek us out for mentoring,” Wu wrote. “We are disproportionately called upon to serve on committees pertaining to diversity initiatives. This increased workload undoubtedly impacts our ability to spend as much time on our research as our peers.”

Another reason is that research on race, gender and sexuality “has less cultural capital,” Wu said. “To put it bluntly, it is less respected. It also tends to be interdisciplinary and, therefore, misunderstood in an academy that fiercely defends its disciplinary boundaries despite lip service to the contrary. Even if we do match or surpass our peers in terms of research output, our work is commonly regarded less favorably and/or less knowledgeably. From a careful perusal of Bahng’s [curriculum vitae], it appears that she has exceeded the expectations for research at an institution that values it highly.”

Jeff Sharlet, an associate professor of English at Dartmouth, said in an interview that he was surprised Bahng hadn’t earned tenure precisely because her research and teaching are so innovative. A current book project is a collaboration among numerous scholars, and a team-taught course on the Black Lives Matter movement attracted national media attention.

Sharlet and other English professors met with administrators on Monday to discuss Bahng’s case. He said he couldn't discuss the outcome of the meeting, but that he’d hoped to highlight “questions of how we evaluate work, especially at a time when colleges increasingly are turning toward analytics that give you various index numbers about publications in leading scholarly journals. What happens when you directly buck that system and say, ‘Let’s challenge the cult of authorship,’ as [Bahng] and her collaborators did. … Any then what do we do with [her] innovative Black Lives Matter course?” Not only was it socially pertinent, he said, “but it was really exciting pedagogy -- to the point that it becomes research, and where we’re thinking about knowledge production.”

Sharlet added, “We have a cutting-edge scholar negotiating this work, and I think it’s a loss for us to lose that.”

Questions of quantification of research also worry Orleck, the history professor, who pointed to Dartmouth’s contract with Academic Analytics as an emerging point of concern. The productivity indexing company already has sparked faculty resolutions against it at Rutgers University.

Regarding Wu’s concerns about Asian-American studies, students have been pushing for a new, separate program in the field; currently Asian studies is housed along with Middle Eastern studies. Wu seemed agnostic on that point, saying there were pros and cons to both arrangements.

Asked if Asian-American faculty members might have also have been neglected in recent campus diversity efforts aimed at increasing the number of underrepresented minorities, Wu said she didn’t think it was “useful to pit Asian-American faculty against other faculty of color. If anything, these calls for faculty diversity benefit everyone. When African-American and Latino faculty leave institutions in droves, it affects us, too. It affects everyone.”