You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The first major update in seven years of a database on grade inflation has found that grades continue to rise and that A is the most common grade earned at all kinds of colleges.

Since the last significant release of the survey, faculty members at Princeton University and Wellesley College, among other institutions, have debated ways to limit grade inflation, despite criticism from some students who welcome the high averages. But the new study says these efforts have not been typical. The new data, by Stuart Rojstaczer, a former Duke University professor, and Christopher Healy, a Furman University professor, will appear today on the website GradeInflation.com, which will also have data for some of the individual colleges participating in the study.

The findings are based on an analysis of colleges that collectively enroll about one million students, with a wide range of competitiveness in admissions represented among the institutions. Key findings:

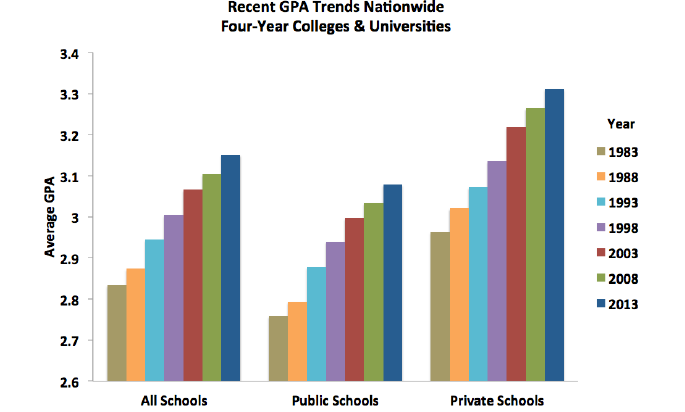

- Grade point averages at four-year colleges are rising at the rate of 0.1 points per decade and have been doing so for 30 years.

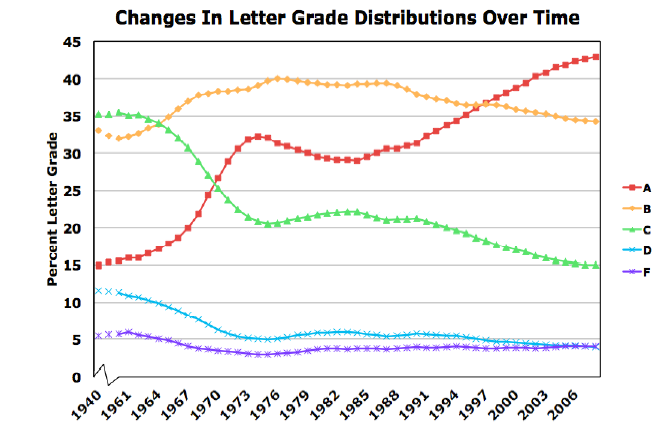

- A is by far the most common grade on both four-year and two-year college campuses (more than 42 percent of grades). At four-year schools, awarding of A's has been going up five to six percentage points per decade and A's are now three times more common than they were in 1960.

- In recent years, the percentage of D and F grades at four-year colleges has been stable, and the increase in the percentage of A grades is associated with fewer B and C grades.

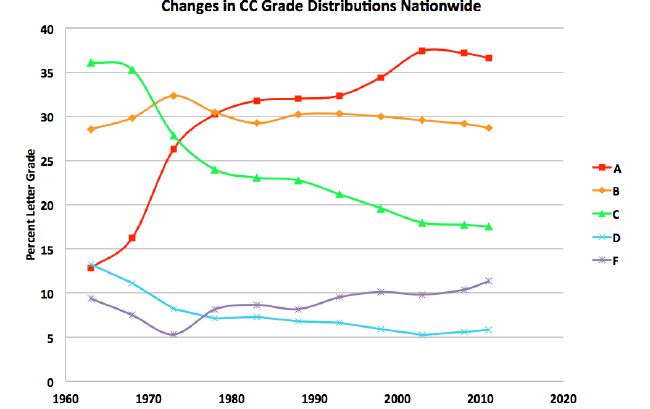

- Community college grades appear to have peaked.

- At community colleges, recent years have seen slight increases in the percentages of D and F grades awarded. While A is still the top grade (more than 36 percent), its share has gone down slightly in recent years.

Here are some of the graphics being released today, appearing here via permission of GradeInflation.com, which show the various trends for grade point averages at four-year colleges and universities, grade distribution at four-year colleges and universities, and grade distributions at community colleges:

The trends highlighted in the new study do not represent dramatic shifts but are continuation of trends that Rojstaczer and many others bemoan.

He believes the idea of "student as consumer" has encouraged colleges to accept high grades and to effectively encourage faculty members to award high grades.

"University leadership nationwide promoted the student-as-consumer idea," he said. "It's been a disastrous change. We need leaders who have a backbone and put education first."

Rojstaczer said he thinks the only real solution is for a public federal database to release information -- for all colleges -- similar to what he has been doing with a representative sample, but still a minority of all colleges. "Right now most universities and colleges are hiding their grades. They're too embarrassed to show them," he said. "As they say, sunlight is the best disinfectant."

Not all scholars of grading and higher education share Rojstaczer's views, although most agree that grade inflation is real.

A 2013 study published in Educational Researcher, "Is the Sky Falling? Grade Inflation and the Signaling Power of Grades" (abstract available here), argued that a better way to measure grade inflation is to look at the "signaling" power of grades for employment (landing prestigious jobs and higher salaries). To the extent the relationship between earning high grades and doing better after college is unchanged -- and that’s what the study found -- the "value" of grades can be presumed to have held its ground, not eroded.

Debra Humphreys, senior vice president for academic planning and public engagement at the Association of American Colleges and Universities, said she looks at lots of data to suggest "an underperformance problem," which raises the question of why grades continue to go up. AAC&U is one of the leaders of the VALUE Project, which aims to have faculty members compare standards for various programs with the goal of common, faculty-driven expectations about learning outcomes. Humphreys said agreement on learning outcomes and assessment is important because so much of what goes on in grading is "so individual."

"It remains largely a solo act, with no shared program standards for what counts as excellent, good, average or inadequate work," she said. "So faculty have no firm foundation to stand on when they go against the trend and assign lower grades."

Community College Students and Faculty Members

In his analysis, Rojstaczer notes that community colleges have some characteristics that might make them as prone to grade inflation as are four-year institutions (and he considers community college grades high, too, even if they aren't still rising). For example, he notes that many community college leaders embrace the student-as-consumer idea just as do four-year college presidents. And community colleges rely on adjunct instructors, many of whom lack the job security to be confident in being a tough grader, since students tend to favor easier graders in reviews.

Rojstaczer thinks that, to understand grade inflation, one needs to look at the student body at two-year colleges, which he characterizes as less spoiled than those at four-year institutions. "One factor may be that tuition is low at these schools, so students don’t feel quite so entitled," he writes. "Another factor may be that community college students come, on average, from less wealthy homes, so students don’t feel quite so entitled."

Thomas Bailey, George and Abby O’Neill Professor of Economics and Education and director of the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University, agreed via email that he also thinks tuition and student expectations may play a role.

"I would imagine that four-year colleges are more likely to compete on the basis of grades than community colleges," he said. "Most community college students go to the closest college, so they don't shop around as much, so there would be less chance that they would benefit from a reputation of high grades. In terms of the notion of entitlement, it might be that students who pay more would feel more willing to demand some sort of accommodation. I believe that among four-year colleges, grade inflation is higher for privates, who charge more, than it is for publics."