You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

Physics is often characterized as having a tough climate for women, of whom there are still relatively few working in the field (even compared to the other sciences). But the American Physical Society has made inroads in addressing the issue, offering site visits sponsored by its Committee on the Status of Women in Physics, for example, as well as by its Committee on Minorities. But what about the climate for lesbian, gay, transgender and bisexual physicists? Faced with an absence of data on the matter, the society created an ad hoc committee to assess working conditions for these populations and establish recommendations based on its findings.

The committee’s report, “LGBT Climate in Physics: Building an Inclusive Community,” was released Tuesday at the society's March meeting, in Baltimore. Major findings from climate survey targeting LGBT physicists on which the report was based in part include that women, and especially gender-nonconforming and transgender respondents, experience and observe harassment at higher rates than their male counterparts. That gendered dynamic also was observed in levels of discomfort in the workplace and feelings about whether one’s workplace was supportive.

More than 20 percent of self-identified LGBT respondents to a climate survey reported experiencing exclusionary behavior in the past year, while 40 percent reported observing exclusionary behavior due to gender, gender expression, gender identity, sexual orientation or sexual identity. Among transgender respondents, those response rates were 49 percent and 60 percent, respectively.

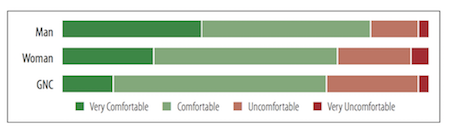

Perceptions of Departmental Climate Among Male, Female and Gender-Nonconforming Respondents

Transgender Concerns

“If there’s anything that's got to be taken away from this report, it’s that we need to be thinking about how we can be including people who are [transgender and gender-nonconforming] and making a better environment for those folks,” Ramón S. Barthelemy, a Science and Technology Policy Fellow at the American Association for the Advancement of Science and report committee member, said during a news conference Tuesday.

Transgender and gender-nonconforming physicists may face particular challenges, according to the report, such as lack of health benefits or access to safe bathrooms, inappropriate use of pronouns, and a “profound” lack of respect and awareness, according to the paper.

Women who completed the climate survey targeted at LGBT physicists experienced exclusionary behavior (such as sexual harassment, verbal harassment, homophobic comments) at three times the rate of men, and open-ended and interview responses suggested that LGBT people of color face particular challenges, the report says.

Michael L. Falk, professor of materials science and engineering at Johns Hopkins University and committee chair, said respondents who experienced the most problematic climates seemed to be those with other, traditionally marginalized identities, but that it was hard to untangle exactly what was motivating what kinds of discrimination.

Climate concerns may also have implications for employee retention, according to the report. One-third of climate survey respondents reported considering leaving their workplace or institution in the last year, and reporting adverse climate or observing exclusionary behavior in one’s workplace or university correlated highly with a consideration of leaving.

Many LGBT physicists feel isolated and would benefit from having more allies, according to the report. But visible allies are often hard to find.

Monica Plisch, associate director of education and diversity at the society, said some respondents to a separate, general membership survey that included a question on LGBT status said they didn’t understand what it had to do with physics -- a telling response in and of itself.

The People Behind the Physics

“Sometimes the physics is so exciting that we forget it’s people who do the physics,” she said. “But people are at their best when they feel safe and supported. … This gets at what we should be caring about as a professional society.”

The committee worked for 18 months on the report, gathering data by various means, including the climate survey targeted to LGBT physicists and a handful of in-depth follow-up interviews, discussion forums, and the question on the general membership survey.

Some 324 people responded to the climate survey, which targeted LGBT physicists in a “snowball” method, through peers. Most (84 percent) worked or studied in academe. About half were men, about one-third were women and 8 percent identified as gender nonconforming.

In the general membership survey demographic question (sent to a random sample of society members), just 2.5 percent of total respondents identified as LGBT over all, and 14 percent preferred not to provide such information. But U.S. respondents were twice as likely (3 percent) to answer as non-U.S. respondents. Respondents between 18 and 25 years of age were significantly more likely than the overall population to identify as LGBT, at 16 percent, suggesting a generational shift in comfort disclosing their status (just 6 percent of respondents in that age group declined to provide an answer).

Committee members found that LGBT physicists face uneven protection and support for legislation and policies, both in the U.S. and abroad. Some 50 percent of survey respondents rated their campus or workplace policies as “highly supportive” or “supportive,” while 30 percent characterized them as “uneven,” “lacking” or “discriminatory.” Only 40 percent of transgender respondents said their workplaces were supportive to some degree.

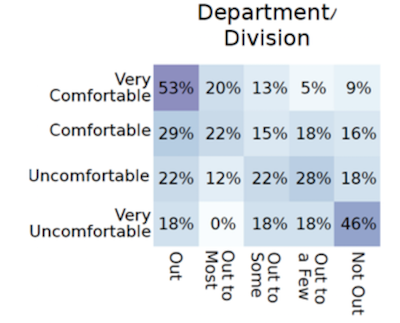

In terms of overall climate, 15 percent of men, 25 percent of women and 30 percent of transgender or gender-nonconforming physicists rated their departments as “uncomfortable” or “very uncomfortable.” About half were out to their co-workers, while the other half were only out to some, few or none. Outness and comfort at work correlate highly.

Some 40 percent of climate survey respondents agreed with the statement that employees are expected not to act “too gay,” while 45 percent disagreed with the idea that coworkers were as likely to ask kindly about heterosexual relationships as same-sex ones.

What the American Physical Society Can Do

The report includes several recommendations for the society:

- Ensure a safe and welcoming environment at society meetings, including by establishing written best practices on inclusion and by applying its Code of Conduct.

- Address the need to systematically accommodate name changes for transgender physicists in publication records.

- Develop advocacy efforts on LGBT inclusion, such as by issuing a statement on the inclusion and fair treatment of LGBT people in physics that supports nondiscrimination policies and legislation.

- Promote LGBT-inclusive practices in academe, labs and industry, including by promoting the best-practices guide developed by the group lgbt+physicists and by developing a training program on mentorship and other matters.

- Adopt LGBT-inclusive mentoring programs, including by recording best practices and creating a professional network or LGBT mentors and mentees.

- Support the establishment of a forum on diversity and inclusion that would promote a more inclusive, diverse and “equitable” society for all physicists, including those who identify as LGBT, women, racial and ethnic minorities, those with disabilities and others.

Kate Kirby, executive director of the society, said in a brief comment that the organization is committed to inclusivity, and that its governing board will consider the recommendations in full next month.