You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Whether adjunct faculty members teaching online receive professional training, written policies for how to interact with students and opportunities to customize their courses varies greatly from one college to another, a new study has found.

The study, a collaboration between the WICHE Cooperative for Educational Technologies (WCET) and the online program management company the Learning House, sheds light on two growing areas of higher education: courses where most or all of the instruction is delivered online, and courses taught by adjunct faculty members. But while more adjunct instructors are teaching online this year than before, the study still suggests the use of adjunct labor in online education is decentralized and, at some colleges, only lightly supervised.

The two organizations this summer partnered to survey 202 administrators involved in online education -- including deans, directors and provosts -- at two- and four-year institutions. The full results will be presented this week at the WCET Annual Meeting in Denver.

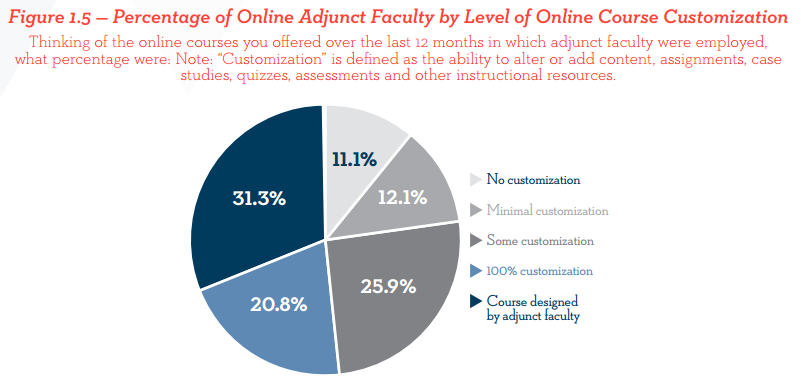

The study describes a “fundamental divide among institutions” about how they manage their adjunct faculty members. The clearest example of that divide can be seen in the level of customization colleges allow in their online courses. About half of the surveyed administrators (52.1 percent) said the adjunct instructors are free to design their own courses or tweak the assignments, assessments and content. The remaining respondents said they allow only some or minimal customization -- or none at all.

In an interview, Russell Poulin, WCET director of policy and analysis, called those approaches to online education “differences in philosophy.”

“There’s sort of a debate in the online world about which way you should go,” Poulin said. On one hand, he said, “there are those who are very interested in making sure that all students receive the same information, the same experience, and that they want to have everything set for the new faculty person.” On the other, “there are others who believe that the courses are the purview of the faculty person and whatever they bring to it,” he said.

Another divide can be seen in the training and professional development programs colleges offer. The surveyed administrators were more likely to say their institutions require online faculty members to complete orientation sessions on topics such as academic and student policies (62 percent), support services (61 percent) and the technology used at the college (47 percent) than instructor-led or self-paced sessions on effective online teaching methods (35 percent and 26 percent, respectively).

About one-tenth of the respondents (9 percent) said they don’t require adjunct faculty members to complete any training. While small, the share is “disconcerting,” the authors write. Even if those institutions only recruit experienced adjunct faculty members, they point out, the instructors may not be aware of policies specific to a department, college or campus.

“There’s such a wide variety,” said David L. Clinefelter, chief academic officer at the Learning House. “A couple of the institutions I talked to have thorough training programs before [faculty members] teach their first online class, and … close support systems as they are teaching. Other ones do almost nothing. They give them a book, put them in a class and check in at the end.”

Such anecdotes are the exception, not the norm, however. Clinefelter and Poulin said most colleges they surveyed are clustered somewhere in middle between offering little to no faculty training and having an extensive program in place.

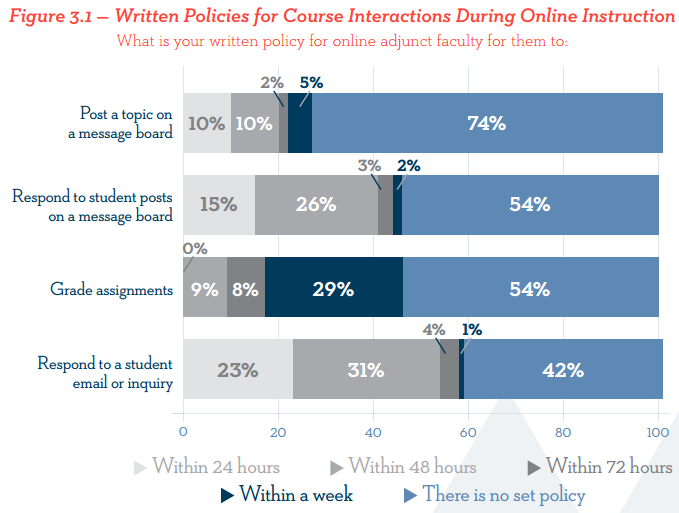

Even though the study suggests colleges are most likely to stress policy in the training programs they do offer to online adjunct faculty members, many lack institutional policies that dictate how instructors are expected to interact with students. More than half of respondents said they do not have set policy on how quickly instructors should grade assignments on respond to student forum posts (both 54 percent), and nearly three-quarters (74 percent) said they don’t have requirements in place for how often instructors should start new discussions online.

Those responses may indicate that administrators are leaving those decisions up to smaller units, and the survey results suggests a preference for a decentralized approach to managing online adjunct faculty members. More than half of respondents (53 percent) said individual colleges and departments are responsible for hiring adjunct instructors, compared to 28 percent who said hiring is handled by a centralized unit. The remaining respondents said they use a mixed approach.

“At large institutions, what is done with supporting and hiring adjuncts is dispersed all across campus,” Poulin said. But communication between those different colleges and departments is key to making that approach work, he said. If they don’t coordinate, a college may hire an adjunct instructor another college fired, or multiple colleges may hire the same person, he said.

Colleges are increasingly turning to adjunct faculty members to teach online, the survey results show. In the past year, 25 percent of respondents said their online adjunct population has increased by more than 5 percent, 31 percent grew the population by less than 5 percent and 39 percent reported no change. Only 6 percent of the surveyed administrators said they decreased the number of adjunct instructors teaching online. The report does not make an attempt to count the total number of adjunct faculty members teaching online, however.

In addition to growth, college also reported some stability. About two-thirds of respondents (69 percent) said they turn over less than 10 percent of their online adjunct workforce on a year-to-year basis. Of the 31 percent that reported a turnover rate higher than 10 percent, only 5 percent said the rate is higher than 20 percent.

Maria Maisto, president of the national adjunct advocacy group New Faculty Majority, said the conveniences of online education -- for example the lack of a commute to campus or set times when the classes meet -- may be leading more adjunct instructors to stay with the same employer. Others may choose to do so because of the time it takes to set up an online course or personal conflicts that prevent them from teaching in person, she said.

“[Teaching online] is often the only option for adjuncts who have significant family responsibilities,” Maisto said in an email.

Maisto also called for more information about how online adjunct instructors are compensated, a topic that the study does not touch on. She said she was not surprised by the findings on professional development and training.

“Ultimately the survey shows that we are right to be concerned about the quality of higher education when institutions refuse to provide the majority of the instructors who provide that education with the basic support that they need, both online and in person,” Maisto wrote. “The existing system cheats both adjuncts and their students.”