You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

Plagiarism detection software from vendors such as Turnitin is often criticized for labeling clumsy student writing as plagiarism. Now a set of new tests suggests the software lets too many students get away with it.

The data come from Susan E. Schorn, a writing coordinator at the University of Texas at Austin. Schorn first ran a test to determine Turnitin’s efficacy back in 2007, when the university was considering paying for an institutionwide license. Her results initially dissuaded the university from paying a five-figure sum to license the software, she said. A follow-up test, conducted this March, produced similar results.

Moreover, the results -- while not a comprehensive overview of Turnitin's strengths and weaknesses -- are likely to renew the debate among writing instructors about the value of plagiarism detection software in the classroom.

“We say that we’re using this software in order to teach students about academic dishonesty, but we’re using software we know doesn’t work,” Schorn said. “In effect, we’re trying to teach them about academic dishonesty by lying to them.”

Turnitin did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

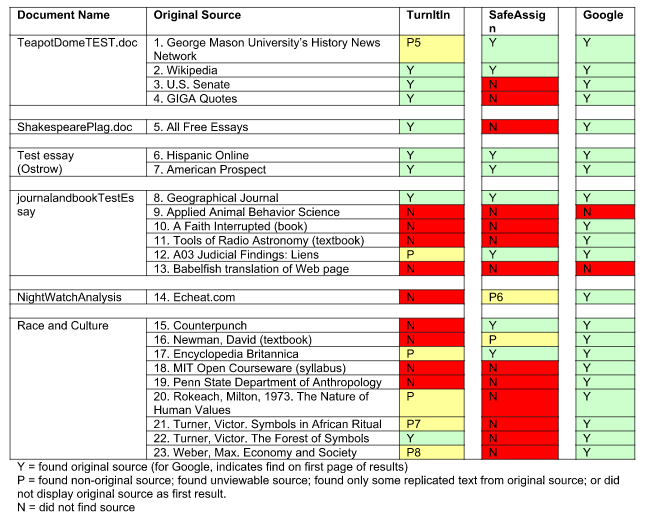

For the 2007 test, Schorn created six essays that copied and pasted text from 23 different sources, which were chosen after asking librarians and faculty members to give examples of commonly cited works. Examples included textbooks and syllabi, as well as websites such as Wikipedia and free essay repositories.

Of the 23 sources, used in ways that faculty members would consider inappropriate in an assignment, Turnitin identified only eight, but produced six other matches that found some text, nonoriginal sources or unviewable content. That means the software missed almost two-fifths, or 39.34 percent, of the plagiarized sources.

SafeAssign (the product UT-Austin ended up choosing, as it was bundled with the university's learning management system) fared even worse. It missed more than half, or 56.6 percent, of the sources used in the test. Mark Strassman, Blackboard's senior vice president of industry and product management, said the company has since "changed the match algorithms … changed web search providers" and "massively" grown the database of submissions SafeAssign uses.

Google -- which Schorn notes is free and worked the fastest -- trounced both proprietary products. By searching for a string of three to five nouns in the essays, the search engine missed only two sources. Neither Turnitin nor SafeAssign identified the sources Google missed.

As UT-Austin recently replaced its learning management system, it also needed to replace its plagiarism detection software. Schorn therefore conducted the Turnitin test again this March. Out of a total of 37 sources, the software fully identified 15, partially identified six and missed 16. That test featured some word deletions and sentence reshuffling -- common tricks students use to cover up plagiarism.

Schorn agreed to share results from both tests, which have previously only been shared with other writing instructors, with Inside Higher Ed. Read the 2007 report by clicking here, and the follow-up report here.

A 'Dog-Bites-Man Twist'

Even as Turnitin and its lesser-known competitors are widely used in the K-12 and higher education markets, professional organizations for writing instructors continue to be critical of the role of computers in evaluating student writing. Instructors themselves often wrestle with how to strike the balance between punishing students for plagiarism and letting them learn through trial and error how to correctly use outside sources.

The Council of Writing Program Administrators has noted that “teachers often find themselves playing an adversarial role as ‘plagiarism police’ instead of a coaching role as educators.” As a result, the “suspicion of student plagiarism has begun to affect teachers at all levels, at times diverting them from the work of developing students’ writing, reading and critical thinking abilities,” the organization wrote in a statement on best practices from 2003.

But that statement also explains one of the reasons why so many millions of teachers and faculty members use plagiarism detection software. The software offers a measure of automation, checking student work against hundreds of millions of websites, papers, monographs and journal articles without much input from instructors already strapped for time.

“Most of the time people are using antiplagiarism products because their classes are so large they can’t read everything students are writing,” Schorn said.

Criticism against plagiarism detection software normally focuses on the opposite of Schorn’s findings: false positives. Some researchers have found the software is tuned to be too sensitive, flagging student use of jargon and common definitions as potential examples of unoriginal writing.

“‘False negatives’ are a sort of dog-bites-man twist on one usual critique of this software, though I’d rather have students slip through cracks than stand falsely accused,” said Douglas Hesse, professor of English and executive director of writing at the University of Denver. He described Schorn as a “thoughtful and careful scholar” who had produced a “compelling” but “modest” study he would like to see replicated on a larger scale.

Susan M. Lang, professor of rhetoric and technical communication and director of first-year writing at Texas Tech, said she was not surprised by Schorn’s results. Lang was part of a 2009 research team whose work raised several issues about Turnitin.

“Given the exponential explosion of information quantities on the 'net, as well as the constant shifting and reposting of content, the potential is always there for missed or inaccurate detection,” Lang said in an email. “However, one would think that in eight years, Turnitin would have been able to improve their performance with false negatives -- that doesn’t seem to be the case.”

The University of Applied Sciences for Engineering and Economics, also known as HTW Berlin, has perhaps the longest track record for studying the efficacy of plagiarism detection software. Researchers there have conducted six studies of products on the market since 2004. The most recent, from 2013, found no significant improvements from previous tests.

“Most troublesome is the continued presence of false negatives -- the software misses plagiarism that is present -- and above all false positives,” the introduction to the 2013 test reads. “So-called plagiarism detection software does not detect plagiarism. In general, it can only demonstrate text parallels. The decision as to whether a text is plagiarism or not must solely rest with the educator using the software: it is only a tool, not an absolute test.”

Turnitin received a score of 67 percent in that test, high enough to beat more than a dozen other products, but still low enough to be deemed only “partially useful” to instructors.

Schorn said she based her own tests on HTW Berlin’s research.

In addition to the issues of false negatives and positives, plagiarism detection software fits into a larger ethical debate about how to teach writing. Hesse, for example, called the software a “side issue” in that conversation.

“Students need to learn and experience writing as an activity by thoughtful people for thoughtful people, as a complex skill that develops over time, with diligence, often through fits and starts,” Hesse said. “Teachers need the skill and time to create authentic tasks and to coach student writers through them.”

In a position paper adopted in 2013, the National Council of Teachers of English said machine grading “compels teachers to ignore what is most important in writing instruction in order to teach what is least important.” Coupled with the rise in standardized testing, machine grading threatens to “erode the foundations of excellence in writing instruction,” the paper reads.

Schorn said the ethical debate has died down as the use of plagiarism detection software has increased.

“The real ethical question is how you can sell a product that doesn’t work to a business -- the sector of higher education -- that is really strapped for cash right now,” Schorn said. “We’re paying instructors less, we’re having larger class sizes, but we’re able to find money for this policing tool that doesn’t actually work. It’s just another measure of false security, like having people take off their shoes at the airport.”