You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

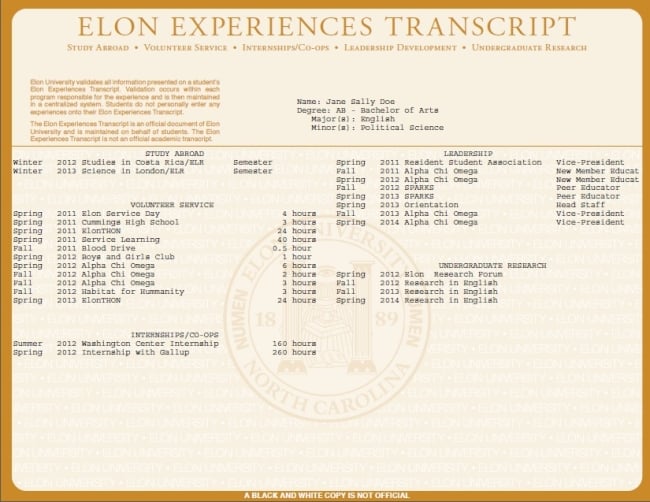

Elon University's experiences transcript

Elon University

Most people in higher education agree that the old-school college transcript fails to adequately capture what students learn and do during their time in college.

Student affairs administrators and college registrars often see the transcript’s shortcomings in their jobs. So the two national associations that represent those groups today announced a project to develop models for a more comprehensive student record.

“The outcomes of a college experience are more than a degree,” said Kevin Kruger, president of NASPA: Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education.

The Lumina Foundation has kicked in $1.27 million for NASPA to partner with the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers (AACRAO) to explore how to collect, document and distribute information about student learning and “competencies,” including what is gleaned outside of the traditional academic classroom.

While the field is nascent, said Mike Reilly, AACRAO’s executive director, it’s developing quickly. Reilly said the two associations hope to provide some guidance.

“There’s a lot of innovation taking place,” he said. “People are looking for examples right now.”

Student knowledge that might be documented in next-generation transcript prototypes include co-curricular or experiential learning -- maybe working on a campus robotics team -- or even soft skills like critical thinking and good communication. Digital badges also could be included.

The current approach to transcripts “only tells a fraction of the story,” said Cathy Sandeen, chancellor of the University of Wisconsin Colleges and Extension and a former vice president at the American Council on Education.

Sandeen welcomed the Lumina-funded project, saying that colleges need ways to “more granularly validate and acknowledge different components of learning.”

The two associations will tap eight colleges to develop and test several models of a “comprehensive student record.” They are avoiding the word “transcript,” Kruger said, because whatever emerges will be broader than a list of courses and grades.

The project’s leaders are accepting applications from colleges that want to participate. They plan to select institutions that represent higher education’s breadth. The range of participants will include community colleges, minority-serving institutions and research universities.

No single take on a student record will emerge from the process, said Kruger.

“We’re deliberately looking at a wide range of approaches,” he said. “This is not going to be a one-size-fits-all model.”

Yet the registrars and student affairs groups got involved in part to bring some standardization to the discussion.

For example, institutions like Elon University and Stanford University are considered by many to be pioneers in the field, having developed “extended” transcripts that include more than grades. Other colleges are getting into the game, often putting their own spin on transcripts.

Likewise, many colleges have created electronic portfolios to help students better explain their experience in college.

All the variation isn't a bad thing, Reilly and Kruger said. But it can create confusion on the receiving end.

For example, different colleges seek to transmit the information in different ways. Reilly joked that Stanford’s technical sophistication with distributing extended transcripts is akin to sending one by “telepathy.” Other colleges are more traditional. And employers have to make sense of it.

“If you have too many approaches,” said Kruger, “it’s hard for employers to know what’s valuable.”

Making Sense of Learning

The rise of competency-based education contributed to the project’s creation.

Academic programs based on competencies -- a student’s ability to demonstrate mastery of a learning goal -- can look different than a conventional grouping of courses into 120-credit degrees. That’s particularly true of direct-assessment programs, which do not rely on the credit-hour standard.

Some of the roughly 300 colleges that have created competency-based credentials, or are working on them, still “map” their transcripts to conventional course equivalents. That means someone could have their demonstrated -- and required -- competencies in quantitative skills translated into a three-credit gateway math course equivalency. Likewise, competencies in business essentials could map to a business 101 equivalency.

Others institutions, like Northern Arizona University, have created secondary, competency-based transcripts.

In either case, the registrars typically are the ones that get stuck with the brass tacks of converting competencies into the language of transcripts.

Reilly said traditional transcripts still have value, particularly for students who transfer to other institutions or apply to graduate school. “Academics generally know how to use that document,” he said.

A comprehensive digital learning record, however, which a student could update throughout a lifetime, is a different animal. That approach has plenty of potential in the knowledge economy, said Reilly. He pointed to diploma supplements in the United Kingdom as an early example.

“This could really become the coin of the realm,” Reilly said.

A separate Lumina-funded project, announced last week, will seek to create a web-based "credential registry." Researchers at George Washington University and Southern Illinois University at Carbondale will contribute to the registry, which is intended help users compare the quality and value of credentials, including college degrees and industry certifications.

Lumina also is pulling together a large number of higher education and other groups to create a shared language and a common framework for credentials.

Several vendors and nonprofits have done extensive work with digital repositories for student knowledge. Notable players include Parchment, the National Student Clearinghouse and Campus Labs. Related offerings include those from Merit Pages, Degreed and the Mozilla Foundation’s Open Badges.

The new transcript project will tap some of those groups’ expertise, Kruger said. Likewise, the work will draw heavily from the Degree Qualifications Profile (DQP), a Lumina-supported framework that seeks to determine what students should know and be able to do at the associate, bachelor’s and master’s degree levels. A revised version of the DQP emerged in draft form last year.

Reilly said faculty members will take a leadership role in working on the comprehensive transcript model from the eight participating institutions.

“We’re going to be insistent that there’s a faculty member represented,” he said.

The goal is to create tools for colleges to demonstrate and articulate student learning, said Kruger, as well as authenticating and verifying that knowledge. He hopes employers will use the new forms of transcripts. But even if they don’t take off in the job market, Kruger said, the academy should benefit from the effort to translate lifelong learning into a student record.

Amy Laitinen, deputy director of New America’s higher education program, applauded the project. Laitinen, a former White House and U.S. Education Department official who has criticized the credit-hour standard, said the new effort shows that mainstream higher education is getting more serious about the use of competencies and learning outcomes.

“Change is here,” she said. “It’s happening.”