You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

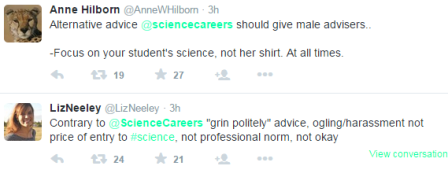

One of the many tweets about AAAS's retracted advice column.

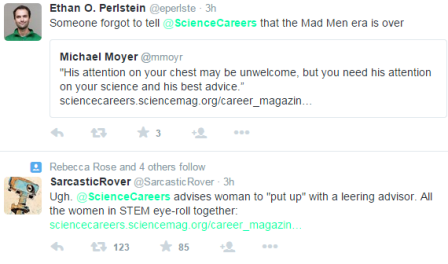

“His attention on your chest may be unwelcome, but you need his attention on your science and his best advice.”

With those words, Alice S. Huang, a senior faculty associate in biology at California Institute of Technology known for her pioneering research in molecular animal virology, and a regular columnist for Science, launched a wave of criticism Monday that resulted in the disappearance and subsequent retraction of her advice piece. Questions about the journal’s editorial process also linger, along with commentary on what some have described as a “one step forward, two steps back” path to gender equity in the sciences.

Huang, meanwhile, says she wrote her column with the best long-term interest of the person seeking help in mind, and that she hopes to address the controversy in a future column.

Here’s how it started. Huang, a former president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science who offers regular career advice to young scientists on AAAS’s Science Careers website, received the following query:

Dear Alice,

I just joined a new lab for my second postdoc. It’s a good lab. I’m happy with my project. I think it could really lead to some good results. My adviser is a good scientist, and he seems like a nice guy. Here’s the problem: whenever we meet in his office, I catch him trying to look down my shirt. Not that this matters, but he’s married. What should I do?

-- Bothered

Huang responded as follows:

Imagine what life would be like if there were no individuals of the opposite -- or preferred -- sex. It would be pretty dull, eh? Well, like it or not, the workplace is a part of life.

It’s true that, in principle, we’re all supposed to be asexual while working. But the kind of behavior you mention is common in the workplace. Once, a friend told me that he was so distracted by an attractive visiting professor that he could not concentrate on a word of her seminar. Your adviser may not even be aware of what he is doing.

Huang then offered a primer (with the disclaimer that she is not a lawyer) on the legal implications of the adviser’s behavior, saying that it didn’t appear to be unlawful:

Some definitions of sexual harassment do include inappropriate looking or staring, especially when it’s repeated to the point where the workplace becomes inhospitable. Has it reached that point? I don’t mean to suggest that leering is appropriate workplace behavior -- it isn’t -- but it is human and up to a point, I think, forgivable. Certainly there are worse things, including the unlawful behaviors described by the [Equal Employment Opportunity Commission]. No one should ever use a position of authority to take sexual advantage of another.

Ultimately, Huang said the postdoc should probably “put up with” the behavior in “good humor:”

As long as your adviser does not move on to other advances, I suggest you put up with it, with good humor if you can. Just make sure that he is listening to you and your ideas, taking in the results you are presenting, and taking your science seriously. His attention on your chest may be unwelcome, but you need his attention on your science and his best advice.

Readers began to criticize the post almost immediately on social media, accusing it of casual treatment of a behavior that some would call sexual harassment. @NIH_Bear tweeted, for example, that it was “painful to have to say, but ‘probably not illegal’ and ‘acceptable in the workplace’ are not even close to the same thing.” @lexbwebb said, “You can’t be serious @ScienceCareers. This is seriously unfortunate. #EverydaySexism passed off as career advice?!” There were references to jaws dropping, along with Huang’s status as a senior leader among scientists -- which some commenters said gave her words extra weight.

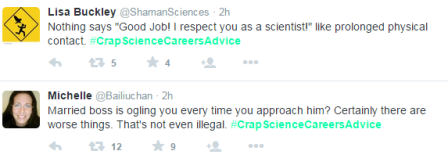

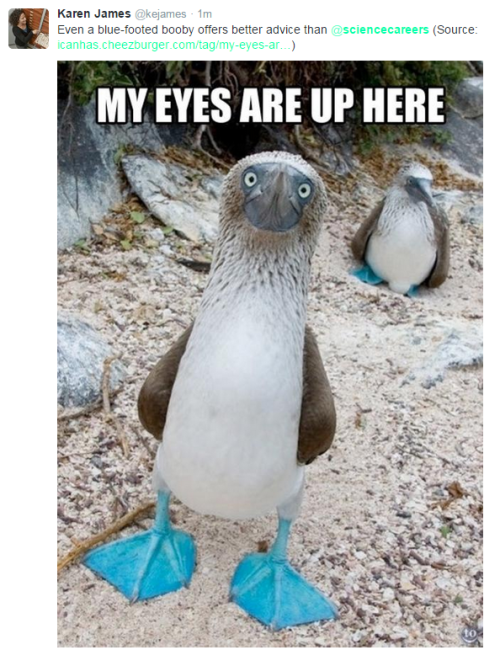

Here are some other reactions:

Soon a critical post appeared on the feminist blog Jezebel, which is part of Gawker, under the admittedly sensationalist but not inaccurate headline, “Science Advice Columnist: Just Let Your Adviser Stare at Your Tits.”

Huang’s column also inspired several grimly humorous hashtags, such as #CrapScienceCareersAdvice. A few contributions:

Within hours, Science removed the post, at first offering no explanation. A few hours later, an editor’s note appeared, saying the article had been removed because it did “not meet our editorial standards, was inconsistent with our extensive institutional efforts to promote the role of women in science and had not been reviewed by experts knowledgeable about laws regarding sexual harassment in the workplace.”

The note said Science “regretted” that the article had not undergone “proper editorial review prior to posting” and that women “in science, or any other field, should never be expected to tolerate unwanted sexual attention in the workplace.”

Science’s response met with some criticism, with some saying that the post should have been preserved for the purpose of dialogue and transparency. (A cached version is available here.) The retraction watchdog site Retraction Watch also took note. A spokeswoman for Science said the publication worked to offer a swift apology once it was alerted to the post’s content, and that it’s looking into how it was published in the first place.

In an interview, Huang said she was aware of the backlash, and regretted putting Science or the AAAS in any kind of negative light. Advice columnists by definition own their opinions, she said, taking full responsibility for her piece.

Huang, who is 76, said she’d witnessed, either directly or indirectly, just about “every” kind of sexism that exists in the sciences, and that harassment is a serious offense that can greatly impact a young scientist’s life. But she said the legal definition of harassment was in her view the best way to define it in her column, and that the behavior described didn’t appear to meet that threshold.

“In the column there isn’t a large amount of space to go into great detail about the issue and one has to think of what is the best advice that is realistic under the circumstances,” she said. At the same time, Huang said she understood that “the individual will draw their own line as to where they fall in being able to put up with a certain degree of sexual harassment, and not everyone will take my stance on it.”

In addition to lots of criticism, Huang said she’d received some “helpful” responses from readers Monday about alternative ways to handle an adviser’s uncomfortable behavior. She said she hoped to offer some of those ideas in a future weekly column. “There’s no reason they shouldn’t be published. I want to give credit to those who have given this some thought.”

Ultimately, Huang said, “What I try to do is give advice from experience, and to give the advice that would serve the writer well into the long-term future. I’m taking their best interests to heart rather than being in one camp or another camp or trying to push my own political agendas.”

Kathryn B. H. Clancy, an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, co-wrote a popular 2014 paper about the prevalence of sexual harassment at science field sites. She said she thought Huang’s advice bothered many people because it’s simply “bad advice.”

“If your adviser is openly leering at you, I don’t understand how it follows that blithely ignoring that will lead to a good advising relationship and good science,” she said. “If he is objectifying you, I can hardly expect him to set that aside when it’s time to review manuscripts, or sponsor you at the next conference, or write you a good letter of reference for your next position.”

Jessica Polka, a postdoctoral fellow in systems biology at Harvard University, was slightly more sympathetic, but also said she thought Huang’s advice was poor.

Polka said she thought she understood where Huang was “coming from,” in that graduate students and postdocs are “vulnerable.” In many cases, Polka said, “their entire career hinges on the subtleties in the tone their adviser takes in recommending them.” So it makes sense that the situation should be dealt with “diplomatically,” she said -- but not “ignored.”

“This advice perpetuates a culture of harassment and I'm shocked that it was published,” she said, crediting Science Careers with acknowledging what she called its “error.”

So what would have been better advice?

Katie Hinde, an assistant professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard who co-wrote the 2014 paper with Clancy, recommended “systematically and unequivocally” repudiating the adviser’s behavior. Beyond that, she said, Huang could have offered a much more holistic discussion about sexual harassment, to include not only the legal definition offered by the EEOC but also Title IX of the Educational Amendments of 1972, as well as policy statements from professional societies and institution-specific principles and codes of conduct.

Clancy said the initial error was perhaps leaving such a complex advice topic to someone outside the legal profession, or, more generally, someone writing an advice column, since it implied that the postdoc had control over the situation. But lots of scientists have offered their own opinions on social media and secondary websites, including on PubChase. Here’s what Polka wrote:

Bothered's question makes it clear that this behavior is unwanted and recurrent. What is not clear is whether the adviser is aware his behavior is disturbing (or even noticed). While “good humor” should not be used to silently tolerate leering, it could be employed to call attention to the behavior nonverbally (with a sharp clearing of the throat, for example). If this gentle approach fails, Bothered should follow with a verbal request for eye contact. Failing this, she should not hesitate to communicate clearly that the alternative makes her uncomfortable. If he truly has no regard for the professional environment he is creating, a third party (such as a university ombudsperson) should be involved.

John Borghi, a cognitive neuroscientist at Rockefeller University and one of those who publicly criticized Science for taking down Huang's post, said via email he would have a preferred a similar conversation to happen at the site of the article.

“As a hugely influential supporter of science advocacy and science communication, AAAS was in a position to provide a forum for a very difficult but very necessary conversation about harassment within the complex hierarchies of power that exist in science,” he said. “By removing the post, first with no explanation and then with a very unsatisfying editor’s note, AAAS gives the perception that they would prefer if such conversations occurred elsewhere.”