You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Education Commission of the States

WASHINGTON -- Get a group of higher education wonks in the same room talking about public funding and they're bound to discuss how flattening and declining state investment is hurting students and colleges alike.

But while a group of experts acknowledged this fact during a forum at the National Press Club on Wednesday, the main discussion centered around not only a lack of money but a lack of vision in the implementation of state-awarded grant programs.

Experts and authors of a report, “Redesigning State Financial Aid,” released Wednesday by the nonpartisan Education Commission of the States (ECS), contend state grant programs should better meet the needs of modern students, who have access to a growing number of pathways to higher education.

“The era for when many of these programs were formed [was] very different” from today's higher education landscape, said Carol D’Amico, an executive vice president at USA Funds, a nonprofit student loan guarantor and scholarship provider that collaborated with ECS on the report.

By overhauling aid programs, authors and experts claim, states -- which in 2013 awarded $11.2 billion in student aid to 4.5 million students -- can boost nontraditional students' access to aid money and potentially improve their postsecondary education success rates.

In 2012 states spent $1,420 in grant aid per student, covering about 16 percent of public college tuition, which that year averaged $8,800.

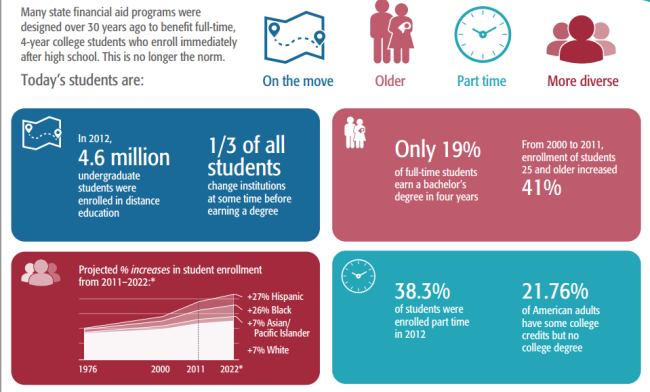

State aid programs were developed with a focus on traditional college students -- young adults who enroll right after high school and are between 18 and 24 -- but the report's authors note that today's college students are a much more diverse set then several decades ago, and often learn in less traditional ways than in the classroom at a four-year institution.

They highlight a bevy of statistics: 4.6 million undergraduate students were enrolled in distance education in 2012; one-third of all students transfer institutions before earning their degrees; from 2001 to 2011, the enrollment of students 25 and older increased 41 percent; nearly 22 percent of American adults have some college education but no degree; 38 percent of college students were enrolled part time in 2012; and, perhaps most telling of all, only 19 percent of full-time undergraduates earned a bachelor's degree in four years.

Despite these statistics, ECS researchers found that of the 100 largest state-funded financial aid programs in the U.S., 29 only funded students who enrolled full time and 43 limited the number of years a student can receive a grant, a restriction not conducive to part-time students who take several years longer to graduate than do their full-time peers.

Another statistic: 33 programs link aid eligibility to standardized test scores and grade point averages, measures that, according to the report, “are of little relevance” to adults already in the marketplace.

During Wednesday's forum, experts explored the possibility of linking state aid to student performance while in college, or finding ways to encourage part-time students to take more credits and thus increase the likelihood for completion. One thought was to offer grants to all students, but increase them in proportion to the number of credits a student takes.

“Just giving money to those students is not enough,” Sandy Baum, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute, said of nontraditional students. “It's more about providing incentive and support than it is about just rewarding people.”

The report offers a number of suggestions beyond expanding the pool of students eligible for grants. It suggests that states make students aware of their grant award as early as possible, even before they enroll in an institution. It also suggests that aid not be tied to academic semesters or quarters, but that it be available for students in programs with alternative enrollment schedules.

Authors call for grant aid to be student centered, rather than institution centered.

“Program design decisions [should be] predicated by how states can utilize financial aid programs to support student access and success first, rather than employing student aid as a conduit of institutional support,” the report says.

Flattening and declining state investment has caused many public universities and community colleges to raise tuition. It's this fact, panelists said Wednesday, that makes it imperative for nontraditional students to have access to grant funds.

ECS is still in the early stages of a longer-term project to overhaul state grant programs. It's in the process of compiling a database of state aid programs and hopes to consult with states individually about overhauling outdated programs.