You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

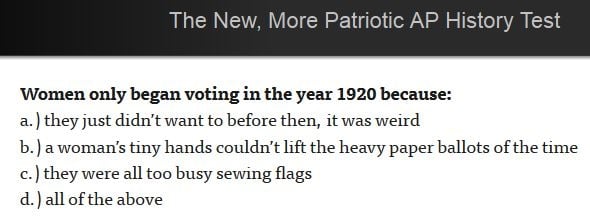

New questions for the AP U.S. History exam, as imagined by the comedy Web site Funny or Die.

Funnyordie.com

American history is constantly debated not only by historians but by politicians. So it was largely unsurprising when some Republicans started to criticize the new Advanced Placement U.S. history framework last year for allegedly downplaying positive elements of America’s past. Many historians were caught off guard last week, however, when the criticism grew legs, at least in Oklahoma: a legislative committee there easily passed a bill declaring the new AP curriculum an “emergency” threatening the “public peace, health and safety,” to be defunded in the coming school year.

Facing a wave of criticism, the bill’s sponsor, Rep. Daniel Fisher, said late last week that he was reworking the bill the make it less “ambiguous,” and that he was in fact “very supportive of the AP program" in general. (The current version of his bill states that funding will not be revoked if the state reverts back to the prior framework and exam.) Another legislator said the rewritten bill will ask Oklahoma’s Board of Education to review the new curriculum, instead of cutting funding, The Oklahoman reported.

Although the debate has gone farthest in Oklahoma, policy makers in Georgia, Texas, South Carolina, North Carolina and Colorado also have expressed opposition to the new curriculum, according to The Washington Post.

The Oklahoma bill’s future is unclear, and some aren’t taking it too seriously. It served as comedic fodder for the Web site Funny or Die, for example, which published a parody of a new AP history exam featuring questions such as: "Women only began voting in the year 1920 because: a.) they just didn’t want to before then, it was weird; b.) a woman’s tiny hands couldn’t lift the heavy paper ballots of the time; c.) they were all too busy sewing flags; d.) all of the above."

But the movement has historians concerned about the possible spread of legislative actions against the AP framework -- and the fate of what they say is a good test that encourages precisely the kind of historical thinking they want students to pick up on their way to college.

The debate on AP history will be discussed Friday on "This Week," Inside Higher Ed's free news podcast. Sign up here to be notified of new "This Week" podcasts.

“The big problem overall is this issue of people’s willingness to let teachers explore the complexities of history, to recognize that what you want students to learn is historical thinking, and to see the complexity that makes history more than a simple story,” said James Grossman, executive director of the American Historical Association. “That’s what revisionism is. It’s the only way the discipline changes over time, as it takes up new things and has new insights. And one of the ways that gets translated into high school classrooms is through the AP.”

David Wrobel, Merrick Chair of Western History at the University of Oklahoma, said there’s “universal” opposition to the bill among his colleagues and the many high school history teachers he works with through institutes and grants to promote “K-20” education within his state. Wrobel said he shared some of Grossman’s concerns, as well as practical ones about how high schools will scramble to create a new, college-level U.S. history program by fall if the bill is ultimately successful, and how it will adversely affect Oklahoma students competing for admission to college.

“You take a nationally recognized measure of excellence and student achievement away from students that are applying to colleges and universities across the country,” Wrobel said, “and students from the state of Oklahoma are obviously disadvantaged against those coming from institutions where they have had an opportunity to do AP U.S. history.”

Students also miss out on a course they think is valuable, he said, since AP U.S. history students in formal course evaluations “talk about what the course has meant to them, and the vast majority not only mention how it made them critical thinkers and enhanced their content knowledge, but how AP U.S. history also enhanced their understanding of what citizenship means.”

Criticism of the new curriculum, known as APUSH, and its publisher, the College Board, got going last year, with some conservatives saying that the test ignored important aspects of American history and cast it in too negative a light. In August, the Republican National Committee approved a resolution summarizing their concerns and asking state legislators to investigate the test and for Congress to “withhold any federal funding to the College Board (a private nongovernmental organization) until the APUSH course and examination have been rewritten in a transparent manner to accurately reflect U.S. history without a political bias and to respect the sovereignty of state standards, and until sample examinations are made available to educators, state and local officials[.]”

Among the Republican committee’s more specific concerns were that the framework “includes little or no discussion of the Founding Fathers, the principles of the Declaration of Independence, the religious influences on our nation’s history and many other critical topics that have always been part of the APUSH course” and that it “excludes discussion of the U.S. military (no battles, commanders or heroes) and omits many other individuals and events that greatly shaped our nation’s history (for example, Albert Einstein, Jonas Salk, George Washington Carver, Rosa Parks, Dr. Martin Luther King, Tuskegee Airmen, the Holocaust).”

In response to the criticism, the College Board released a practice exam for the new framework, hoping to reduce suspicions about the test. The questions suggest that, contrary to the Republican resolution, students will study the founding of the United States and the civil rights movement, but also will explore topics such as poverty in American life that are less triumphal than battle victories. In an open letter, David Coleman, College Board president, said he hoped the unprecedented move of releasing an exam to parties other than certified AP teachers would quell concerns that the framework neglected or misrepresented key elements of American history.

"People who are worried that AP U.S. history students will not need to study our nation's founders need only take one look at this exam to see that our founders are resonant throughout," Coleman said, noting that the framework was just that, and that local teachers could add to it as they saw fit.

But the move did little to alleviate tensions about the new test. Stanley Kurtz wrote in the National Review later that month that the framework was “closely tied to a movement of left-leaning historians that aims to ‘internationalize’ the teaching of American history. The goal is to ‘end American history as we have known it’ by substituting a more ‘transnational’ narrative for the traditional account.” His commentary is light on specific examples of problematic questions or concepts, but he wrote that the older, relatively short framework allowed "liberals, conservatives and anyone in between [to] teach U.S. history their way, and still see their students do well on the AP test." By contrast, he said, the "new and vastly more detailed guidelines can only be interpreted as an attempt to hijack the teaching of U.S. history on behalf of a leftist political and ideological perspective. The College Board has drastically eroded the freedom of states, school districts, teachers and parents to choose the history they teach their children."

In September, the curriculum was a hot topic at the Values Voter Summit in Washington. Ben Carson, a pediatric neurosurgeon and professor emeritus of medicine at Johns Hopkins University who has considered running for president, told audience members, “I think most people, when they finish that course, they’d be ready to sign up for ISIS,” or the so-called Islamic State, The Washington Post reported.

Grossman, of the American Historical Association, countered some of the talk in his own New York Times op-ed about the importance of revisionism in historians’ work -- however disquieting.

“Fewer and fewer college professors are teaching the [U.S.] history our grandparents learned -- memorizing a litany of names, dates and facts -- and this upsets some people,” Grossman wrote. “‘College-level work’ now requires attention to context, and change over time; includes greater use of primary sources; and reassesses traditional narratives. This is work that requires and builds empathy, an essential aspect of historical thinking.”

He added, “The educators and historians who worked on the new history framework were right to emphasize historical thinking as an essential aspect of civic culture. Their efforts deserve a spirited debate, one that is always open to revision, rather than ill-informed assumptions or political partisanship.”

The AP U.S. history exam always has emphasized critical thinking, differentiating it from some of the more rote curriculums mandated by some states. But whereas the old framework focused on the colonial period to about the 1980s, the new framework places a bigger emphasis on historical thinking and on the Americas from the 1490s to the 1600s and the U.S. after the Cold War, including 9/11 and the wars that followed.

In a statement addressing the Oklahoma controversy, the College Board said the framework and other AP materials were written by seasoned educators who sought to take “a more transparent and flexible approach, offering guidance to teachers on what might be in the exam while providing for alignment with local requirements and standards.” The statement also noted that Oklahoma students are on track to earn nearly $1 million in college credit this year through the exam -- another argument many opponents of the bill have raised.

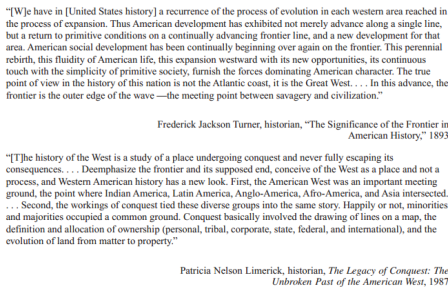

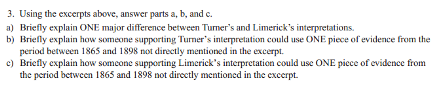

Grossman said it was his opinion that the new test reflected the advancement of historical study and a greater emphasis on historical thinking -- a good thing -- but that it wasn’t radically or ideologically different from the last. He pointed to a sample essay question, for example, that presents two very different views of Manifest Destiny, the philosophy of westward expansion, and asks students to compare them. The test doesn’t suggest that one is better or more accurate than the other, however, he said.

Ben Keppel, an associate professor of American history at the University of Oklahoma, said he thought the bill “was a really horrible idea and a misunderstanding of what history is and what history teachers do.”

The new framework, he said, “is a modern curriculum” that asks students to think critically about different pieces of evidence and different perspectives. Without such richness of texts, he said, “that’s not intellectual history, that’s not education, that’s a kind of ideological indoctrination.” Like Wrobel, he guessed that his department, if polled, would demonstrate a “rare” show of unanimity of opinion against the legislation.

It’s unclear from Fisher’s bill exactly what constitutes an emergent threat to the public in the new framework. He did not return a request for comment. But Wrobel said many of his public statements and those of other critics touched on the concept of American exceptionalism.

Wrobel, who has written several books on the topic, said he disagreed strongly with the way the term was being used as a kind of “political football” or “litmus test” for one’s political affiliation. The actual concept of American exceptionalism, which has been the subject of rich scholarship for centuries, really means that the U.S. “has faced a whole series of incredibly complicated challenges and nonetheless managed to develop into a largely functional, multicultural democracy,” he said. Wrobel added that it was unfair that AP U.S. history was being “saddled” with an “unsubtle” debate, and that he “would love for people not to be drawn into sound bites or easy assumptions about a curriculum, but to get to talk with students and teachers about what incredibly thoughtful, smart students we are seeing develop from programs that push them intellectually.”

The College Board’s statement also addressed the American exceptionalism debate, which it said has been “marred by misinformation.”

“The redesigned AP U.S. History course framework includes many inspiring examples of American exceptionalism,” the board said. “Rather than reducing the role of the founders, the new framework places more focus on their writings and their essential role in our nation's history, and recognizes American heroism, courage and innovation.”

It continues: “Because this is a college-level course, students must also examine how Americans have addressed challenging situations like slavery. Neither the AP program, nor the thousands of American colleges and universities that award credit for AP U.S. history exams, will allow the censorship of such topics, which can and should be taught in a way that inspires students with confidence in America’s commitment to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

Grossman said he didn’t think the debate was going away any time soon, given the unique “accessibility” of history.

“History has an unusual combination of being politically sensitive and also a discipline that more people feel they know more about than some other disciplines,” he said, noting it would be “hard to imagine” a state legislature mandating what a chemistry teacher should be teaching, for example. “Historians have been successful writing for the general public and many people have a deep and abiding interest in history, and that’s a wonderful thing. But there are going to be more legislators who feel they are qualified in this area.”